Raï literally means ‘opinion’ in Algerian Arabic, which instantly tells you what this music genre is about – speaking unabashed truths.

An undoubtedly Algerian phenomenon, Raï is a blend of traditional folk over rhythmic drums, often with socially-conscious lyrics, which has become synonymous with the spirit of the nation.

Though its popularity has ebbed and flowed for a century, with its sound and style transforming in the process, its significance as a cultural force has only increased.

This speaks to its legacy not only as a genre of music that pushes boundaries, but as a voice for the underclass and the unheard, with all the struggle and resistance this entails.

Anti-colonial beginnings

Raï originated in the 1920s, in the cabarets and clubs of the vibrant port city of Oran in French-occupied Algeria. Known as the ‘little Paris’ of North Africa, Oran housed a mix of different cultures – traders from France and Spain mingled with the growing urban underclass of local factory and dockworkers. These influences collided to help birth the genre.

Raï started with frank, improvised lyrics about the social justice issues of unemployment and poverty, as well as topics of love and lust. It immediately distinguished itself from traditional poetry through open, sometimes vulgar, critiques, addressing controversial political topics such as the behaviour of colonial police and settlers. Performers often used slang and local, informal Arabic, taking loan words from French and generally spoke from, and to, a working-class perspective, which meant it was looked down on by ‘polite society’ in Algeria.

The music itself used flutes and drums, and had Bedouin tribal influences. The relatability of the lyrics to Oran’s working-class populace, against the hypnotic beat, meant it became an underground sensation in the city. Its words addressed the growing economic woes and disparities present in a society under French imperialist rule, and were also notable for breaking social taboos by speaking openly on romantic and sexual themes.

I spoke to Soumia Lounis, a fan of her national music, who was born in London but spent her formative teenage years with her family in the Saoula area of the capital Algiers. We discussed how her conception of Raï as a genre connects her to the anti-imperialist struggles that came before her time.

“Algerians are very traumatised people. We still have a lot to work through,” she tells me in her South London home over a cup of tea. “Apart from the beat and sounds being amazing, Raï is emotive. It is super emotional to listen to, especially if I pretend to be my mum listening to it as a kid or way back when it was born during the occupation. That’s not something I’ll ever fully understand.”

She adds, “Even though I didn’t experience life during the French occupation, I think it still shapes you generationally. I do my own research on it. Raï music is a nice way to connect to the experiences before me.”

As Raï took on a more cohesive form into the 1940s and became known across Algeria, it also emerged as a rare voice for women – long-marginalised in society – to speak of their ills, often in a bawdy manner not at all common at the time.

The most famous of this era of Raï singers was known as Cheikha Rimitti (‘cheikha’ being an honorific title given to female singers, particularly those who were considered outspoken). She is still considered the ‘Queen Mother of Raï’, as she very publicly and honestly sang about intimacy, femininity, the woes of the poor, and the vices of alcohol and sex.

The way Cheikhas like Rimitti sang frankly about taboo topics shocked many, but enticed others. Raï was giving a voice to a whole segment of Algerian society entirely absent from mainstream discourse and culture, especially one tightly controlled under French colonial administration. Raï was cementing its place as “a musical statement rebelling against political, social, and religious constraints,” as defined by ethnographer Nasser Al-Taee.

As Algeria moved from a French colony to an independent state, with its own ambitions but also internal schisms to deal with, Raï also shapeshifted with the times.

Raï sleeps, but never dies

During the turbulent period of the 1954-1962, where the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) fought ardently for independence from France – eventually succeeding – Raï artists continued to gain momentum, even managing to record many songs for the first time. A newly sovereign Algeria, however, did not encourage the genre to grow.

On the contrary, the independent state actively stifled Raï, preferring to favour more traditional or respectable forms of national music such as Andalusian – which incorporated religious and classical themes over the perceived vulgarities of Raï. The liberation party FLN, though seen as politically progressive for their role in the revolution, remained socially conservative, and catered to the prejudices of the educated middle classes by attempting to ban the import and export of cassette tapes.

However, perhaps fittingly, Raï remained the covert favourite of many Algerians. Bootleg copies of Raï cassettes and records were quietly traded during its crackdown, and the genre flourished underground.

This coincides with Raï’s image as a subverted form of national music – the more it was pushed underground, the more authentically alternative it became. Its endurance to survive and thrive throughout the turbulence of modern Algeria is a testament in itself.

