I have lived in South London all my life. It’s my hometown glory, my claim to fame and my proudest personality trait. I get my flair, zest for life, passion for culture, music, heritage and history from this space. It raised me, my friends, my family, my neighbours and some of my icons.

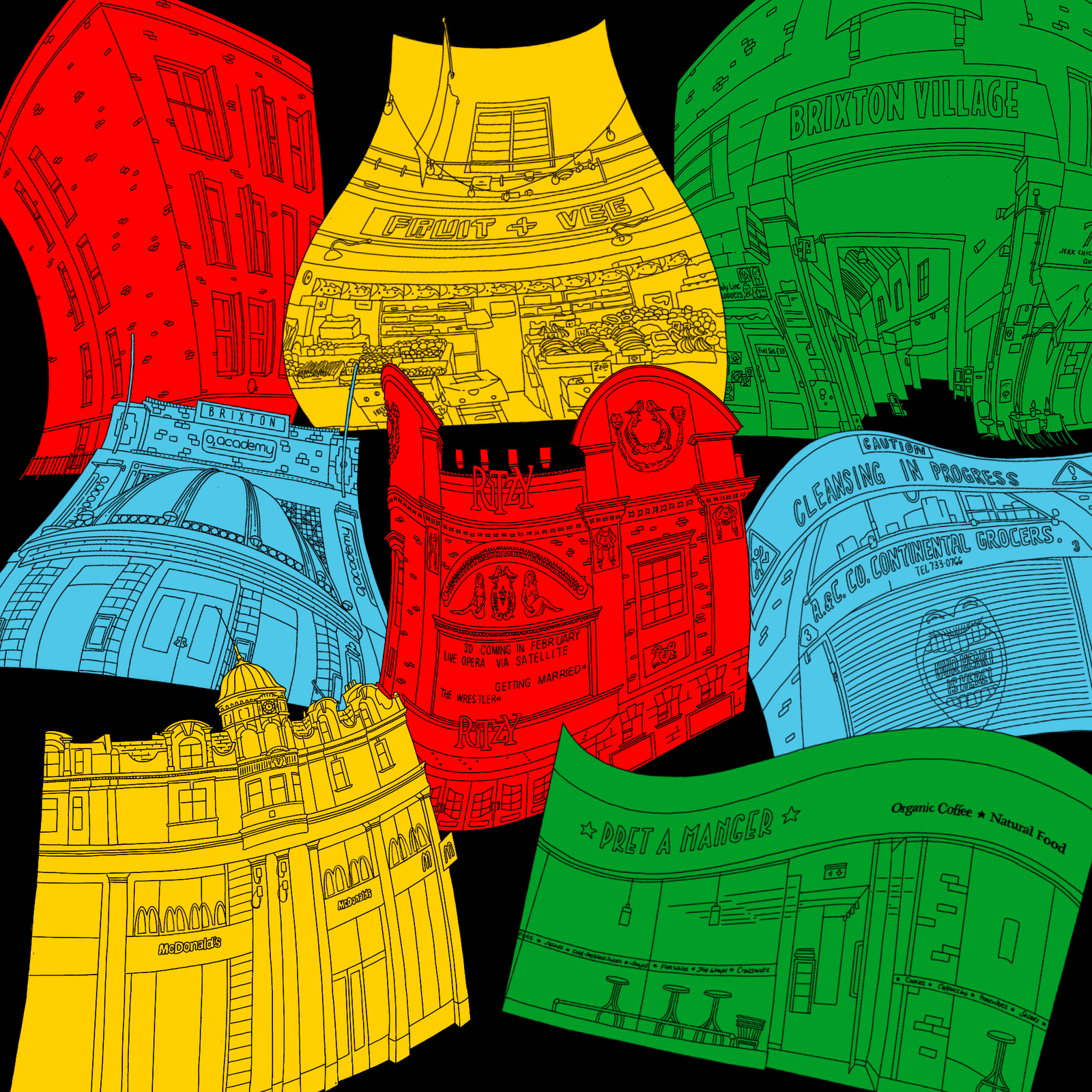

My pride for being a South Londoner runs deeper because I’m from Brixton. Known for its vibrant, multicultural and insurgent vibe – it’s a reflection of the history of communities that live there. In particular, its Afro-Caribbean community who settled between Clapham Common and Brixton when arriving on the SS Windrush.

Walking through Brixton, there’s a certain ‘aliveness’ to the place you don’t get everywhere. From the bustling market, to the legendary 24 hour Brixton McDonalds, to its nightlife, to its preachers of all faiths lining up on Brixton Road trying to beckon you in, there’s never a dull moment here.

