Before she could even walk, Maïa Barouh found herself in the groove. Going along to shows with her parents as a one year old trying to stand up and dance to music was just the beginning of what would become her life-long experimentation with rhythms, melodies and harmonies from around the world.

Now, the immensely talented Franco-Japanese singer, flautist, songwriter and producer shares the inspiration behind her latest album AIDA, her personal mission of building bridges between cultural tradition and reinvention, and her thoughts on the place of satire and joy in art which calls for change.

AÏDA: “What it means to be in between”

“I feel this mission of being in between as a Hafu, of making this bridge between things and finding this place that connects them,” Maïa begins. Hāfu – the common Japanese term which translates to ‘half’ in English – is a nickname both Maïa and I share. Although it generally refers to people who are ethnically half-Japanese, it’s increasingly become a catch-all term for all multiethnic people in Japan and the diaspora.

Attitudes towards the word differ, but some people take offence to the term because it implies lack or ‘impurity’ and prefer to opt for alternatives like ‘Daburu’ (double), Mikusu (mixed), or ‘Hapa’ (originally a Hawai’ian word used to describe mixed-race people) – which champion the fullness and beauty of multi-ethnic heritage.

Growing up between her parents’ home countries of France and Japan and coming to terms with her own mixed roots was part of the inspiration behind ‘AIDA’ – Maïa’s latest album, which translates to “between” in Japanese.

“Even after all this time,” Maïa admits, “there’s this strange feeling of being so strong but also so fragile, feeling free but unstable by not belonging to somewhere.”

Hoping to resonate with an audience grappling with their own struggles of belonging and self-understanding, she sonically dives into these conflicting notions by fearlessly refashioning and cross-pollinating genres and musical techniques to create her own world of sound.

Instead of imagining occupying the space ‘between’ social categories as one of constriction or rejection, AIDA aims to create and explore the vast potential of this unique place from which new ideas can emerge. Whether it’s the space between what it means to be ‘just’ French or ‘just’ Japanese, the space between musical genre borders, or the space between traditional times and now – you can see how this album is, in many ways, the story of Maïa’s life.

Tradition and reinvention

Unafraid of inhabiting the liminal space between what’s been known and what is to be born, she makes a point of paying respects to tradition in her own way – through experimentation.

Think Tokyo underground meets Japanese Blues and Folk music meets French electronic and Rap scene meets Tribal Groove moments. But defining her music into a multi-hyphenate genre is almost a pointless undertaking because it is far more than the sum of its parts.

For Maïa, blending these cultures together isn’t for novelty’s sake. In fact, it’s a path to cultural preservation through reinvention and transplantation.

She takes this approach with Japanese traditional music and blues for example, which originate from workers in the rice fields and fishermen.

“These songs are not really like classical music with partitions that you have to sing or play a certain way,” she explains, “they’re really free and transmitted orally through generations.” There’s even great variety within these genres themselves, with different styles from village to village, from city to city, from north to south to east and to west. Sometimes mixing these styles together and with other non-Japanese genres in her music, she creates a bridge between these worlds.

This is radical from many standpoints, especially given Japan’s attempts to present itself as a ‘pure’, ethnically homogenised country.

One doesn’t have to look far for examples of its historical attempts to suppress Indigenous peoples such as the Ainu, the Ryukyuan, and the Burakumin – not to mention the ongoing discrimination towards ‘Zainichi’ Koreans. By acknowledging the diversity within Japan through her music and bringing it to the world’s attention through integration with other genres, Maïa’s experimentations play a pivotal role in championing these cultures.

Recently, she has also taken inspiration from a technique used by the people of Amami Oshima – one of the Satsunan Islands in the Japanese archipelago.

These folk song masters, known as utasha, employ this emotive method to emphasise smooth transitions between a high falsetto register and lower pitches. Recounting her experiences of visiting Amami and seeing younger and older generations singing these songs together, Maïa commented “their way of singing is really special – it blew my mind – technically it’s more similar to Iranian songs or Yodelling or Mongolian singing than Japanese music I’ve heard.”

I was lucky enough to have a demonstration from her mid-interview – she challenged me to find a way to type it out phonetically but I don’t think it will do it justice. Instead, you can hear it for yourself on her song chinXoise.

