The Abayuuti Community Group was founded by seven friends who grew up in the Kakajjo Zone of the Bukesa Parish in Kampala, Uganda. Rooted in community values, the group leads climate education programmes, supports those impacted by climate change and provides a platform to amplify their experiences. I’m a neuroscientist and environmental justice activist based in the UK. I spoke to Crispus Mwemaho, a Ugandan climate activist and leader of this community group, whose work I was introduced to through Instagram, about how creating a local network of support and resilience is essential for climate adaptation.

For those of us who live or grew up in the Global North, the climate crisis might feel like a recent event which has only just started to penetrate our social consciousness. There are even those, tucked away in right wing pockets of colonial nations, who refuse to believe in its very existence, and many more who don’t consider it something worth their immediate attention, despite the global scientific consensus and the already overwhelming body of evidence to the contrary.

The fact is that many are choosing to look the other way, and it’s often these same people who are celebrating the milder winters and warmer summers, not connecting these temperature changes to the increasingly extreme storms, flooding and heatwaves which are happening all over the world.

However, those who live or grew up in the Global South and previously colonised countries know otherwise. For them, the climate crisis has been devastating their homes and livelihoods for decades.

The impact is also often more extreme due to geographical location, conflict and colonially exploited economies, which in turn has driven further climate destruction, land degradation and forced displacement of Indigenous peoples.

Uganda is one such country. The current rate of 1.2C of warming is already causing devastating effects such as rapidly changing weather patterns like floods and drought.

