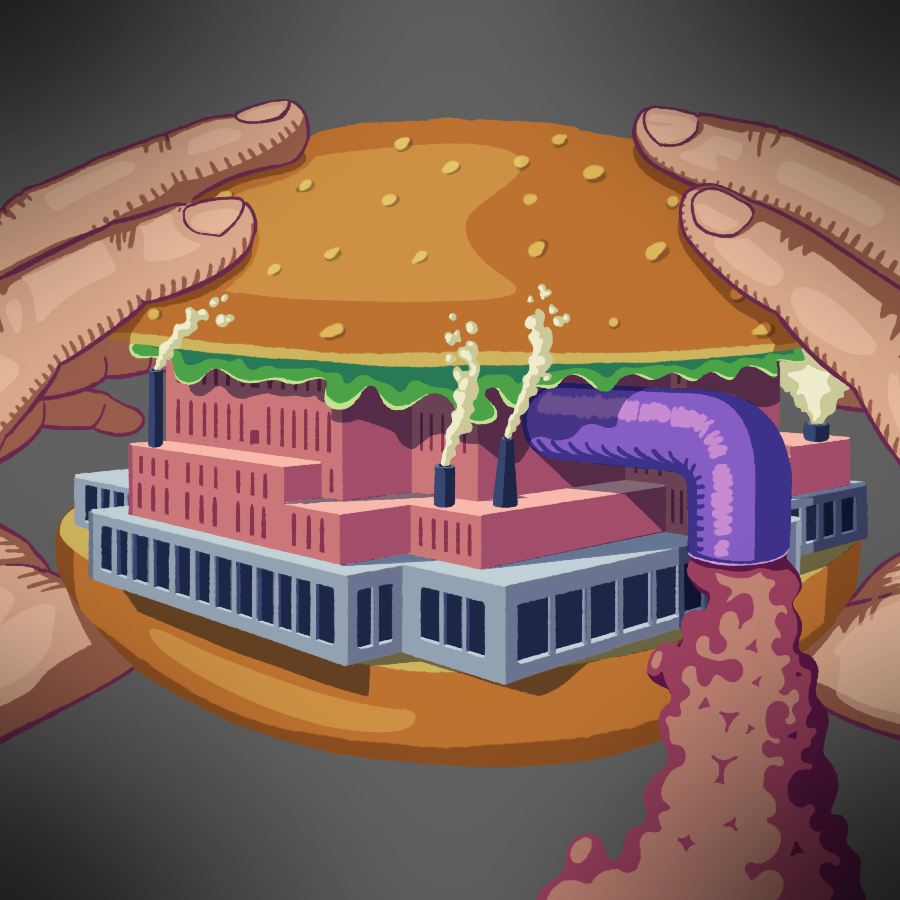

Food and drink are essential ties to our idea of culture. Our memories, experiences and decisions are often shaped by our relationship with what we consume. But the centrality of food to the human experience – including how it is produced and distributed – means it is also inevitably political, and thus can be harnessed to push certain political narratives.

So how can we ensure the politics of food is used to advance social liberation as opposed to pure reaction?

The power of what we eat

To delve into this further, I spoke to Lewis Bassett, a chef and host of The Full English podcast, about why food looms so large in everyone’s mind.

“Food is far more than sustenance,” he tells me. “Psychiatrists think that brains are wired to consider food on three levels: as fuel, as a source of pleasure, and as a social marker. In terms of the latter, that’s why, for example, we might eat cake at a wedding even if we are not hungry or don’t find cake pleasurable. So what we consume is one of the many ways we navigate our culture, and culture is one of the ways we navigate politics.”

This relationship between food and culture gives us an unparalleled reliance on and familiarity with the concept of food. This can assist social movements but can also be taken advantage of. The imagery of food has often been manufactured and manipulated by those with power to convey particular myths.

Food and drink as pushing narratives

Tea is a salient example. Symbolically associated with Britain but being an Asian import, tea was a crucial part of the British Empire.

Its centrality to trade in the imperial core should not be understated. Britain came to rely on slavery and exploitation of local people on the growing number of tea plantations in South Asia and East Africa to continue this profitable trade. The idea of bringing tea to the British masses involved a deliberate strategy to divorce the concept of tea from its actual origins. As the food historian Seren Charrington-Hollins told The New York Times, Britain “used every bit of protocol and propaganda to be sure tea was seen as a British product.”

Obscuring or downplaying the ethnic associations of tea had the effect of reinforcing British nationalist supremacy, and refusing to recognise the struggle and contributions of thousands of Indian, Sri Lankan and Kenyan workers, who toiled to harvest the labour-intensive crop for little return.

This fits into how the symbolic image of certain foodstuffs has been tied to maintaining an entrenched class system throughout the enforcement of empire and capitalism.

