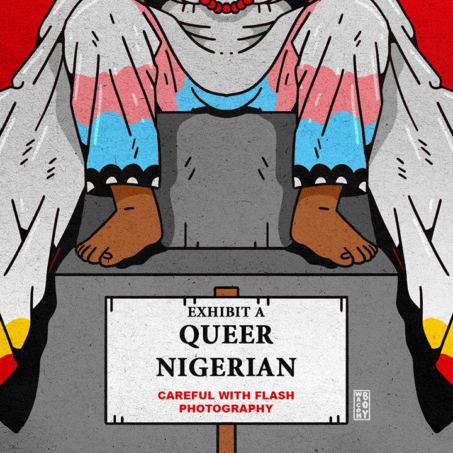

Over the past 3 years, 70% of all asylum claims for LBGTQ+ people have been refused in the U.K. This statistic is not surprising in itself, given the Conservative government’s hostile environment. However, when it is taken into account that over two thirds of these refusals were overturned on appeal, a concerning pattern comes to light. Of most of these appeals, judges overturned refusal decisions because those involved where wrongly applying the standard of proof required by law. The concept of the standard of proof relates to the extent to which the judge believes the person’s claim. Concerning asylum claims based on sexuality, claimants face undue difficulties making judges believe their claim, due to judges applying a higher standard than necessary, and rejecting claims where they should be accepted. This article will demonstrate the problems with the current approach of the courts towards these claims, and then examine the current policy in the matter.

The rule of the standard of proof revolves around the credibility of the claim for asylum. When making a decision, a judge must grant the application if there is a ‘reasonable degree of likelihood’ – or a 1 in 10 chance – that the individual is being persecuted on the basis of their sexual orientation in the country they are fleeing from (Asylum Policy Instruction: Sexual Orientation in asylum cases, Home Office, 2016, p. 22).

An analysis of this concerning pattern has brought two main issues to light. Firstly, handling such cases in the same way as other types of asylum claims overlooks the particularities of sexuality claims, meaning law and procedure is not sufficiently adapted to their specific nature. In addition, harmful preconceptions about sexuality are influencing decision making, impeding objective judgement of the facts and the law’s response to them. Due to these mistakes, judges are refusing claims because they don’t believe them, when all that is required is that they ‘accept’ the claimant’s account (Asylum Policy Instruction: Assessing credibility and refugee status, 2015, p. 12).

The particularity of sexuality claims:

In contrast to claims relating to other aspects of identity such as ethnicity or religion, claims relating to sexuality are particular in themselves, and an adaptive approach is required when gathering and evaluating all the information present.

The key to success of any asylum claim is proof of risk of persecution. In most cases, an individual can prove how they are personally at risk of violence, due to objective evidence relating to religion or ethnicity. However, with sexuality cases, the absence of proof is the proof itself: the fact that a person had to hide their sexuality, at all costs, is the very proof of the risk. Admittedly, the easiest way to establish a risk of violent consequences with no evidence of their cause, but it should not be the only way. It seems that unless the evidence portrays a person openly expressed their sexuality – risking their lives in doing so – their claims will not succeed.

During the interview process, an individual must state the reason for their claim, and identify why their life in particular is at risk. On the one hand, an individual may not find many difficulties in expressing their ethnic or religious identity at the root of their persecution. On the other hand, however, when it comes to LGBTQI+ claimants, feelings of shame or denial can make it exceedingly difficult to openly express sexuality, even in the most important time to do so. If a person cannot automatically and convincingly self-identify as LGBTQI+ before the end of a single 3-hour interview, they could have their claim denied.

The effect of prejudice on the analysis of evidence:

There exist many preconceptions and harmful stereotypes around sexuality, which cloud decision makers’ judgement and prevent them from accurately assessing evidence.

Due to a lack of understanding of sexuality, people often develop their own conceptions, leading them to extrapolate objective conclusions from personal opinion. Often, arbitrary ages are fixed as to the ‘correct’ age a person should ‘find out’ about their sexuality – but this age, being entirely based on preconception, varies from person to person. For example, when a person realises at primary school that they are queer, they are deemed ‘too young to know’, while at the same time a person who didn’t realise until they were an adult, ‘would have known sooner’ (McClellan & Cohen, 2017). Based on this discretionary system, a person who discovered their sexuality at the wrong age could have their claim refused.

