Mohammed Z Rahman is a British-Bengali visual artist and writer based in London whose work explores food, migration and gender.

How has your lived experience shaped your practice?

My background makes me question things wider society takes for granted. [Deep breath before multi-hyphenate identity description] I’m a working-class, class-mobile, queer, second-gen British-Bangladeshi raised in a conservative Muslim community in London. TLDR: it comes with its share of unpacking, conflict and possibility.

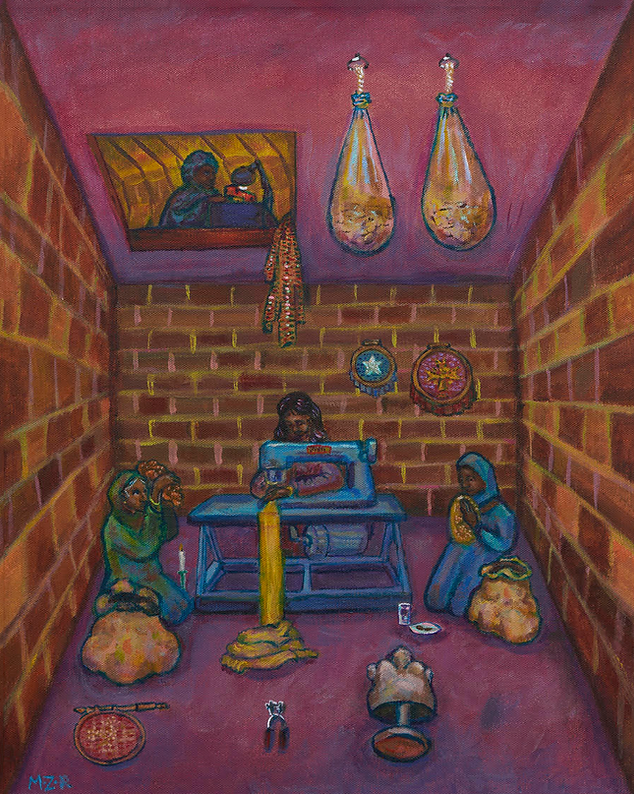

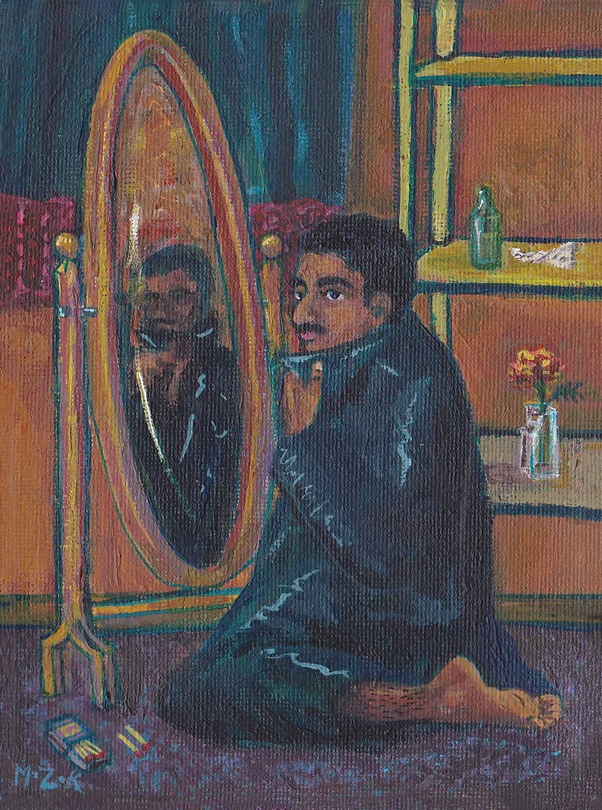

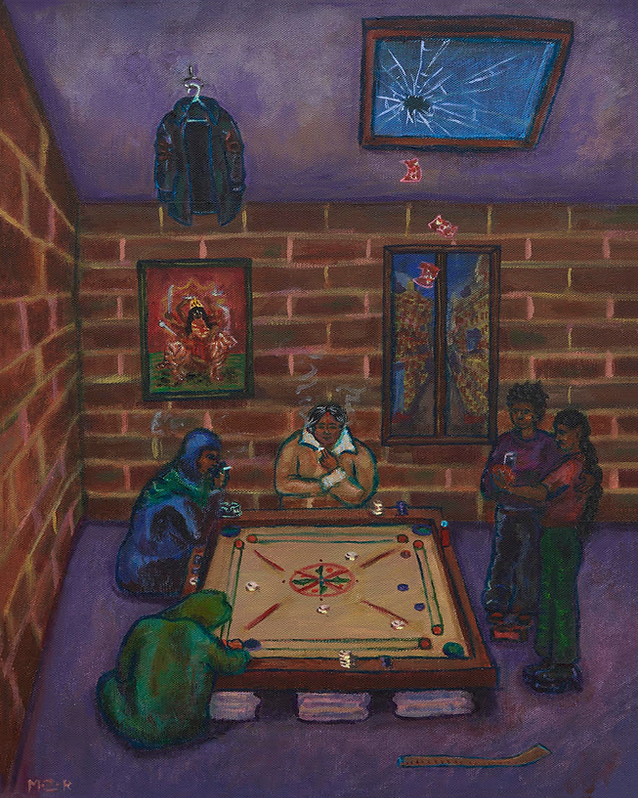

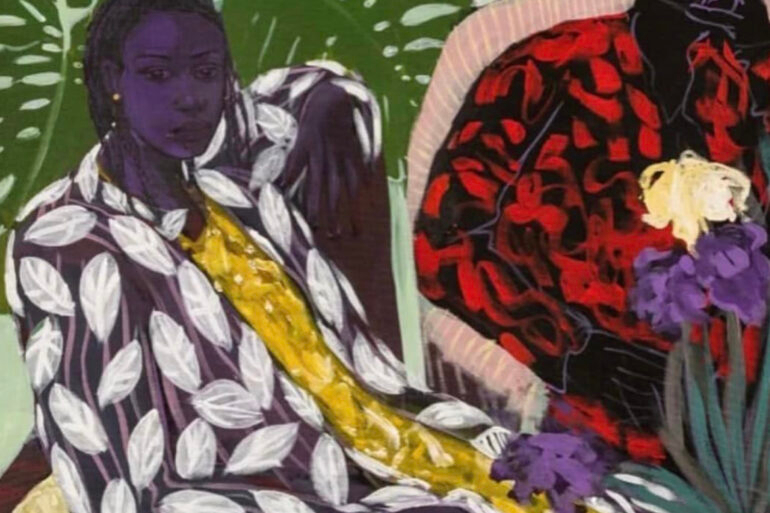

When researching, I’m too-often amazed at how hard you have to dig to access the histories of my people, friends and neighbours. This has shaped my practice in how communicative I try to be to counter various strands of erasure at play; for instance how my paintings are packed with allegory and references across history and geography. I’m no stoic. When I read about the wider socio-politics of migration and gender discourse, I take on the historical detail and also feel the emotionality behind themes of displacement, empowerment, erasure and resistance. I weave wider social phenomena with my own personal narratives to convey a sense of where I and my audiences sit in relation to the wider world and history. I think making pictures carries this kind of socio-political emotionality in ways words alone would falter.

What are some of your biggest influences and motivations in your work? What issues are you passionate about working on?

I’m influenced by artists who have a punchy graphic style and political slant, I particularly love Emory Douglas, SM Sultan and Marjane Satrapi and artists who play with narrative and subvert realism like Salman Toor and Paula Rego. I love writers like Mikhail Bulgakov and Jeanette Winterson for similar reasons.