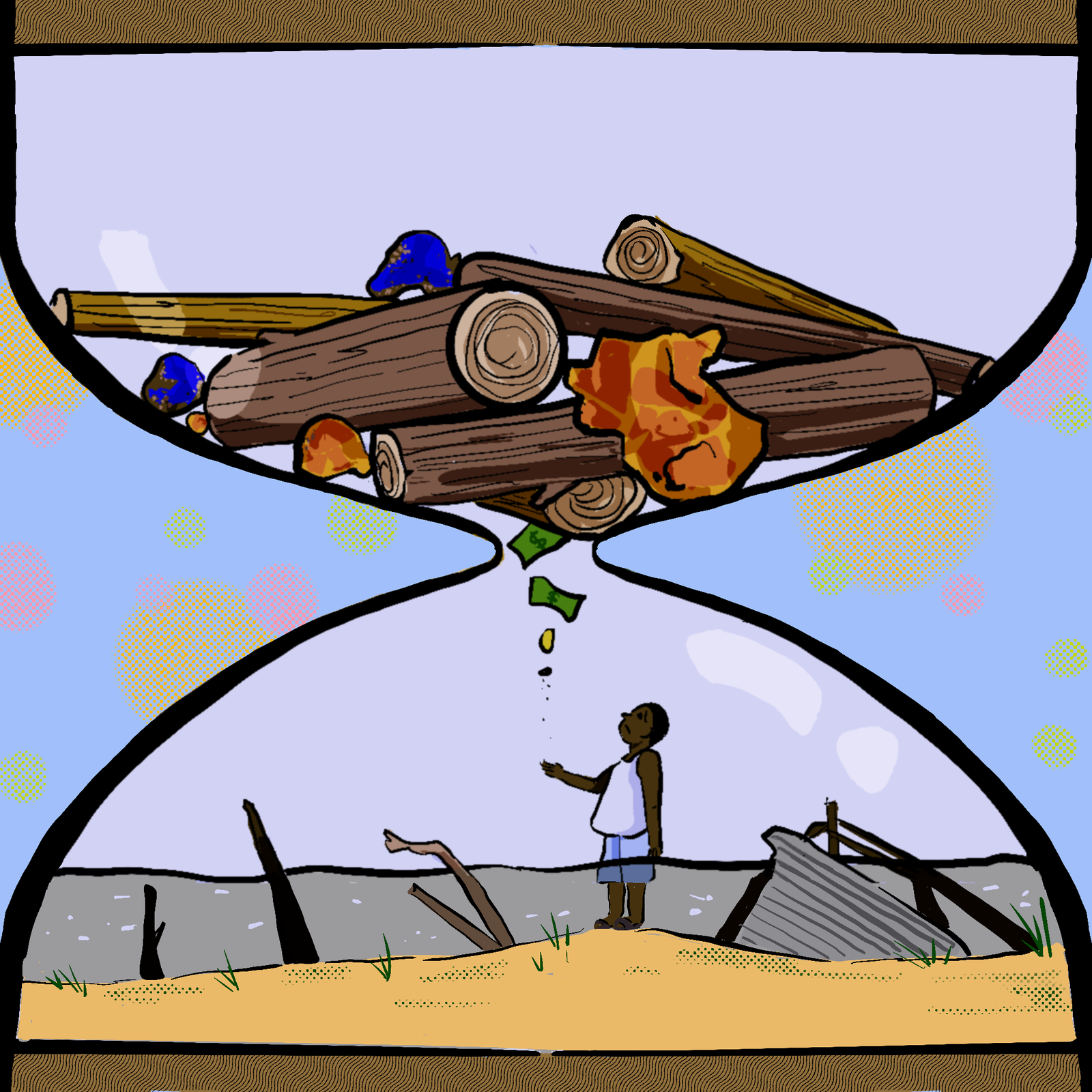

The impacts of deforestation and mining

The Southwestern and Western parts of Uganda are particularly at risk, warming faster than other regions, according to the Uganda National Meteorological Authority.

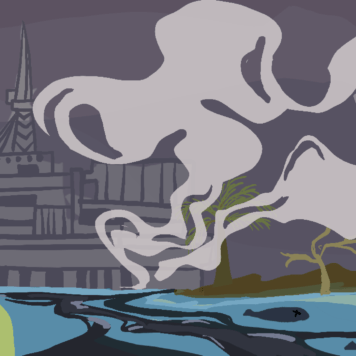

This is in part due to the heavy deforestation and mining in this area. Kasese, a region in Southwest Uganda, has borne the brunt of a joint venture by the Kilembe Mines Limited, a project started by two Canadian companies in the 1950s to extract copper and cobalt.

Over time, rivers became blocked through a process called silting where excess soil and stone fragments from the mines end up in local waterways. The result? A drastic change in the local land topography and consequently of the river courses.

This action, compounded by climate change, has led to frequent flooding and landslides in neighbouring villages throughout the year.

“Kasese used to have two predictable weather seasons: the wet season and the dry season,” says Crispus. “This binary has now become unpredictable and unreliable.”

Mount Rwenzori, a mountain range which sits on the border between Uganda and the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), is famous for its glaciers which source surrounding rivers and are responsible for providing neighbouring areas with water. But, increased global temperatures and deforestation has escalated the frequency of flooding and landslides, even in dry seasons.

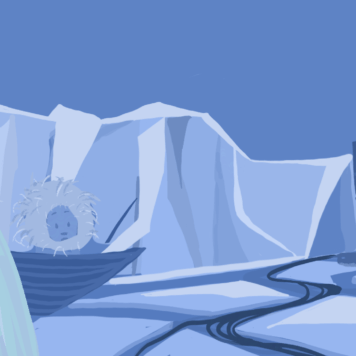

In the last two years, over 100,000 people have been displaced and eight people have died – not including the most recent floods. “These figures increase to 150,000 and 20 respectively when you assess the last nine years,” Crispus tells me – and there are now thousands of internally displaced people housed in refugee camps around the country.

Consequently, it is the people of Kasese who have been suffering. Many have lost their homes and lands and this has led to food insecurity and a loss of income, with women and children feeling this change in circumstance most keenly.

“Children have had to drop out of school because their families can no longer afford the fees and school materials, and many children now have to take up work to help provide for their families,” Crispus explains. “There have also been cases of parents selling off their female babies at birth for a dowry to sustain themselves and domestic violence has increased, especially amongst those living in the camps.”