It’s also historically been home to many queer, Anarchist, Black, Brown and feminist individuals and movements. There were the 1981 Brixton riots, Nelson Mandela’s anti apartheid visit, Olive Morris, OWAAD; and Railton Road was a hub for many organisers. Brixton’s cultural, political and social history has always been rooted in community, resistance and international solidarity, particularly against state violence and repression.

Brixton: Is my area changing?

Like many London neighbourhoods though, Brixton is changing. It’s changing in ways I could have never imagined and faster than what feels stoppable.

People, spaces, places are going missing, never to be spoken about again. Replaced overnight, like they were never part of the community. My neighbours are leaving; shops, community centres, play centres, parks and public spaces are all being wiped off the map.

When I was a kid, I went to Durand Primary School in Brixton’s Cowley Estate. I distinctly remember walking through a large grassy field with rolling hills with my older brother to get to school. That’s gone now. In its place, a new luxury residential development pleasantly named Oval Quarter, complete with unaffordable rents, is built over the majority of the green space. Just like that, a huge aspect of my childhood has disappeared without a trace.

What does it mean when you experience loss and have nothing to show for it? How can we describe these spaces to our kids and younger generations, with them only able to visualise this through our memories and photos?

This is what Brixton and many neighbourhoods in London are up against. What these neighbourhoods have in common is that they are characterised by a large population of working class people, migrants and people of colour.

There is often low investment in the area and its infrastructure: usually fewer green spaces, or at least poorly maintained; overstretched schools; underfunded hospitals and roads. There is a historically high proportion of social housing and often well interconnected communities and amenities like shops, community hubs and spaces.

These spaces often hold the city’s zest, creativity and socio-cultural capital. They’re also often well connected transport wise, making them very attractive to developers and investors. To these developers, there is no care for the people, cultures, space or landscape. These things are simply collateral damage in the pursuit of profit.

The violence of gentrification

There’s a running joke that if a Pret, Leon, Itsu, independent coffee shop or “traditional” barber shop hits your area, gentrification is well on the way. It’s hilarious because it’s the same rollout in every neighbourhood and everyone can spot it from a mile away. Funnily enough, Brixton now actually has all of these: all on the same street, in fact.

The formula never changes and the results are predictable to say the least. Incoming: manicured patch grass, high rises made of glass, soulless ‘perfect’ neighbourhoods and a food court of some sort. We don’t need to look further than Elephant & Castle’s ‘Elephant Park,’ developed by Lendlease and its displacement of the predominantly Black and Latinx community along the way – to see this in action.

Unfortunately, it’s a running joke that has more insidious consequences. In Brixton, this has led to independent traders from the Brixton Arches, many of whom had been there since the 90s, being priced out of their spaces to make room for flashier chain restaurants and shops that cater to new Brixton audiences.

The violence of gentrification looks like hostile architecture in the form of single seat benches in Windrush Square. Making the streets unlivable for people who are street homeless doesn’t get rid of homelessness –safe, affordable housing does. Brixton has an incredible independent food scene, many family run businesses, now in competition with chain restaurants that are half as good in flavour and double the price.

Policing and police presence has always been an issue in Brixton due to its population of Black and working class people. However, there’s been a steady increase in police presence and policing of Black people, particularly the youth.

This has led to more racially motivated stop-and-searches, harassment from the police and the shutting down of community-led events and gatherings. Night sound systems shut down, Brixton Splash shut down, and protests against these were heavily policed.

Who is Brixton for?

Brixton’s vibrant culture has been used by estate agents and developers to brand Brixton as the next place to move to increase their profits.

In Nabil Al-Kinanis book Privatise The Mandem, he takes an advert from an estate agent about Angell Town estate in Brixton, which has been described as a ‘no go zone’ in the press since the 80s. The advert now describes the estate as “in zone 2 of TFL, access to overground, Victoria and Northern line, within a one mile radius of Max Roach park, two mile radius of clapham common park, 14 primary schools in one mile radius, near oval cricket ground and a booming nightlife with Electric Brixton, the O2 academy and more…”

The newbuild houses are unaffordable and clearly not catering to the working class locals, rather, ushering in new middle and creative classes who are pushing out people who can no longer afford to live here.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

The whole demographic of Brixton is changing as a result. Most ironically, Olive Morris House, Lambeth council building and housing office and a huge support for the local community, named after Olive Morris, a radical feminist organiser, Black nationalist and housing and squatters rights campaigner from Brixton was demolished over lockdown. In its place it boasts a 40% ‘affordable’ flats being erected, where a minimum payment of £155,000 will buy you just a 25% share of a two bed flat. The jokes are writing themselves and the consequences are far from funny.