The 1970s and 80s saw an explosion of Raï’s popularity in Algeria, but especially in the North African diaspora in France and other parts of Europe. In this evolution, it took direct influence from other genres such as reggae and rock. Raï was transformed from an underground cult-favourite to a mass-marketed power genre, slickly produced with overlays of electronic synthesisers and drum machines to reach a broader mass of people and situate itself as a modern, popular form of music.

The new ‘pop Raï’ artists, by now mainly male and often speaking to the frustrations and hopes of the urban working-class, named themselves ‘Cheb’ or ‘Cheba’ (meaning ‘young’) to distinguish themselves from, and pay tribute to, the older classical Raï artists who still continued the original Raï traditions (the ‘cheikhs’ and ‘cheikhas’). Superstars like Cheb Khaled propelled Raï to an international stage, playing gigs across Europe.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

It was this iteration of Raï which is most fondly thought of: often a point of pride and celebration by Algerians of all ages.

“Even though Raï has evolved, my generation still listens to ‘old Rai’ such as Cheb Hasni,” Soumia adds. “That’s what we used to listen to at weddings growing up, it’s still such a big part of our culture.”

“I listen to Algerian music in my day-to-day. It brings me back to a safe space, a happy time. It makes me very nostalgic… it brings me home.”

Rising from the Black Decade

The Algerian state’s relationship to Raï was not clear-cut at this time, even with the genre’s potential to be a cultural coup for the young nation. Raï was still controversial due to its hedonistic and transgressive associations. Its poetic lyrics also often referenced lovers who were breaking taboos and freeing themselves from social shackles, which were sometimes perceived as an implied call for political change – a veiled repudiation of the FLN, who had been in power since 1962.

Raï also began attracting a more youthful crowd, a demographic who lacked prospects due to nationwide economic decline and had no personal memory of the 1962 revolution. This meant they were more politically volatile and likely to disrupt the current system under the FLN’s rule.

Due to the popularity of Raï in France mounting pressure on the Algerian authorities, the FLN switched from oppressing the scene to co-opting and adapting it, monitoring lyrics and allowing concerts in-country under state supervision – including festivals in Algiers and Raï’s birthplace of Oran in 1985. This practice could be compared to the US state co-opting jazz music, with the CIA practising ‘jazz diplomacy’ abroad – meaning they sponsored jazz greats like Louis Armstrong to tour parts of the Global South, whilst concealing the motive to use these gigs as a front for gathering intelligence and fighting the Cold War.

This mainstreaming of Raï allowed the state to ride the bandwagon of its popularity in an attempt to quell the growing unrest of the youth due to widespread corruption, unemployment and inflation.

The energy of the unheard was not stifled so swiftly, however. In 1988, discontent reached a boiling point and widespread riots occurred in Algiers and elsewhere, which were bloodily suppressed by the state, leading to over 500 dead. The protest lyrics of Raï were blamed and scapegoated by President Chadli Bendjedid as responsible for the attempted uprising, rather than the material conditions of the population.

Though the president blaming the musical style was clearly a political statement – akin to politicians blaming violent acts of young people on hip-hop, grime or drill lyrics – the fact that he used it as a scaremongering tactic speaks to its presence in the popular imagination. It had a reputation of being disruptive enough that it could allegedly influence people to revolt, or at the very least voice their concerns.

And indeed, Raï did have a presence in the upheaval of the 80s. Crowds of demonstrators chanted the words from Cheb Khaled’s El Harba Wayn (To Flee, But Where?), with the radical lyrics making it a powerful protest anthem:

“The rich gorge themselves, the poor work themselves to death … you can always cry or complain. Or escape … but where?”

Young people were expressing their distrust and disappointment in the only system they had known, using Raï lyrics as a beacon of rebellion.

The tensions in Algeria did not dissipate, and in the early 90s, an armed struggle between the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) and the ruling FLN soon culminated in a civil war, in what is known as the ‘black decade,’ a painful memory which still resonates today.

Frequent bouts of violence and suppression meant culture was an incidental casualty. Musicians, artists, filmmakers and academics were caught in the crossfire and Raï was no exception. Indeed, singers such as Cheb Hasni, and producer Rachid Baba-Ahmed were even killed, the former allegedly for kissing a girl during a recorded live concert.

