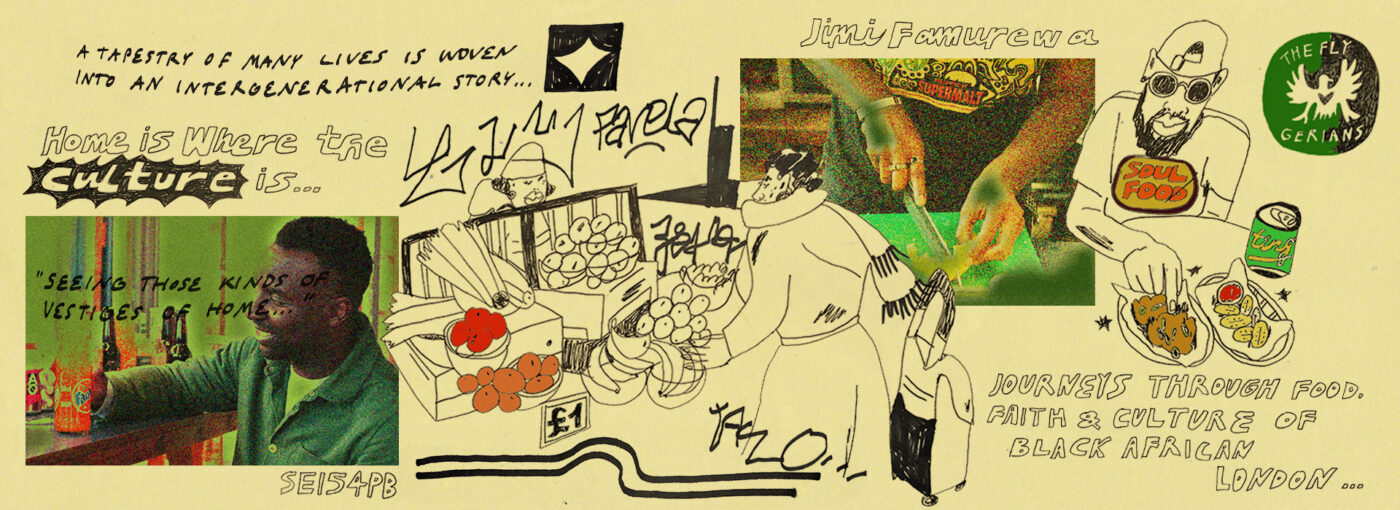

An abundance of scotch bonnet, palm oil and plantain waiting eagerly to be bartered for. Palms caressing the sky in jubilation in the house of worship. The familiar rumble of a never-too-far-away soundsystem. Settlers, a new book by Jimi Famurewa, brings these images to life. He interrogates what it means to be Black, African and British by delving into the everyday, journeying through core cultural institutions from the marketplace and community hall. And in doing so, he creates an intergenerational exploration of our constantly evolving idea of ‘home’ – something we can hold, that holds us in return.

