After what felt like the UK’s longest winter, Marcus Bernard and I met on one of the hottest recorded days of 2023 at Peckham Skylight, my personal favourite for summer hangouts. I was excited; Marcus and I have worked together before, but never one on one. A producer with integrity, vision, and dreams of creativity free from commodity, I’m always left feeling curious, warm and stretched after our conversations – and this one was no different.

I sat down with Marcus to chat about his most recent produced play: Dismissed, written by Daniel Rusteau. It tells the story of a school teacher trying to save one of her pupils from expulsion and aims to highlight class and racism in the state education system.

School exclusion is a topic very close to my heart. I’ve had friends, family and old school friends failed by the system and know how hard it is to make it out once excluded, if you ever can.

Growing up, it was a concept that never sat well with me. How can you give up on children? What was exclusion actually teaching them? What happens to the rest of us knowing that the seat at the back of the classroom will remain empty for the rest of our years at school – did schools ever think about that?

Knowing these people more intimately than a school quick to get rid of them for fear of lowered funding and league table ranks, I was privy to what was really going on in their lives: loss, growing pains, unsettled home lives, poverty and trauma. These were experiences which are rarely meaningfully acknowledged in the school system.

Marcus had a similar perspective. He’s open about the fact that, growing up, he felt like he had nowhere to belong. He remembers being in a lot of fights which led to him becoming a child of exclusion himself.

“I felt lost and I didn’t have an outlet to express that,” he recalls. What his school didn’t see was a child figuring himself out in the midst of difficult family beginnings. For so many children across the UK, exclusion leaves out the experiences in young people’s lives that leads them to that point. It leaves out the care or work responsibilities placed on the child; the lack of parent-child time due to work; the lack of hobbies, creative outlets and money. It leaves out young people not eating well or sleeping well; the young people forced to grow up older than their years in order to step up to the realities around them.

What does punishment do to us?

As my politics grew, that feeling of exclusions never sitting well with me found its home in abolitionist praxis. That feeling then began to sit within understanding the systems of harm that create conditions of harm and lack. It dictates disposability in a world that should be built around no one being disposable. It means children, especially Black children, are constantly at risk of losing their chance at life well before it’s even started. This is what young people are up against in our schools and society today.