Watching your neighbourhood change in unrecognisable ways that are clearly in no way beneficial for the locals is devastating. It has left me feeling powerless and hopeless.

As people, particularly in the UK, we are taught from an early age that our power and agency doesn’t belong to us. We are encouraged to be passive, individualistic and unresponsive in the face of violence and injustice. But we cannot stand by and watch all the areas, estates and community hubs we’ve ever known and loved get taken away from us.

They cannot take our homes away, they cannot gut the city from the inside out. Gentrification is a self-eating machine that will stop at nothing until our homes, our city, the blocks we’ve ever known and loved are a distant memory. It is only when we collectively fight back, that justice can be achieved.

What resistance has taken place in Brixton?

Nour Cash’n’Carry, a shop in Brixton Market set up by Aslam Shaheen in 2001, has been providing food staples for a multicultural neighbourhood for more than 20 years.

In 2020, the beloved shop was threatened with eviction by Taylor McWilliams of Hondo Enterprises, the market’s new millionaire landlord.

Brixton is known for stepping out for its community, and the reaction was no different. The Save Nour campaign was formed, a petition was created with thousands of signatures addressed to Taylor McWilliams, £10,000 was raised within a day of the fundraiser being released and this turned into £20,000 in the following days.

Thanks to the relentless campaigning and organising by the local community, as well as the viral videos sharing their heartfelt connection to Save Nour and Brixton Market it was made impossible for McWilliams to not know how the locals felt. The power of this campaign forced Lambeth council to denounce the eviction, who were initially silent on the issue. By June of that same year, plans to evict Save Nour were dropped in a monumental win for Shaheen’s family and the Brixton locals.

Fight the power, Fight Hondo Tower

Unfortunately, this wasn’t the end. Soon after the incredible Save Nour win, McWilliams wanted to erect a 20-story office building, dubbed Hondo Tower, in the heart of Brixton. Lambeth council initially waved through the development at a planning application committee in December 2020, despite Hondo’s own public consultation which found that 73% of local people opposed the scheme. A further petition launched against the tower raised almost 8,000 objections including Labour’s Bell Ribeiro-Addy and Helen Hayes.

This is when the #FightTheTower campaign began. Locals opposed this tower because it would displace the heritage, culture and people who live in Brixton, in particular its Afro-Caribbean community. The building would have been an eyesore and looked incredibly out of place against Brixton’s skyline.

Building an office block in an area that has been largely affected by gentrification and a suffering housing crisis where the average wait for social housing is over 10 years is criminal. It tells you exactly how far removed these millionaire landlords and developers are from the real struggle of housing in London. In fact, they don’t care. This apathy towards Brixton and its residents didn’t go unnoticed by the locals and once again, they got to organising.

This time, locals mobilised on social media, worked with other local groups, organised Zoom meetings, printed posters and leaflets and ran a weekly stall in Pope’s Road. They fundraised to undertake legal action. They provided guidance for objections on why the tower would harm Brixton, and hassled relevant authorities with petitions, postcards and rallies.

Then, after two cancelled hearings, McWilliams withdrew planning applications for the tower in July 2023.

This campaign was not only a fight against Hondo tower, but a fight against one man’s monopolisation of our beloved neighbourhood. What I loved about it was that it was a continuation of the Save Nour campaign.

What do we learn from resistance?

We can use all the connections, tactics and people-built networks we have to make bigger demands. It tells us that when we win our fight, we should turn to larger fights and disputes on our doorstep.

Something I also loved about this campaign is the celebrations that followed. Long term struggles against powerful property developers, local councils and our own government are designed to wear you down. Whether its intricate bureaucracy to simply shutting down attempts to organise or intentional union busting, the will to flatten resistance is always there.

That’s why it’s important to celebrate the wins we do obtain and recognise the group efforts to get there. In Brixton, there’s no other way to celebrate the shift of power than a street party exactly where the Hondo Tower was set to be built. That’s my kind of sesh.

Social housing, particularly in estates, have been under attack since the start of austerity. Labelled as ‘crime breeding’, socio-economically impoverished spaces by the media and politicians, this makes it easier to convince the general public that these blocks shouldn’t be there and in essence, the people that live there too.

This has made it easier for ‘regeneration’ projects to take hold that seek to displace entire communities, families, neighbours of the like. What they fail to mention is that systemic poverty stems from state failings rather than individual failings.

Over this same amount of time, we have seen the government pull back from state school funding, healthcare funding, childcare and disability benefits, shut down youth and community centres and take away opportunities for people – particularly young people – to learn vocations and secure employment.

