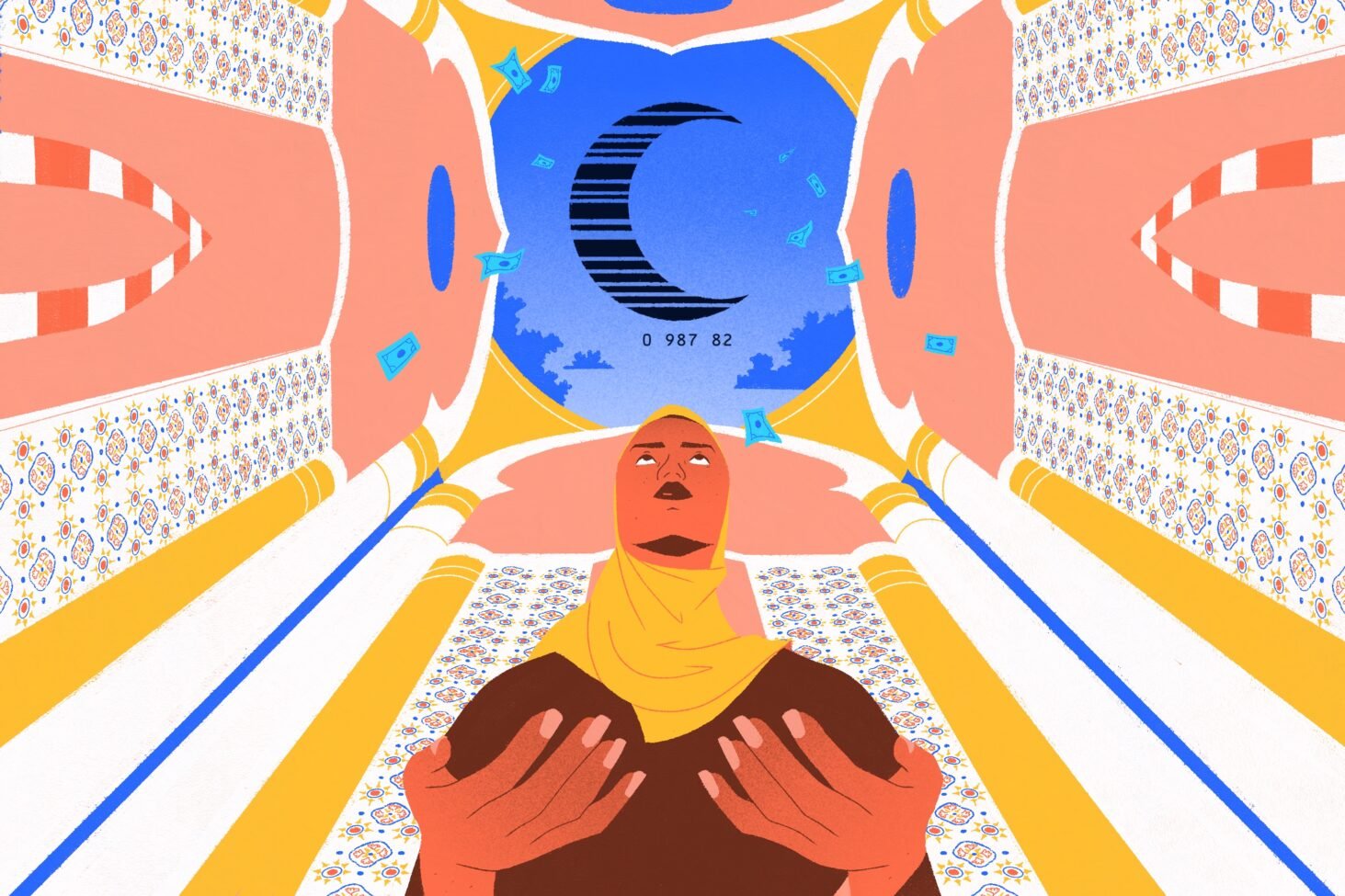

Walking through my local Tesco in London, I pause in the seasonal aisle. Something new catches my eye among the Easter chocolates and barbecue sets: paper plates and napkins adorned with “Ramadan Mubarak” in elegant gold script.