Maïa’s confidence and willingness to slip in and out of new genres and constantly improvise is attributed to her solid musical foundations playing classical piano from the age of 6, and guitar from 15. Quickly picking up the flute, she switched to more jazz and improvisation, performing professionally as a musician by age 17.

Likening the flute to a snake that slides through all kinds of music, choosing this as her main instrument allowed her to commune with world music even if she didn’t know the spoken language. “All the things I learned at the beginning really enriched me and so when I started the flute I was already rooted,” she explains.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

What do we take from all this? As nice as it would be, sometimes we can’t protect the heritage of techniques or genres through generations by continuing to replicate them bar for bar, especially if they come from cultures which have been marginalised or bypassed.

Instead, these cultures find their eternity through revolution and expansion, interacting with and spilling over into other cultures over time. As Maïa puts it, “sometimes the best way to transmit tradition is to sing it your own way.”

Instantly, this transported me back to a talk at Japan House by Buddhist Bell Artisan Shimatani Yoshinori, where he explained the concept of Shuhari – the three stages of learning for a student. At first there is Shu, where a student closely obeys and repeats the teachings of the master to build the foundations of their wisdom. Then comes Ha, the point at which a student begins to break from tradition and integrates other approaches. The path that Maïa describes resonates more with the final stage of Ri, where a student no longer requires a direct mentor and becomes more of a pioneer, learning from exploration of their own practice and experience.

Integrating this learning approach to my own work as an organiser and activist, I can also appreciate how this helps us build in greater creativity and scale to our movements. We must remind ourselves and each other that we can pay respect to the radical traditions and the knowledge that came before us by further developing them to our personal strengths and contexts – which in turn makes them more sustainable and effective.

Satire in the face of Orientalism and anti-Asian racism

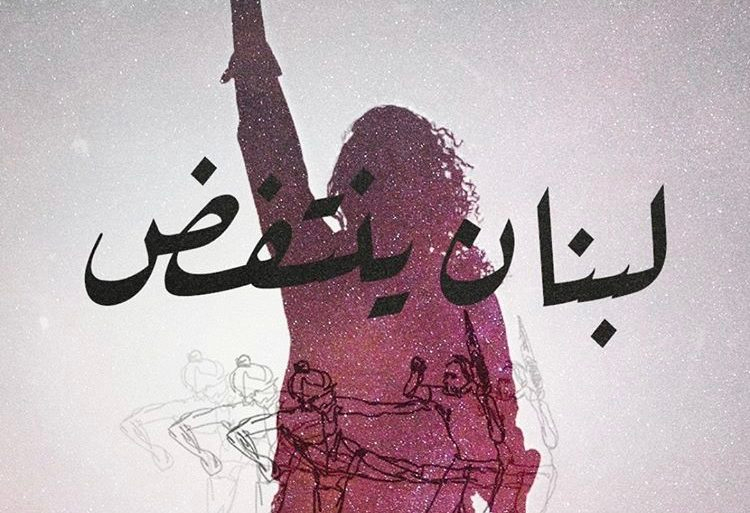

Aside from the distinctiveness of her sound, Maïa’s visuals in her music videos are also striking. With chinXoise, she originally envisioned the video being a full blown manifestation of people marching through the streets and protesting against racism.

The main hook of the song – ‘Non, Je ne sais pas Chinoise’ – emerged from a conversation she had with a French-Vietnamese friend before jamming. It comes from their own shared experiences of getting incorrectly labelled as Chinese by white people, just because they look Asian.

Characterising us as all looking the same as each other, is not just carelessness – it’s actively harmful. Painting Asians as a monolith or just ‘another brand of Other’ ignores the rich diversity and heritage of our respective cultures, as well as our personhood. This dehumanisation in turn fuels the misogyny, fetishisation, and violence we face.

For instance, In the UK, we saw an estimated 300% increase in reported hate crimes against British East and South East Asian communities in the first quarter of 2020 – shortly after the outbreak of COVID-19. Sinophobic rhetoric was rampant and being used to legitimise this violence against our Chinese brothers and sisters – but also the ESEA community as a whole. At the end of the day it didn’t really matter to these racists whether or not we were actually Chinese because to them we all look the same, different from them – and were therefore inferior in their eyes.