Aside from the poverty-related social impacts that the flooding has on the Kasese community, there are also safety concerns for people living in the camps. Flooding can occur at literally any time, even on a sunny day when there has been no rain, meaning the infrastructure of the camp is at constant risk.

Despite all of this, the Ugandan government has failed to provide a strategic plan or response to climate change, and many feel abandoned in their own country.

A community response

So, how are the people responding and adapting to climate change in Uganda?

The Muhokya Camp Livelihood Project provides emergency support and a sustainable form of living to those who have suffered from the dual impacts of climate change and COVID-19. Hosting around 1,300 displaced individuals, the project aims to provide essentials like bedding, mosquito nets and educational materials.

They also want to teach the community skills like gardening and sewing, so people can support themselves in an environmentally friendly way.

Most importantly, they want to highlight the plight of those living in areas of Uganda who are being affected by the dual and interconnected impacts of the climate crisis and extraction.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

“We wanted to give a platform for people as they’ve not only been abandoned by the Ugandan government, but by international support organisations too,” explains Crispus.

Many of the internally displaced people living in the camps do not identify as refugees, but instead describe themselves as “Ugandans in Uganda who need help”, people who are being made to feel like “foreigners in their own country”.

Uganda is landlocked between several countries including South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda, many of which have seen a lot of conflict in recent decades.

Therefore, despite being one of the poorest countries in the world based on GDP, Uganda hosts some of the highest numbers of refugees in the world, strengthening the case that effective climate adaptation and mitigation strategies need to be put in place urgently.

However, no such action is being pursued on a large scale.

The forgotten nature of those residing within the camp was underlined during the COVID-19 pandemic. While the Ugandan government’s response to the pandemic was generally effective, with strict lockdowns and far-reaching vaccination schemes, those living in the camp were completely cut off from government aid.

This had previously included provisions like food, soap and salt, so, in addition to not receiving COVID-19 specific aid during the pandemic, what little help they had previously was taken away. Consequently, food poverty within the camp increased, and the fear of COVID-19, coupled with rising inflation, also meant that community support from outside the camp was scarce.

I asked Crispus what living in the camp is like. “Generally, life in the camp is very unlivable,” he tells me. “People live in poorly made houses, are hungry and lack safe drinking water.”

Residents also suffer from invisible afflictions with mental health conditions increasing, especially among single mothers. Namale Rehma, a widowed mother with 12 children and seven grandchildren has been living in Muhokye Camp since 7 June 2021. She was forced to flee her home after it became submerged and occupied by hippos, but before this, she says: “we had everything and were happy.”

“We will stand again”

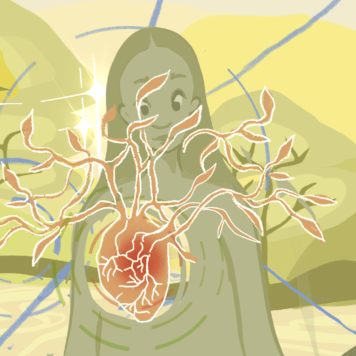

Despite these struggles, both the activists leading the Muhokya Camp Livelihood Project and those living at the camp have hope.

Crispus hopes that by “speaking out for (his) people and expressing their concerns, they will one day attract the attention and support that they deserve.” He continues: “seeing other young people in Uganda speaking out and spreading awareness about climate change also gives me hope.”

Community care, such as that provided by Crispus and his team, is vital for radical system change and climate adaptation strategies. Ironically, while underfunded and resource poor, these knowledge systems remain invaluable.

Those who are in positions of power would do best to sit up and take notice of the strategies being developed within their own borders to fight the climate crisis as they’ll soon be universally needed.

What can you do?

- Donate to the GoFundMe Page – the money will be used to acquire safer land and build permanent housing as well as to provide the essentials such as food, clean water and educational materials.

- Read more about climate justice in shado issue 03

- Follow Crispus here and the Abyuuti Community Group here

- Partner with Crispus and the Abyuuti Community Group to effectively impact the lives of those impacted by climate change and the pandemic in Western Uganda.

- Amplify the project on social media

- Learn more here, here or here