A subtle indication of this can be seen with something as innocuous as the British brand Yorkshire Tea, produced by Taylors of Harrogate, established in 1886. If you didn’t know anything about Britain’s climate or history, the name and the box design lends itself to assume the tea is actually grown on fields in Yorkshire, when in reality its tea originates from a range of countries in Asia and Africa. The famous ‘English Breakfast’ tea is actually a blend of over 20 international teas.

Yorkshire Tea do not explicitly hide where their tea is from, and have stated that the name simply relates to where their tea is mixed and made into teabags, etc. However, because the tea comes from countries which were once conquered by the British Empire, just the name creates an aura of unspoken ownership of the tea in its entirety. This is even evidenced by certain social media users getting angry when they realise Yorkshire Tea is not, in fact, from Yorkshire at all.

Despite tea-drinking in the UK being on the decline, the connection between British identity and a cup of tea has been secured for centuries, thanks to a deliberate strategy to move away from Chinese tea and embrace Empire tea.

As ever, we can see the rolling effects of colonialism still resonate today. This is one illuminating example of how food and drink can obfuscate its origin, functioning effectively as soft propaganda for colonialism or national myths.

Freedom Fries

Another, perhaps more egregious, example came out of the US-led 2003 Iraq invasion. After France refused to back President Bush’s illegal military action, a bizarre reactionary trend took place across the US which saw many establishments rename French Fries ‘Freedom Fries’ as a snub to France’s decision.

This attempt at a culture shift was purely hierarchical – it was initiated by two Republican lawmakers who ignited a media circus when they changed the official name for fries on menus in the cafeterias of government buildings. This practice soon spread to private restaurants across the country. Somehow even more absurdly, Air Force One also took to renaming “French toast” as “freedom toast.”

At a base level, this was a naked attempt to subvert an ordinary foodstuff – which has a name most Americans likely don’t think twice about – into a jingoist slogan with shades of xenophobia and nativism. Although the trend did not endure (even the creator came to regret his own creation), the power of this attempt at culture shift should not be taken lightly.

The whole affair reproduced and reinforced anti-French sentiment in the US, to the point where boycotts of French products were called for. American mustard-makers French’s even put out a statement that, “The only thing French about French’s Mustard is the name.”

This shows that even the most mundane food is not spared usage as gaudy political capital.

The presentation and image of food here was used to push a narrative which encouraged cultural divide, and delivered the message that the ruling class wanted – stand with us or be marginalised. This relates to cultural hegemony – the idea that culture is top-down imposed within capitalism and serves to reinforce existing power structures.

We did not see any progressive activist movements oppose the war by trying to give food products more peace-promoting names, as the necessary clout and influence to achieve this simply does not exist as an option for the majority of society.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Flipping the dinner table

The point of these examples is to show how powerful the idea of food can be, and demonstrate how we should strive to use food the way the ruling class do – as a tool of change – but instead for actual progressive purposes.

Using food in this way can come in many forms, including quite literal and physical examples. Egging and throwing vegetables at right-wing politicians has a rich history but in the last few years has manifested in the practice of ‘milkshaking’, with famous targets including divisive figures Tommy Robinson and Nigel Farage.

The point of using milkshakes in particular, with their messy and viscous appearance, is purely to ridicule, reducing the might such characters like to project of themselves. It undercuts their image as the presentable face of xenophobia. As writer G. D. Forrester put it, “these people are salesmen. And no one’s buying from a salesman who has milkshake all down their front.”

Using food in a physical way against hate-mongers is a direct and highly visible retaliation against the kind of toxic rhetoric they spew, and indeed the real violence they inspire.

Although one could argue that the choice of using food to disrupt is secondary to the aim of the tactic, the association of these actions with actual food lends it some originality and notoriety in itself; it helps make a political point with humour and a healthy dose of humiliation. The practice became so prolific that the milkshake found itself something of an anti-fascist symbol. The furore which emanated from this trend showed at least a base level of effectiveness, and a great example of a simple way to utilise food as a protest.

We can see the physical use of food as a protest piece even more in response to the climate crisis. Just Stop Oil protesters infamously took to throwing food at famous paintings as a way of highlighting the urgency of the climate breakdown. Tomato soup and mashed potato being draped over Van Goghs and Monets (although the actual paintings were covered and thus not actually damaged) was a startling image, and inspired a range of hot takes on its effectiveness as a tactic.

Without getting too bogged down into the merits and demerits of the approach, the striking and bizarre look of the food used contrasted to the seriousness of the climate emergency before us.

The ridiculousness of seeing bright orange soup on a Van Gogh painting served as a gateway to starting the real conversation about changing society, one that is sorely needed but not being had. Although paint is often also used as a protest tool in a similar way, the uniquely messy but familiar look of smeared or spilled food has further resonance as an eye-catcher and conversation-starter, at the very least.