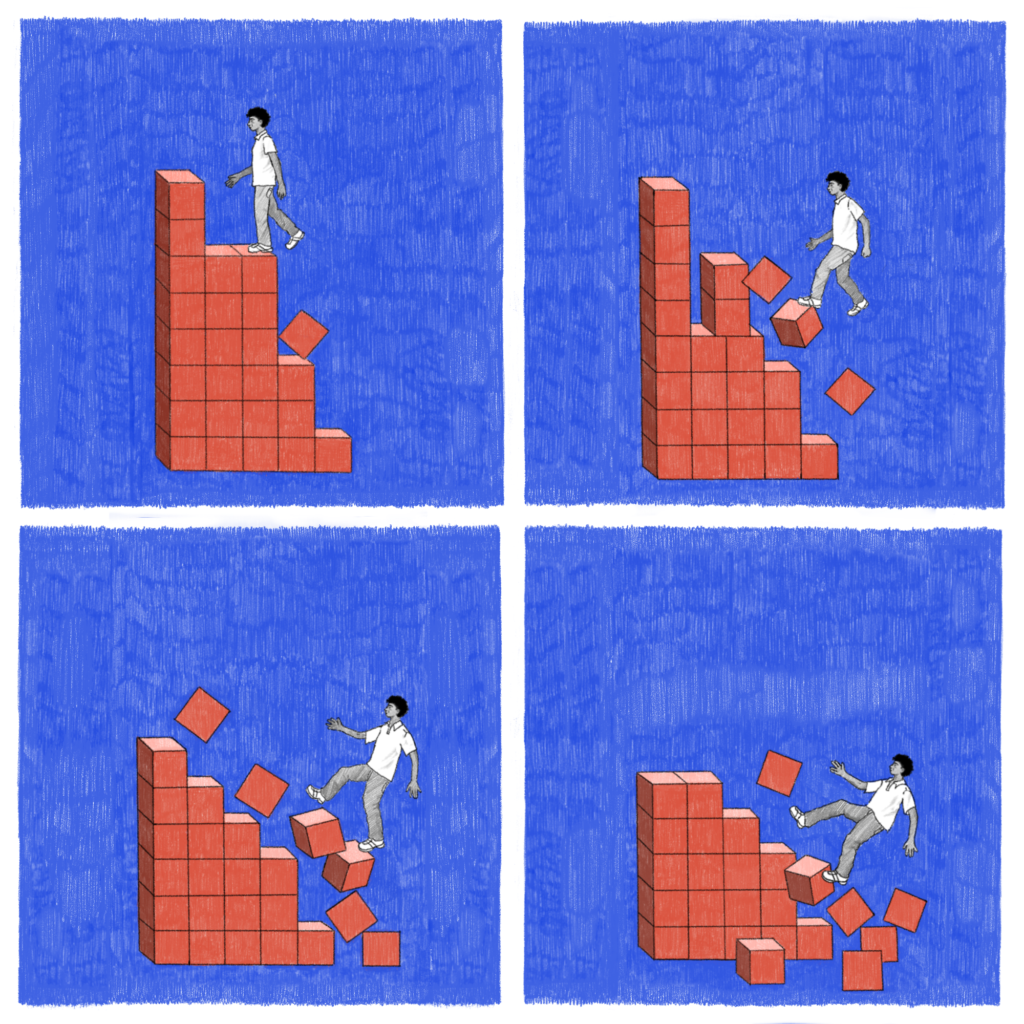

Simply put, Marcus doesn’t believe that exclusion works for its intended purpose of punishment, because “it doesn’t address the issues, it just displaces them.” He speaks more about once a child is excluded, they’re essentially put out and the school no longer needs to deal with them. without the structure and duty of care the school provides, It’s for whoever to deal with. Marcus questions what that instils in a child. He says “exclusions produce and reinforce feelings of abandonment, rejection and distrust in young people, as well as being unforgivable and worthy of being given up on- which are all damaging for self esteem and worth.”

“We are living in a society that washes its hands of the problem,” Marcus says – and this leaves only the problem to look after itself. This is where we find excluded young people more likely to be groomed within gangs, exposed to higher levels of violence, less likely to access the care and support needed to grow into adapted teenagers and young adults. “In many cases, the problem is actually made worse,” he concludes.

Marcus explains that compounding systemic issues of poverty, racism, policing, border and state violence are often the cause of the problems in the first place. When we look at the statistics, Black children are two times more likely than white children to be excluded; in some areas this goes as high as 5x more likely.

Along with this, other marginalised communities like disabled children, children from Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities and South Asian children (particularly from Pakistani and Bangladeshi backgrounds) also face higher than average rates of exclusion. When you expel young people, it gives little care for the lack of support system the child currently has.

In fact, research has shown that it is more likely for a child who has been expelled to live in inadequate or overcrowded housing, come from a low income background, is neurodivergent, has less support from the elders in their life due to them constantly having to work and more issues of the like. These compounding issues already mean the child’s needs are not being met and rather than seeing the problem stemming from systemic issues, it’s easier to place entire blame on the individual behaviour of the child who is merely reacting to these ongoing, unresolved issues of neglect.

Exclusions not only expose the state and education systems’ shortcomings with dealing with systemic issues, but also the flaws in our approach to raising children in society and what building blocks we instil in children to make them obedient adults – fear and punishment.

When your first life lesson is punitive, how does that shape how you view the world?

Marcus speaks about exclusions instilling fear and paranoia in him. “It made it harder for me to ask for help, to question, to be curious,” he says. ”Ultimately, I just learned to follow rules unquestioned.” Like so many other children, those who are excluded and those who are not, fear makes us rigid.