It’s a sight I never expected. Being new to London and having grown up in a European country with a relatively small Muslim population and significant state Islamophobia, I am used to Ramadan feeling almost invisible in public spaces. While I cherished the warmth of Ramadan within my small Muslim community, stepping outside that circle felt like entering a world where the holy month simply didn’t exist. Ramadan in London has proven to be quite different.

For a moment, I was tempted to buy those Ramadan Mubarak paper plates for the potluck iftar I was hosting that evening. But I quickly snapped out of it. I try to be mindful of my consumption and avoid buying things I don’t really need.

Like many Muslims worldwide, I’ve always been taught that Ramadan is more than just abstaining from food and drink from dawn till dusk; it’s about letting go of material attachments and pursuits, and redirecting the focus onto spiritual endeavors. It’s a time to draw closer to God and build better habits for the rest of the year. So, in that sense, Ramadan-themed paper plates and branded gift bags don’t quite align with the month’s essence, do they?

One thing about being hungry and an overthinker is that it gives you plenty of time to contemplate and reflect. And so, my walk home became the catalyst for this reflection on Ramadan and capitalism.

The commercialisation of Ramadan

Over the years, Ramadan has become a prime marketing opportunity, with brands eager to tap into new consumer bases. What once felt like a niche acknowledgment, perhaps a small “Ramadan Kareem” sign in a local shop window, has evolved into large-scale campaigns by global corporations.

We’ve seen Coca-Cola’s Ramadan advertisements reaching audiences worldwide, MAC’s “Get Ready With Me for Suhoor” tutorials, and Red Bull’s Ramadan-themed tweets. Some campaigns cater to specific markets, such as McDonald’s Singapore and Red Bull Nigeria, and tailor their messaging to Muslim-majority countries. At the same time, Western branches of these same corporations cautiously dip their toes into Ramadan-related marketing.

The irony runs deep: commodifying Ramadan for profit is one thing, using one hand to reach into the wallets of Muslim communities while wrapping the other around their necks. As they attempt to exploit the Muslim consumer base, they are also major contributors to environmental destruction and climate change – issues that disproportionately impact the Global South, many of whom are Muslim. Worse still, many of these companies are actively contributing to the genocide of Gaza’s predominantly Muslim population and appear on the BDS list.

This kind of surface-level recognition – often little more than a money-making ploy – can give the illusion of progress, leading us to believe that representation itself is enough. But rather than celebrating our inclusion in corporate marketing strategies, we should ask more profound questions. Isn’t this commercialisation, which encourages more consumption, fundamentally at odds with the spirit of Ramadan?

I fear that a month centered on discipline, restraint, and spiritual reflection is now being repackaged as a sales opportunity – turning an act of devotion into just another seasonal trend.

What is Ramadan?

Fasting is prescribed across various faiths, each with its rituals and significance, reflecting diverse spiritual paths and interpretations. Fasting is one of the five pillars of Islam and is prescribed during the holy month of Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar. This month holds great significance as it marks when the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) first received the revelations of the Qur’an.

For 2 billion Muslims worldwide, Ramadan is a month of fasting (for those who meet the physical and psychological conditions to do so), prayer, self-improvement, and increased acts of worship.

From dawn to dusk, Muslims refrain from food and drink. Throughout the month, Muslims increase their worship, and strive to improve their character by shedding bad habits and strengthening good ones. Central to this month is a deeper connection with the Qur’an and a renewed commitment to faith.

More than just a religious obligation, Ramadan serves as a profound reset, an opportunity to step back from the noise of daily life and realign priorities.

Ramadan as resistance to capitalism

Most Muslims you meet will eagerly express their excitement for Ramadan’s arrival, a sentiment that may surprise those unfamiliar with the month’s significance or struggle to see the excitement about being deprived of food and water.

At its core, Ramadan teaches detachment from worldly and material affairs. It is a conscious decision to abstain from ordinarily permissible – food, drink, and other comforts – embracing hunger and thirst as part of a greater spiritual discipline. This would suggest that Ramadan is, by nature, the most anti-consumerist and anti-materialist month. It reveals a striking truth: we need far less than we think to thrive. Stripping away excess can bring clarity, peace, and a renewed sense of purpose.

Capitalism demands constant efficiency, pushing people to maximise output at all costs, equating success with material gain and worldly achievements. But Ramadan shifts that definition entirely: it forces a slowdown.

The physical toll of fasting naturally reduces energy, encouraging rest, reflection, and focusing on the spiritual over the material. Success is no longer measured by productivity or financial growth but by self-discipline, inner peace, and closeness to God. It is a reminder that the ultimate goal is not accumulation in this world, but fulfillment in the next. This directly contradicts the capitalist mindset, which insists that one’s worth is tied to their ability to produce and consume.

Where capitalism thrives on individualism, Ramadan strengthens community. Fasting is not just an act of personal discipline. It is a direct, physical experience of deprivation. By willingly going without food and drink, even for a limited time, you place yourself in the position of those with no choice. There is perhaps no more powerful way to build solidarity than to feel, even for a fraction of the day, what some of the most vulnerable experience daily.

This empathy drives the core of Ramadan’s emphasis on charity and collective responsibility. While capitalism encourages competition and self-interest, Ramadan insists that true success lies in generosity, uplifting others, and understanding that no one thrives alone.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

On top of the third pillar of Islam being giving a fixed rate of one’s wealth to charity, Ramadan concludes with a supplementary obligatory charity, known as Zakat al-Fitr, which those who meet certain conditions must give to those in need within the community before the month’s end. This further highlights that Ramadan is not just about personal reflection but also about fostering community and mutual aid – an antidote to the culture of greed and exploitation that prioritises wealth accumulation at the expense of others.

Ramadan and revolution

Beyond fostering community and solidarity, Ramadan has been a powerful catalyst for social progress and revolutionary action. Throughout Islamic history, the strength of this holy month has been demonstrated in the triumphs of early Muslims, who overcame overwhelming odds in battles where they were vastly outnumbered.

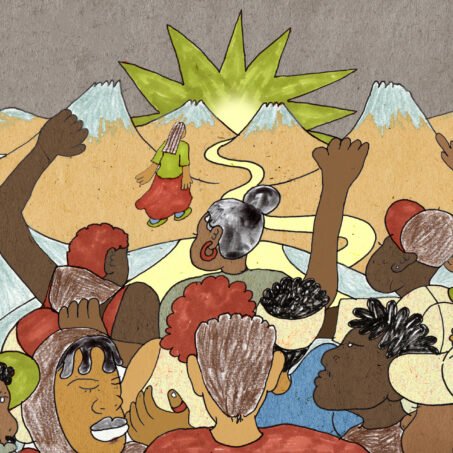

Over the centuries, Muslims have continued to harness the transformative power of Ramadan, fasting in diverse and challenging environments, from enduring slavery in the Americas to fighting wars of liberation in Algeria and Bangladesh to withstanding the ongoing genocide in Palestine today. A lesser-known yet powerful example of Ramadan’s revolutionary spirit is the 1835 Malê Revolt, also called the Ramadan Revolt, in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil.

Brazil, home to the largest African diaspora outside Africa, has a deep Islamic history, particularly in Bahia, the centre of the slave trade. Many enslaved West Africans, despite coming from different ethnicities such as Mandinka, Yoruba, and Hausa, were united by their Islamic faith and Arabic knowledge. Despite oppression under the Portuguese Empire, they maintained strong religious practices, often covertly, establishing places of worship and Qur’an schools and keeping up with Islamic duties such as fasting. Between 1816 and 1830, Bahia’s enslaved community organised 17 uprisings, with the Ramadan Revolt being the most significant.

On Sunday 25th January 1835, in Salvador da Bahia, over 600 enslaved people of West African origin rose against their Portuguese slave masters. The rebellion was strategically planned by the majority Muslim enslaved population, not only to coincide with the last ten days of Ramadan – a period of immense spiritual significance – but also to take place on the 27th of Ramadan in the Islamic year 1250, a night widely believed to be Laylat al-Qadr, the Night of Power.