I take an intersectional approach as it doesn’t make sense to me to silo issues like migrant rights from trans liberation, anti-islamophobia and climate justice- they all inform one another. Nor does it help to constrain history to national borders. While there is definitely a place for separatisms, I understand them as a limited solution in a hostile environment as it quickly becomes a game of defining yourself based on what you’re up against. To me, it’s more fruitful to put these topics in relation to one another to build solidarity and understanding; solidarity is a much realer threat to systems like patriarchy and White supremacy that rely on division to uphold inequality.

Can you tell us more about your focus on objects?

My obsession with material culture as a mode of storytelling comes from my working-class migrant background and anthropological training. Workers’ tools and sentimental objects from childhood have a life of their own; they can cross borders, play roles in nurturing or terrifying us. I construct my images with a writerly logic of plot devices to evoke a sense of drama, namely an interplay between figures and objects. Objects are also the anchor point for where my surrealist style can sink its feet into social realism, they keep the audience understanding that the scenes I depict have, in some way, happened in our world.

On your website you say you aim to create work “that celebrates his communities’ internationalist dreams, disrupts violent power structures and makes peace with unspeakable chaos.” How important is re-imagination in our movement building and what role do you see art as having in this?

Art can help us see beyond our present conditions through fantasy and through it we can imagine new worlds. Art can also depict the everyday which allows us to question our current material reality. I try to have these two functions side-by-side as they work best together and are part of the same process of world-building.

Where are you based and what excites you about the creative community around you?

I’m based in northeast London and grew up in east London which is a great place for someone like me to live because of its diversity. Its migrant communities give me constant inspiration, through the sheer possibility they present on how one can lead a life. I think living in a place like this makes me curious and emotionally invested in my neighbours which has definitely fed into my internationalist politics.

See more of Mohammed’s work HERE