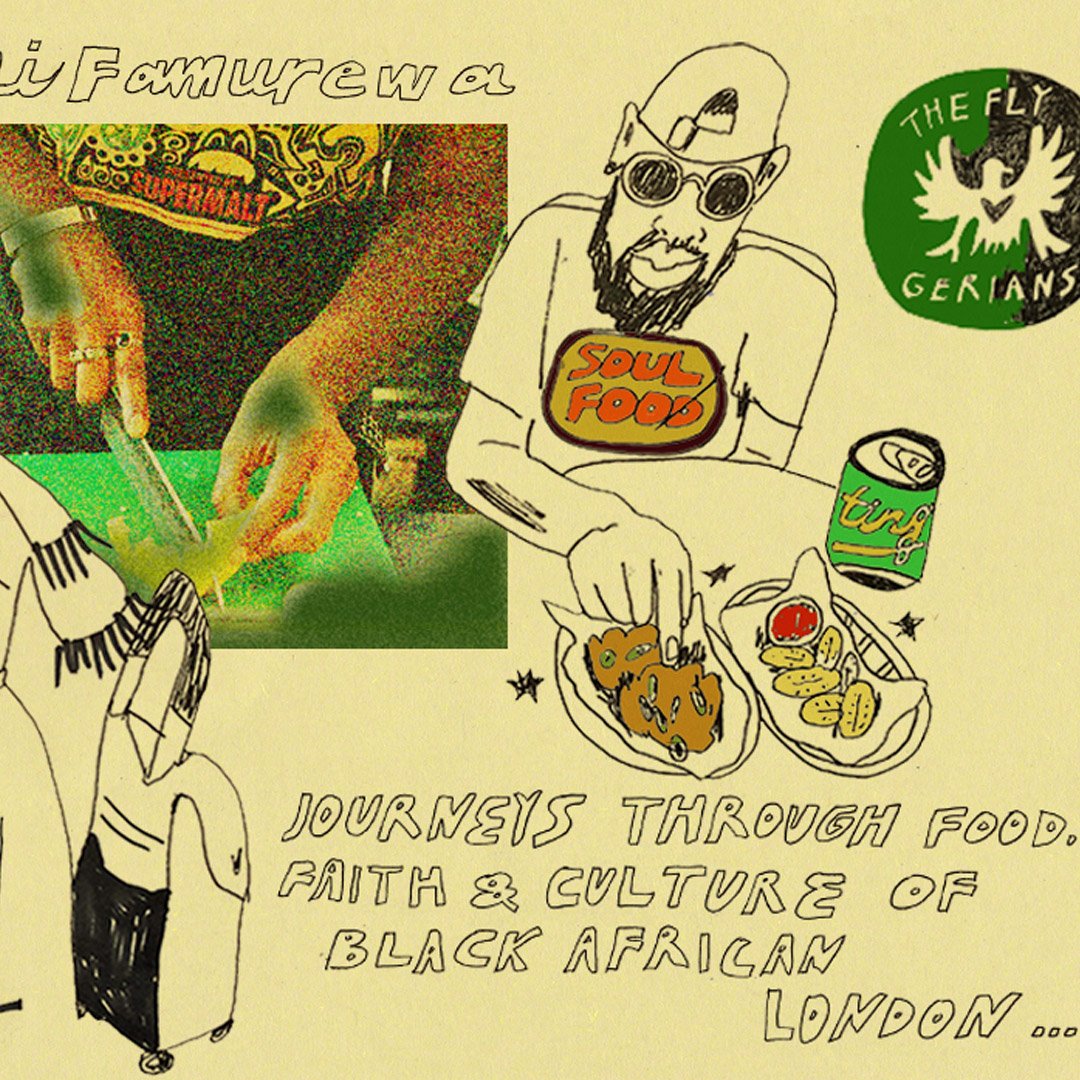

Food and its role in everyday life is a core part of culture – and it goes far beyond sustenance. It is where we celebrate, where we are comforted and how many express their love. Food can provide us with a physiological connection to home, so in meeting Jimi – a talented food critic, regular guest judge on BBC’s MasterChef, and, of course, an author – it made perfect sense to chop it up in Nigerian restaurant The Flygerians, run by chefs and sisters Jess and Jo Edun.

We sat down to talk about the responsibility of telling history, the power of finding home in physical and intangible spaces and speaking to our parents about their migration stories.

Throughout our lives we reinvent ourselves in many ways, from the music we listen to, to the causes that we care about, finding new communities along the way. Within each of these poignant periods of growth, we often discover ways to keep ourselves planted – even if we must uproot on occasion. Jimi beautifully weaves together a tapestry of stories of those who know this change intimately, namely those who left shores known to arrive in a new unfamiliar terrain.

Throughout the course of writing Settlers, Jimi spoke with his mother, who moved from Nigeria to the UK. “That was another really nice thing about the book; that we were able to have those chats. I asked her things that I would never have probably asked her. It was here that we unpacked what it means to see our parents as individuals with their own life story, one that started many years before we came to be.

“Through writing Settlers, I got a renewed appreciation for the sacrifices our parents made,” he says. “I got a greater sense of how chaotic it was for them. You’re protected from a lot of it as a kid. My mum, my uncles and my relatives, all in one flat. I didn’t really think about what they were going through.”

Oral histories are one of the many ways that cultures across the world collect and pass on ancestral knowledge. For Jimi, Settlers created an opportunity to meld the oral with the written through translating spoken testimonials into written prose. “So many immigrant histories, not just Black African, are oral and therefore can be hidden from us. In Settlers, I wanted to, as best I could, excavate a little bit of that.” A well-known proverb from the continent warns that when an elder dies, a library is burning: without passing on these stories and knowledge, we can lose centuries of heritage. “I’m literally setting stuff down that probably wouldn’t exist in any other form,” he says.

For many of our parents, elders and even those who arrived before them, Britain was and remains a hostile terrain to navigate. Those who leave behind a whole land that raised them to begin a new journey in hopes of a better life are among the bravest of humans in this world. A tremendous amount of sacrifice is required. “The immigrant story is so hard,” Jimi muses, “You’re forced to go through your working and day-to-day life being told that you’re mispronouncing things, that you’re too loud, that you act in a certain way that’s not palatable.” Therefore, as Settlers highlights, having a haven where one can drop their shoulders and exhale the struggles of the day has, and continues to be, so important to many of those in our communities.