Another element of prejudice against the LGBTQI+ community is in the discrediting of women’s bisexuality, particularly when she has any heterosexual relationships. For example, a queer woman who had been married to a man could not really be bisexual, otherwise she never would have had his children. This kind of preconception overlooks three possibilities: she could have used the relationship to hide her sexuality, or, for the same reason, have been forced into it, or she could actually be bisexual. A woman who identifies as bisexual, but has evidence of both ends of her attraction will unlikely be believed.

How can the system be improved?

It must be noted that each of the situations raised above has been explicitly anticipated by the Home Office asylum policy instruction on sexual orientation. Firstly, the instruction asserts that ‘extrinsic supporting evidence is not a prerequisite for a genuine claim’, thus, a claim cannot be refused for lack of objective proof (Asylum Policy Instruction: Sexual Orientation in asylum cases, Home Office, p. 23). Furthermore, interviewers are to identify and respond to difficulties such as ‘shame, secrecy, and painful disclosure’ (p. 13), to be receptive to indications other than a person directly ‘coming out’. Secondly, it is stated that ‘perceptions (of sexuality) may begin in childhood’ (p. 26), so a person cannot be too young to be queer, and at the same time, ‘what is relevant is current identity’ (p. 25), so a person can’t be too old to find out. If ‘evidence of opposite-sex relationships or parenthood must not be taken as evidence of a lack of credibility’ (p. 24), a person should not be labelled as ‘not fully gay’.

As a general rule of procedure, it is expected of each individual in the asylum claim process to be aware of their own prejudices and views, and avoid them influencing their professional conduct. Here, while prejudice can result from a general misunderstanding or actual preconceptions relating to sexuality, a person must rely fully on the guidelines provided by the Home Office. In addition, the principle of ‘shared responsibility’ establishes the cooperative nature of the process, meaning that the interviewer or lawyer must also make efforts in order to obtain, explore, and assess the relevant information (Asylum Interviews, Home Office, 2019, p. 24).

Here, it is clear that the Home Office policy provides all the guidelines necessary to accurately apply the low standard of proof, but in order to do so, the people involved must follow them. If the Home Office and lower courts simply followed their own guide, initial decisions would not be overturned, and people deserving of protection would be granted it sooner, rather than so much later.

Of course, the need for improvement throughout the entire process remains, through mechanisms such as specialised training, or intervention from LGBTQI+ rights organisations – but while the policy guidelines are there in writing, it wouldn’t hurt to use them.

Bibliography

1.Burton-Bradley (2017) ‘Not gay enough: the bizarre hoops asylum seekers have to leap through’; Available at https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/not-gay-enough-the-bizarre-hoops-asylum-seekers-have-to-leap-through-20171128-gzu1vq.html

2.Chapman (2019) ‘How the Home Office is failing LGBT+ applicants’; Available at https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/news/blog/how-the-home-office-is-failing-lgbt-applicants/

3.Keddie (2014) ‘Gay Russians attempt to take refuge in the UK’; Available at https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2014/02/gay-russians-attempt-take-refuge-uk-2014224135632859201.html

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

4.McClellan, Cohen (2017) ‘Why Gay Asylum Seekers Aren’t Believed’; Available at https://www.ein.org.uk/blog/why-gay-asylum-seekers-arent-believed

5.Bennet (2015) ‘What does an asylum seeker have to do to prove their sexuality?’; Available at https://theconversation.com/what-does-an-asylum-seeker-have-to-do-to-prove-their-sexuality-38407

6.Asylum Policy Instruction Sexual orientation in asylum claims Version 6.0, Home Office; Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/543882/Sexual-orientation-in-asylum-claims-v6.pdf#page=12&zoom=100,0,97

7.Asylum Policy Instruction Assessing credibility and refugee status Version 9.0, Home Office; Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/397778/ASSESSING_CREDIBILITY_AND_REFUGEE_STATUS_V9_0.pdf

8.Asylum Interview Version 7.0, Home Office; Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/807031/asylum-interviews-v7.0ext.pdf