Due to this friction, the sad reality is that a lot of Raï artists and producers simply relocated or self-exiled, mainly to French-speaking parts of Europe. This situation produced the irony that Algerian artists became extremely popular in the country of their former coloniser – not just to the North African diaspora but to a new, white audience who were sympathetic to the anti-racist struggle.

Evolve and adapt

As France became more of a hub for Raï production and promotion, the genre regained some of its political roots – standing as a symbol of Algerian pride outside the repression of its own state. This was especially significant against the backdrop of the rise of the Front National in France but also notably the 1998 Paris World Cup, which propelled star French player Zinedine Zidane, of Algerian origin, to prominence. Ideas of North African unity gained traction, as did celebrations of multiculturalism and anti-racism, as seen with the SOS Racisme movement, in the face of the rise of Islamophobia and the far-right.

Algeria had hit the main stage in the European imagination – it was cool. The style of modern Raï helped to promote Arab representation in the mainstream and tackle racist sentiments, in France especially.

Raï also morphed into offshoots, evolving in ways to keep appealing to the young. It blended with new genres to become Raï’n’B and other fusions like rap Raï, cementing its cultural resilience. It is also significant that in 2022, Raï was officially recognised by UNESCO as an “intangible cultural heritage” of Algeria.

While it has undoubtedly become more commercialised since its inception and its 1980s form, modern Raï still has a twang of social commentary, often touching on issues that affect the Algerian diaspora such as policing, racism and unemployment. In a sense, many of these issues are the same ones Raï singers first opined on a century ago. The circumstances have shifted but that core yearning for freedom and justice remains.

Raï to the future

As a result of Raï’s staying power and rebellious spirit, its legacy can be felt wherever there are Algerian communities.

I was lucky enough to recently attend London’s DzFest – a celebration of Algerian music and culture. There I watched the fascinating documentary A little for my heart, a little for my God, which explores the power of rhythm and Raï in the form of meddahates, female singers and musicians who perform exclusively for other women at weddings and celebrations, in Oran in 1991.

What stuck out to me from this intimate glimpse into Raï being performed live in Algeria during this period was the surreal, dreamlike atmosphere that it emanated. Eclectic crowds of women in elaborate dresses cramped into hot, sweaty rooftops, (almost) all-female troupes playing relentless beats on the bendir (hand drums), singing and performing with such passion. The dancing from guests and performers alike was hypnotic andtrance-like, a true surrender to the Raï rhythm.

It was the best illustration of the power of Raï. As one of the older cheikhas interviewed in the film comments, “Raï music makes you lose your head.” I really felt that!

The audience for this DzFest event was a mix of Algerian nationals, second generation members of the diaspora and culture vultures. I had some interesting interactions with attendees, which began after someone noticed we were wearing the same Palestine t-shirt, but soon moved to the topic of Raï.

“Have you noticed that modern Raï music is so vulgar?” asks a young fan, who is Algerian but born in the UK. “It surprised me since we are always told Algeria is a conservative society.”

“But Raï has always been like that,” replies an older Algerian woman, who speaks warmly of seeing Raï artists like Cheb Mami and electric rockers Raïna Raï in a concert in Algiers in the early 1990s. “They have always been about breaking taboos.”

Soumia agrees with their assessment too, “Rai is a massive defiance. It’s such a testament to what musicians can use as an outlet. It’s a way for people to speak on things that are taboo, that they can’t actually say out loud.”

The genre lives on. A “Raï-naissance” of sorts has meant that Raï classics have enjoyed a comeback, alongside the modern Raï/hip-hop fusions still capturing the youth.

Raï went through the struggles that Algerian people faced along with them – being pushed and pulled by different forces, claimed by some, shunned by many. Though its censorship and restriction (at various stages in modern Algerian history) undoubtedly affected its prominence, the strength of the genre came from withstanding the many threats to its existence, always managing to operate outside the mainstream and have a long-lasting reputation in spite of these challenges.

Raï can’t be pinned down. It is opinionated, sometimes alienating in its lyrics and language, but always has that spark of the underclass, that edge consistent with its unique history and evolution.

“It’s a nice way for Algerians who are born away from Algeria to connect,” Soumia tells me. “When you start reading about Algeria’s history and understand that Raï is a reflection of that, it’s a way for me to understand what people went through. Because it’s so raw and real, there’s no pretence. It just happens to sound nice coming out of their mouth. They’re spitting bars, it’s impressive!”