Fear coerces us into ‘good behaviour’ for fear of reprimand. That coercion signifies unequal power between us as people and the state and education system. It means we act accordingly not because we are encouraged to be ‘good people’ in our own right, but because not doing so leads to school exclusion, social and economic exclusion, and the denial of necessities and support. This coercion signifies these institutions can, and do, wield their power unreasonably – and they can do that against anyone.

School to prison pipeline

This power is disproportionately waged on working class and/or Black and brown youth within the schooling system. In the play, the protagonist Ashley brings up the school system being institutionally racist and highlights that Black children, especially Black boys, disproportionately face the brunt of that. Black children are criminalised from a young age and this process is formalised in the ‘school to prison’ pipeline.

Marcus describes this as “the clear pathway disadvantaged children go on to incarceration.” It starts with permanent exclusions to Pupil Referral Units (which have a disproportionate amount of Black children in) to the criminal justice system and prisons. He explains, “once you are excluded, your likelihood of this being your path increases dramatically”. Other state backed programs of criminalisation include PREVENT, which primarily target Black, brown and Muslim children.

This pipeline does nothing to address the behaviour or the child, nor the reasons behind it. Rather, it turns school staff into cops and informants of the state, forced to comply with these state programmes of surveillance and punishment or they too are at risk of punishment. This pipeline makes money for private prisons and the state at the expense of vulnerable young people, who are consequently robbed of the educational opportunities and life chances to which they are entitled.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

It then becomes clear how institutional racism, classism, islamophobia and ableism in our education system both creates and perpetuates harm in schools and wider society.

What would an education system based on care and not punishment look like?

For me, this reality makes the case for abolishing exclusions in education more apparent. If exclusions allow us to discard and disappear a problem, what would we do if this was no longer an option?

That requires us to think of better ways to support all children in the class. In the play, the protagonist teacher describes how Switzerland tackled their heroin epidemic by making heroin legal, having drug centres and and supporting drug users to use safely – which brought a huge decline to opioid deaths and rates of HIV.

I particularly loved this part of the play because she challenges the other teachers to think: what is a school really for? Is it for punishment, or rather a space to nurture the minds and wellbeing of young people? In our conversation, I ask Marcus what he thinks an education system based on care would look like.

He believes it’s two pronged. “Because children and school are not separate from society, we’d need to also fix systemic problems in society too,” he asserts. Within schools, that would look like well paid, resourced and supported teachers who are able to take the time to teach and be more active with how young people are doing. It would look like smaller classes so children get the care and attention needed to nurture their minds and wellbeing without there being a huge strain on the teacher. Marcus vividly paints this picture. “It would look like schools wanting to develop children not just for the world of work and labour, but to make well-rounded and happy human beings who are curious, empowered and know they are worthy of love and care.”

If this was the case, young people would read well, be socialised well and learn to be creative problem solvers. It wouldn’t be a churning system of working to pass exams and then becoming workers of the world, it would inspire young people to explore, to critique and to play more. From the outside it would mean: secure affordable housing, support for parents/carers, access to good healthcare, higher wages, access to healthy local foods, play areas, youth centres, and a restructuring of society that allows for people, not just parents to step in and communally watch out for children. He concludes “It means investing in harm prevention at its roots, and dealing with causes and structures of violence, not symptoms.”

I loved hearing about Marcus’s critiques of the system and his dreams of revolution. For me, our conversation affirmed that transforming this system starts with the understanding that none of us are disposable, despite a system that desperately tries to prove and act like we are.

We should not accept this as a necessary step for a better society. Rather, our focus on schools as a microcosm of society should spur us to want everyone in the classroom and society to enjoy the fruits of our collective care. If exclusion is retribution, abolition in education is freedom!

Abolishing exclusions is a necessary step to changing our schooling system and we know there are incredible organisations, podcasts and resources doing incredible work already, so I wanted to end by asking Marcus who his educators and influences are in this work.

He specifically wanted to highlight:

- Abolitionist futures

- Kids of Colour

- No More Exclusions all for their groundbreaking and radical work around abolition in schools and abolition as praxis.

For podcasts, he names:

For resources, he particularly names: