In June 2022, Pakistan experienced some of the heaviest monsoon rainfall it has ever seen, not long after record temperatures of 51C hit the country earlier in the year.

The floods are continuing to rage on at the time of writing, with an estimated 1300 deaths and 33 million people displaced.

Emergency food rations, medical supplies, shelter kits and tents are slowly making their way into the country, and some are temporarily seeking refuge in abandoned buildings.

And it’s not just their houses and belongings that have been washed away – for many, it’s also memory-laden ancestral land, which has been home to several generations before them.

As environmental rights activist Ayisha Siddiqa has highlighted: “It will never be the same, the soil will not be the same, the seed will not grow the same. It is beyond material loss, it’s spiritual and emotional. The land is in pain, we feel it too.”

This is a story that will continue to repeat itself as climate disasters become increasingly common, particularly in regions that have been systematically stripped of the finances and resources to be able to defend themselves, and where land ownership is still a key financial and community asset.

In a lot of countries in the Global South, owning land is not only the key to home ownership, but also to subsistence farming – in other words, a means to feed yourself and your family. Land is often passed down through generations, and with the climate crisis putting this at risk, entire families’ generational assets are suddenly at risk too.

Earlier this year, Tropical Storm Megi swept through the Philippines, displacing around 800,000 people. Landslides and flooding in some urban areas of Brazil have caused another 70,000 people to be separated from their homes. An estimated million people have been displaced by severe droughts in Somalia.

There are a number of overlapping issues at play here. Where, firstly, do displaced people go, particularly when infrastructure around them is crumbling? How does this increase in climate refugees marry up to incredibly restrictive and hostile immigration policies in developed, resource-rich nations? Are loss and damage budgets sufficient enough to rebuild housing for the displaced – housing that is resilient and adaptable to changing weather patterns, and financially accessible?

In a capitalist system, all of these issues intersect and overlap. The climate crisis leads to housing precarity, while the resulting increase in displaced peoples collides with nationalist, anti-immigrant sentiment in the West.

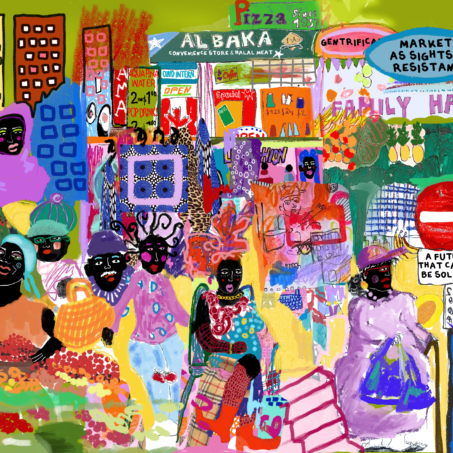

State ignorance and gentrification continue to exacerbate the problem for those at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder, such as short-term renters, the houseless and homeless, and refugees and asylum-seekers. All of these intersecting issues provide the backdrop within which the Radical Housing Journal conducts its research.

Campaigning for housing justice

Founded in 2016, the Radical Housing Journal is made up of a group of multidisciplinary researchers and scholar-activists, including Samantha Thompson, Ana Vilenica, Felicia Berryessa-Erich, Mara Ferreri and Michele Lancione, who are spread between Latin America, North America, Europe and Asia.

Having read some of the Journal’s brilliant pieces – some of which have recently centred on the links between housing struggle and abolition, and state protection of the rental market – we caught up with the team over email.

With seven issues published so far, the focus of the journal is on macro trends in the context of housing struggles. “Housing justice is an intersectional struggle that accounts for the ways that housing systems uphold and reproduce structures of power, like those shaped by racial capitalism, colonialism, imperialism and cis-heteropatriarchy,” they say. “Housing justice means ensuring that everyone has access to housing that supports their needs, but also seeks to dismantle these systems that produce housing injustice in the first place.”

More and more people find themselves at the whim of a system that marketises and financialises housing, rather than treating it as a fundamental human right. Where the demand for housing outstrips supply – as it does in most urban environments – landlords can get away with charging exorbitant amounts of money for relatively low-quality housing. This not only has the obvious effect of deepening socioeconomic inequality, but also has massive implications for physical wellbeing, mental health, and families’ abilities to stay together in housing that works for them.

The Journal’s first edition focused on a crisis that exposed the deep-seated links between stable housing and the economy: the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007 and 2008, in which homebuyers from low-income backgrounds were offered extremely risky loans. “Our first issue focused on post-2008 as a field of action and inquiry in uneven housing justice struggles,” they add. “In this issue, we took the 2008 subprime mortgage and financial crisis as a global event that impacted cities, suburbs and rural spaces highly unevenly, requiring a nuanced understanding of that particular moment and an openness to analyse its repercussions.”

And over the last two years, it has become impossible to separate the pandemic and “stay-at-home” orders from what it means to have a house and a home in the first place – which also rings true for climate-induced displacement.

“In our collectively written article ‘Covid-19 and housing struggles’, we argued that big catastrophes often work to speed up everyday political and economical disasters, and exacerbate existing inequalities and injustices. We wrote about lessons from climate disasters such as Hurricane Maria across the Caribbean that have shown how disaster management produces state failure, social abandonment, capitalisation on human mystery, and collective trauma.”

Through their research, the Radical Housing Journal has not only uncovered links between the climate crisis and housing insecurity, but also race and class struggle, particularly in places like Jakarta and Lagos.

“We’ve carried out a number of interviews where housing organisers from several locales across the globe have routinely brought up the entanglement of housing and environmental struggle. This is done not only at the level of thinking and doing more climate-resilient housing, but also [on the level] of challenging how many local and national authorities are using environmental hazards as a tool to displace communities, promulgate whitening urban developments, and reproduce forms of racial dispossession.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

In other words, ‘just housing’ is much more than just the physical structure of a home itself: it’s about where that home is, its long-term viability and resilience, what ‘community’ looks and feels like, access to green space and amenities, and affordability beyond property ownership.

The act of ‘placemaking’ goes some way to addressing this need for community-centric housing and urban planning strategies. The city of Pontevedra in Spain hosted a four-day long placemaking festival in September, which focuses on collaborative and participative approaches to designing cities.

Housing and community care

But, the group says, large-scale incidents such as the pandemic and natural disasters also open up the floodgates to solutions and radical ways of approaching our housing needs.

“These scenarios include mutual-aid bridges that emerge from both new and existing solidarity structures, infrastructures such as public kitchens, and the occupation of abandoned spaces for housing and organising, with long term effects for the distribution of energy, food and knowledge,” they say, adding examples such as rent strikes and community land trusts, nonprofits that buy and develop land for the explicit benefit and needs of the local community.

Property ownership has, in many parts of the world, become a privilege afforded to the few at the expense of the many, a divide that only becomes more prominent as the economics tip ever more in the favour of landlords.

Radical and just housing therefore not only has to factor in the safety and security of renters, but also the widespread adoption of alternative ways of living and making a home.

That could be property guardianship, shared care networks beyond the nuclear family unit, and increasing accessibility to land ownership, which can allow people to build homes and self-sufficiency structures in a way that suits their needs.

Halton Mill, a housing and coworking development in the North West of England. Recreated out of an old and disused industrial building, Halton Mill is committed to providing energy effective homes – of which it has 41 today. That includes a community-based hydro power scheme, which has allowed the community to transition to being fully powered by renewable energy.

In this way, developments such as Halton Mill prove that just housing is much more than the shell of a home itself – it also factors in different models of ownership for utilities, food supplies and green space.

Housing is both personal and deeply political. It’s also vulnerable, be that due to a volatile market or the climate crisis. Between all of that chaos, giving individuals, families and communities the right to define what a home looks like for them can provide a small sense of hope and control.

What can you do?

To learn more about housing justice and struggles, here are a handful of resources:

- Read Tenants by Vicky Spratt, a brand new journalistic account of housing struggle in the UK. It recounts the steep decline of home ownership in the country — coupled with the sharp increase in renting – and the political decisions that got us here.

- Follow a local renter’s union. You can find them in a number of cities, particularly where there is a huge income disparity. For instance, the Tenants Union of Washington State provides education and advocacy for tenants’ rights.

- Research what precarious housing looks like in the fastest-growing cities of Africa, such as Nairobi, Lagos and Addis Ababa. This research project from 2017-2018 was undertaken by the London School of Economics and weighs up rapid urbanisation in these cities with socioeconomic inequality that is exacerbated by market forces.