As the great Cheikha Rimitti herself said: “Raï music has always been a music of rebellion, a music that looks ahead.”

Special thanks to Stephen Wilford for helping shape this article.

What can you do?

- Check out the Arte documentaryRaï is not dead

- See Acid Arab’sbrief history of Raï in 5 tracks at Stamp the Wax

- Listen to the Shakshouka w/ Cheb Mimo NTS radio show to hear a spectrum of Raï-blended tunes

- Check out DzFest, the Algerian arts and culture festival in the UK

- Get involved with Culturama, which promotes Algerian traditions in the arts

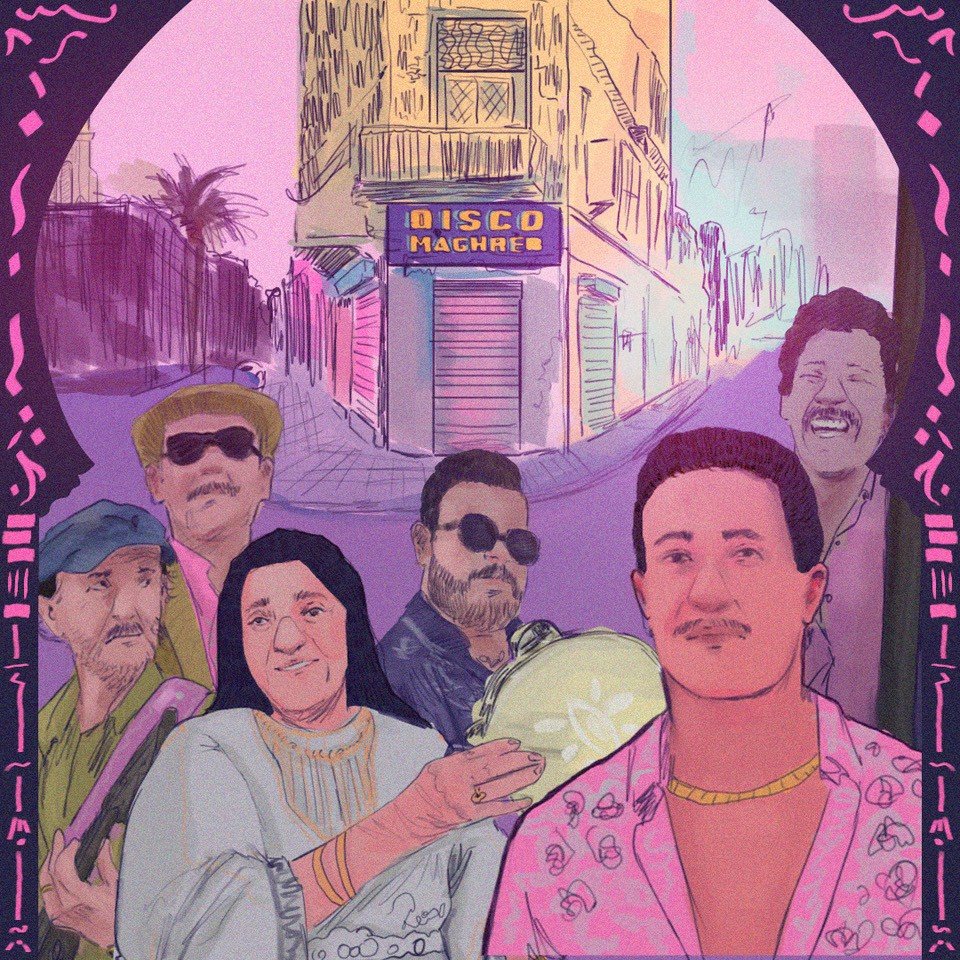

- Read about Disco Maghreb, the iconic record store and music label in Oran, which had a revival due to French-Algerian producer DJ Snake’s 2022 song of the same name

- Read ‘60 years on from the French occupation of Algeria, and my heritage is still lost’ by Leila Gamaz for shado

- Watch the 1966 film ‘The Battle of Algiers’ about the Algerian War of Independence

- Read: The New Song Movement: Latin America’s soundtrack to the revolution

- Read more pieces by Tommy HERE

- Subscribe to the shuffle, a substack by Tommy HERE