Laylat al-Qadr holds deep spiritual meaning for Muslims, as it marks when the Qur’an was first revealed to the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). It is also known as the Night of Decree, when the upcoming year’s events are ordained. Muslims believe in predetermination – that our fate is written – and while the religious details are intricate, the significance lies in understanding that this night holds immense power.

On Laylat al-Qadr, one’s influence over the year ahead is believed to be at its strongest, with a heightened capacity to shape what unfolds through supplication and prayer – from life’s blessings and hardships to even whether your life will end that year. Acts of worship and good deeds hold high on this night and carry even greater weight. The Malê Revolt, strategically planned for this powerful night, reflects the profound connection between faith and resistance, as the enslaved Muslims drew on the spiritual power of the holy night to fuel their fight for freedom and write a future of liberation and justice.

The rebels attempted to raid a prison to free their religious leader, Pacífico Licutan, and attacked a military barracks guarding the city. Outnumbered and poorly armed, they were defeated. 80 rebels were killed, 45 publicly flogged, and over 500 Muslim Africans, including many of the rebels, were deported to Africa.

Despite its failure, the Malê Rebellion is a turning point in Brazil’s history. Following the revolt, Portuguese slave owners were given six months to baptise enslaved people and provide religious education or face fines for each non-Christian they owned. Historical records detail the community, key figures in the revolt, and archival materials such as handwritten Qur’an verses that rebels carried for protection. By the 1850s, the transatlantic slave trade to Brazil began to decline. The 1871 “Free Womb Law” declared children born to enslaved mothers free, and slavery was formally abolished in Brazil in 1888.

This stands as a powerful example of the deep connection between anticolonial resistance and spirituality, showcasing the revolutionary strength of Ramadan. Throughout history, in even the most challenging conditions, Muslims have drawn on this spiritual power in their unwavering pursuit of justice and bettering themselves.

What’s the takeaway?

No one is saying you can’t buy a festive treat or decorate your home to welcome the month. Muslims around the world have long embraced these traditions. But when major corporations jump on the Ramadan bandwagon, it’s worth asking: who is this really for?

The aggressive commodification of a month rooted in spiritual detachment highlights just how little these brands understand the Muslim community beyond the size of their wallets. While Islam has its unique financial system, Ramadan inherently opposes capitalist ideals of overconsumption, profit maximisation, and the relentless emphasis on worldly productivity. Instead, championing community, balance, and intentional spending. These values aren’t just for the month; they are embedded in Islam year-round, with the Qur’an warning against miserliness but also against frivolous spending and unchecked excess.

In the end, I walked away without Ramadan-themed paper plates. Still, I gained something far more valuable: a deeper appreciation for the month, a renewed commitment to rejecting hyper-consumption and waste, a sharper awareness of how corporations will always find a way to turn faith into a marketing strategy, and a reminder of the revolutionary histories that shape Ramadan’s true meaning.

What can you do?

- Whether you fast or not, increase your understanding of fasting in different belief systems and try it out. Take inspiration from Ramadan by dedicating time to consciously step back from consumption, not just of products but of media entertainment. It is about filtering what you put in your body, whether it be through your mouth, eyes, or ears. Reflect on your habits, critique your spending patterns, and observe how this shift impacts your life.

- Approach surface-level inclusivity with a critical lens. Ask yourself why these ads are being created – are they driven by genuine understanding or simply a strategy to maximise profit?

- Delve deeper into the revolutionary aspects of Ramadan, both as a religious practice and through its historical significance for the communities that have observed it.

- Listen to or watch the recent episode of The Thinking Muslim Podcast: Ramadan: The Radical Reset for a Capitalist World – with Imam Tom Facchine

- Read more about the history of Muslim communities in the Americas:

- Explore the concept of mutual aid in Islam, particularly through Zakat, and consider how the world might be transformed if more people gave a fixed percentage of their wealth to those in need. A good read on this is “Zakat is not just Charity: Unlocking the Transformative Power of Islam’s Third Pillar”