Jimi reminds us that it can be something as simple as how you talk – “you know, how you relate to people. If you can go somewhere that reminds you that you have a bigger story, you can be filled up by a certain type of joke or a certain type of interaction.” As humans, we habitually seek connection, which can come from within or through physical spaces around us. “They represent that side of yourself, seeing those kinds of vestiges of home,” says Jimi.

Jimi ruminates on how the multiplicities of our identities as second and third generation Black Africans shapes our interactions with – and our claim to – the spaces that our elders may have found home in. “There are times where you crave the barbershop, the hair salon, the rudeness of the shopkeeper you buy your suya or patty from,” he smiles. “I was able to really appreciate these spaces a lot more by getting into the historical context and witnessing people interacting in these spaces. It was a real joy.”

However, he also reminds us that our identities are constantly in dialogue with one another too. “We can sometimes have a conflicted relationship with these places, too,” he says. “There are also times you feel like you want the other side of yourself to be represented,” referring to the new cultures created by Black British diaspora communities. Just as those who came before us, we are actively seeking better for ourselves and this means demanding more from the country whose history of colonial violence cannot be divorced from the history of African migration.

Settlers is exciting for many reasons, but perhaps one of the most objectively wonderful things about this book is in its contribution to a dearth of literature chronicling the lives of African migrants through core activities that punctuate daily life. Whilst the canon is growing, slowly but surely, much of the texts that are available to us on Black African lives look to the past.

What Jimi has captured however, is the now. To do that justice, he considered how his own cultural sphere might influence the lens through which the book would be written. “I wanted to make sure that I’m not in my kind of Nigerian silo and bubble. Nigerian and African obviously overlap, but they’re not interchangeable,” Jimi continues. He says it was important to actively resist the homogenisation of the continent, but also to acknowledge where and why cultures may share in tradition or practice. “There’s so much crossover and so much shared history and specificity within that.” Jollof rice is a perfect microcosm of this: a staple dish made across some West African countries, each with their own unique spin.

Beyond the immediate lessons that the pages of Settlers offer, lay the subtle yet equally poignant lessons that dance between the words – in places and spaces that we may find home, connection awaits your arrival. We each have a story worth telling if not for the present, then certainly for the future. Either way, let’s begin with home.

What can you do?

Buy the book! Read Jimi’s words for yourself here.

Check out Black British Studies: In 2022 I created and taught a university module on Black British Studies, here are some resources from the module that you can use to delve into the beautifully creative, joyful and powerful history of Black British communities in the UK.

Black Studies Reading List: This includes books that weave the oral with the written, documenting Black British lives throughout the decades, as well as those outside of the UK. These titles feel like living archives, the words of those who lived decades ago, still live in the pages of these books. BMODULE20 for 20% of the reading list

Listen: Resistance, Creativity and Joy: Black Studies Playlist. Over 100 songs that capture the evolution of Black British music across the decades, from jungle to grime, R&B to pop.

Support local business:

If you are able to, shop locally at your independent grocery shops and market places. It’s hard to be a conscious consumer in a cost of living crisis and the insurmountable pressure of capitalism, but you can make your coins go further. Shopping locally, can often mean more value for you money whilst supporting the livelihoods of those who make the communities that we live in great – especially if you live in a gentrified area, shopping locally and ethically, can help save shops from closure or being priced out of the areas that many owners and workers may have lived their whole lives.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

A Selection of London’s Black-Owned Restaurants

Nigerian:

- Flygerians in Peckham, South London

- Chuku’s in Tottenham, North London

Caribbean:

- Jam Delish in Highbury, North London (Vegan)

- True Flavours in Brixton, South London

- The Dutchie in Croydon

- Eat of Eden in various locations, London (Vegan)

- Jumbo in Peckham, South London

- Wood + Water in Brixton, South London

West African:

- The Calabash in Greenwich, South London

Gambian:

- Papa L’s Kitchen in South West London

Senegalese:

- Little Baobab (monthly pop-up restaurant in London)

Pan-African:

- Tatale In Southwark, South London

- Stork in West London

Ethiopian:

- Adam’s Ethiopian Restaurant in Brixton, South West London

Ghanaian:

- The Gold Coast Bar and Restaurant in Croydon

Haitian:

- Grill Shack and Tiki Bar in West London

Illustration by Luci Pina @luc.ipina who says: “For this piece I tried to capture the sentiment expressed in the article of connections between food and place. I illustrated a market scene which in my eyes is a simple visual for that merging of cultures, and a place many of us who may feel displaced often find a home in.”

Illustration by Luci Pina @luc.ipina who says: “For this piece I tried to capture the sentiment expressed in the article of connections between food and place. I illustrated a market scene which in my eyes is a simple visual for that merging of cultures, and a place many of us who may feel displaced often find a home in.”