Food: the great uniter

The culinary pushback also comes from mobilising the unifying nature of food. As Lewis elaborates on this point, “Food clearly unites people. Think about restaurants which cater to diaspora communities. This is seen even with British communities on the coast of Spain who often love to eat at English cafes, possibly more so than they did when in England.”

Lewis also sees forms of protest in something as simple as the invention of a dish by immigrant communities to “recreate their sense of home in a new setting.” The meal fish finger bhorta is a salient example.

Popularised by Nigella Lawson and journalist Ash Sarkar, the dish is made from mashed fish fingers, fried onions, chilli, garlic and mustard, and has gained attention as a Bangladeshi dish which feels “distinctly English” due to its specific ingredients.

“That dish is really important because unlike the chicken tikka masala, which was created by immigrants for a white British consumer, the fish finger bhorta was created by women of Bangladeshi descent who wanted a familiar taste in an unfamiliar setting. That experience is not only how new, wonderful food is created but also how new national cultures are formed.”

Lewis goes on to argue that the inception of this dish was a form of protest, since “there remain many people in this country who do not want to see immigrants integrated into our national culture, or, more importantly, certainly do not want those people to be agents of their own integration, and in the process shift our understanding of national culture.”

“I think the fish finger bhorta is a deeply radical plate of food in that way since it not only requires the person who made it to adapt to their new setting, but it asks of the white person consuming it to accept something new which was not actually made for them, on their terms.”

In this sense, the power and creativity of making tasty dishes that cross cultural boundaries, often using whichever ingredients are available, functions as a signal that immigrant communities can thrive in often hostile spaces, and expand on the existing culinary traditions in-country to protest any stifling of their identity or presence.

Using food in our communities

When discussing the politics of food, we must address the realities of food insecurity.

According to government statistics, 4.2 million people (6%) in the UK were in food poverty in 2020/21, including a shocking 9% of children. Due to the brutal policies of austerity pursued by the Conservative party, it is often up to us to nourish those in need within our own communities.

At its core, political activism relies on the power of communities, of which food is an inescapable tenet. Harnessing this can have an impact – mutual aid networks, autonomous organisations which organise to care for their own communities, are the most prominent example. This can include check-ins, running errands, food shopping and cooking meals for vulnerable people.

However, when discussing the community relationship to food, it is important to not fall into the trap of taking the corporate line of why food shortages exist at face value.

Large corporations such as supermarkets do discuss community and invest in food projects, but often as a PR exercise, without actually questioning the system which allows food poverty to perpetuate. An example was seen recently when UK supermarket Waitrose used the phrase ‘Perfect for the food bank’ to market stock powder, which seemed to encourage the continued, widespread use of food banks in Britain – something which should not be normalised but scandalised.

Aiming to avoid this is why mutual aid as a practice is more tied to the idea of social cohesion, emphasising solidarity instead of charity.

Charities which redistribute food waste to be used are of course helpful and less wasteful, but hands autonomy to supermarkets to give up their surpluses without asking how the system allows such huge surpluses to exist, and why needy people are reliant on the goodwill of huge corporations which have no accountability. Unfortunately, it ultimately serves to help prop up the proportion of waste that supermarkets produce. Why does 40% of food produced globally go to waste at all?

Understanding this acknowledges that the politics of food, and its use in all kinds of practical or disruptive ways, has to go hand-in-hand with other forms of activism which ultimately aims at complete system change. As writer Elara Shutley put it in her Vittles article, Feeding the Problem: Community, Charity and Corporations:

“If we want the word ‘community’ to mean something more, we need radical approaches to food that can exist without a reliance on those who contribute to the root causes of widespread hunger. We need to resist the constant washing of extractive practices under the guise of community good…Ultimately, a ‘community’ solution to food cannot exist without a rise in the minimum wage, better social housing, and improvements to basic services.”

Make Food Great Again

Using food in creative, disruptive ways can help shift narratives about what food means, which can counter attempts to engineer food as symbols of reactionary politics. But any community initiatives have to realise that community means more than simply tempering capitalism’s worst excesses – we need culture shift to come alongside changing our relationship to food from top-down to bottom-up.

Following the examples of activists who use food in their protests, fish finger bhortas and mutual aid networks, we need a culinary landscape which means cultural absurdities such as Freedom Fries will never rear their ugly head again. This moves forward in tandem with social and cultural liberation. This perhaps brings a new meaning to that timely socialist demand: ‘Bread for all, and roses too’.

What can you do?

- Subscribe to Vittles newsletter

- Listen to Lewis Bassett’s Full English podcast

- Read ‘A Dark History of Tea’ by food historian Seren Charrington-Hollins

- Look into grassroots organisations such as Growing Communities based in Hackney/Haringey, which aims to change the system around how we farm and eat instead of just mitigating its worst excesses

- Help out with your local mutual aid support group

- Read about Why we need creativity and humanity in our prison food