In chinXoise, East and Southeast Asian stereotypes are satirically put on notice. Maïa plays an actress on a film set drowning in Japanese cliches being imposed on her by the mini living society of the studio. Technical team, directors, makeup artists, costume designers, and so on are all involved in the process of her fetishisation. Appearing first as a samurai, then posed on top of a Japanese fishmongers table, and later dressed as a geisha, Maïa’s anger at being confined into these stereotypes by others is almost palpable even through a screen. Gradually her frustration builds throughout the song, eventually erupting into a dance of revolt.

By drowning the video with stereotype upon stereotype, she exposes the ridiculousness and absurdity of Orientalism through satire and parody. “It was important for me to keep this kind of humorous and satirical angle,” Maïa explains. “I don’t feel like I’m imposing anything but instead proposing some feelings – and then if people are curious and want to find out more they can dip into the lyrics.”

Embedding this lighter tone into our advocacy can sometimes feel like a risk we can’t afford because everything is so urgent, but the reality is that because we need everyone to make change happen – we’re going to have to accept that we need to meet people at the varying levels they’re at.

Finding roots within one’s self

When I asked Maïa what is the one thing she hopes people take away from her music, her answer was simple: “I want them to think: if I can find my own roots within myself, then I can go anywhere and be fine – I don’t need to fit into anyone else’s boxes.”

This is exactly what she’s expressing with her sound – the radical possibility of occupying a space of the unknown, which doesn’t exactly fit within the confines of this existing world but leaves a trail of notes showing others the way towards a new one.

What we can also learn from listening to and observing her work is that reconnection to our heritage does not always have to mean replicating things as they have always been done. Instead, this can look like rearranging and renewing these practices, imbuing them with our own personal imprint too to help carry them through the years ahead.

As a person of multiethnic Japanese heritage myself, Maïa’s unapologetic presence ‘in between’ the binaries is deeply reassuring to see. My hope is that more Japanese artists of all ages are equally encouraged to take on this approach to their work, so that the true varied picture of ‘what it means to be Japanese’ is there for the world to see and appreciate.

What can you do?

- Keep up to date with Maïa’s upcoming concerts and performances here

- Watch the music video for chinXoise, which appeared on Maïa’s latest album ‘AIDA’ released at the end of 2022.

- Read: Who Gets To Be ‘Hapa’?

- Learn more about the folk music and vocal techniques of the people in Amami Ōshima

- Listen – expand your sonic horizons with Maïa’s recommendations of ones to listen out for:

- Iara Renno – a Grammy-nominated Sao Paulo singer, songwriter, music producer, director, poet & artist in expansion.

- La Chica Belleville – French-Venezuelan musician whose work has been described as a “fusion of pop influence, hip-hop, Latin music and Spanish canton.”

- Témé Tan – Kinshasa born, Brussels raised globetrotter under the influences of Congolese rumba, Malian blues, Afro-pop, zouk, hip-hop, and more.

- Oriane Lacaille – singer, percussionist, ukelelist, author, composer and performer poetically mixing Creole and French languages with her music.

- Elis Regina – Another Brazilian favourite, a singer who was not shy about criticising Brazil’s military rule during the 1960s, and a defender of the rights of musicians and workers in general – creating an association for interpreters and musicians (ASSIM) to preserve copyrights.

- With powerful visual references and cinematography at play throughout chinXoise, here are some of Maïa’s own suggested filmmakers to watch:

- Alejandro Jodorowsky – Chilean-French avant-garde filmmaker, best known for The Holy Mountain (1973), El Topo (1970), and many other works.

- Akira Kurosawa – Considered to be one of the most influential Japanese filmmakers in the history of cinema – lauded as one of the greatest inspirations for George Lucas’ Star Wars.

- Nagisa Oshima – Originally a leftwing student of political history at Kyoto University who went on to become a key player in the Japanese New Wave film movement, many of his films being known for their taboo subject matter including Korean discrimination, xenophobia, queerness, sexual politics and World War Two.

- Read more articles by Isabella HERE