In that same breath, local councils, as landlords, have allowed the managed declines of many social housing estates across London, leaving them in deep disrepair. These then become targets of gentrification as local councils take the ‘out of sight, out of mind’ approach, giving way for private investors to buy the land of estates rather than retrofit and repair these buildings, saving these estates and the hundreds, sometimes thousands of people that live in them.

Ongoing struggles like that of Milford Towers in Catford, Aylesbury Estate in Southwark and, prior to demolition, Heygate Estate in Elephant and Castle, show us that local councils play a very active role in the degeneration of these estates. We have to think, when they move these people out, who are they moving in? Who actually has rights to the city, our neighbourhoods, our blocks?

Social Cleansing: Who bears the cost?

This is exactly what happened at The Guinness Trust’s Loughborough Park Estate and Thrayle House of Stockwell Park Estate in Brixton. In both examples, we see working class tenants – often Black and brown women and families living in flats in terrible disrepair – re-offered assured short-term tenancy contracts in the lead up to eviction and demolition, but they were never supported with rehousing. In both cases, while promised more social housing being built, the number of social housing flats offered was actually less than what was provided in its original buildings.

Most tenants have been dispersed across London as far as Twickenham and Dagenham – extremely far from their immediate communities. This is because they were often told by Lambeth council to wait on their extensive social housing list (10 years long) or rent privately, opening them up to more disrepair and housing insecurity in the unregulated private renters sector. Being working class in the private renters sectors leaves you extremely vulnerable to poor housing and rogue landlords because you are less likely to have the financial means to afford safe and secure housing.

The people who move in are often white, wealthier people who can afford these private rents. That sets the precedent for what rent pricing should be in Brixton – which continuously goes up.

It’s only a matter of time before the majority of locals are completely priced out. It is more devastating because we know the standard of the houses prior to demolition would never be offered to the new tenants. Proper regeneration would see the old tenants rehoused in these new buildings at an affordable council rent. Gentrification is what is happening, it is fuelled by our privatised housing market, complicit government and local councils. Higher rents and displacement are a consequence of this.

Where is the hope in housing?

When I’m in despair about the world, or in this case, my city, it is people and community organising that shows me things can be different. It is the organising that happens within life’s limits and societal structures that show me the impossible is possible. It is the organising that happens amongst care responsibilities, raising children, health issues, grief, working multiple jobs that shows me the persistent need for dedication, care and diligence within our communities.

The need to see ourselves in each other’s struggles and each other’s revolutionary horizons is a promise to hold each other just that little bit closer because the world is bleak enough. It is a promise to learn the invaluable lessons of relating to each other, connecting to each other, muddling through together, conflict resolution and making space for each other that is only done by being involved in political struggle and ultimately, the desire for a better collective result.

When we turn the fight from a personal displacement to a fight for our blocks, our neighbourhoods, schools and parks – we realise it’s a fight for so much more. A fight against gentrification is a fight for our rights to the city, space and place. It is a fight against state sanctioned social cleansing. Our homes, our neighbours, our communities are not for sale.

What can you do?

Personal reflections on Brixton: No matter what, Brixton will always be my pride and joy. From the Speedy Noodle (RIP, but also this was food poisoning central), to going to Brixton market to snap the tops off of okra for soup later, to grabbing a patty from healthy eaters or Morleys (arguably the best one in south) after school, to me spending my evenings with my dad and brothers in Brixton Library, to me going to my first ever concert at the Brixton Academy (it was wiz Khalifa), to me going to my first ever anti-police demo outside brixton police station at 13, to all my friends from Max roach youth club (max roach to the world) , to dub and reggae blazing through speakers every day, to Brixton splash (RIP), to waving off all my friends in secondary school when we all part ways at Brixton to our homes, to the legendary skate park, to swimming lessons at Brixton recreation centre, to house parties blazing Sneakbo, ard adz and youngs teflon, these are the memories i’ll hold forever. There isn’t anything more special than growing up somewhere with a community and that feels like home. The recommendations listed below give you a small insight into why I love this place so much. I hope you enjoy them as much as I do.

Articles

- Brixton Gentrification Struggles 1993-2021: A Timeline (maydayrooms.org)

- Save Nour campaign to help Brixton food shop is gaining strength (timeout.com)

- The heart of Brixton ripped out as traders are evicted from the Brixton Arches (brixtonbuzz.com)

- Lambeth Hidden Stories: Dora Boatemah – Black Thrive – Lambeth

- The Tale of the City: Gentrification in London – Part 2 – UNICORN RIOT

- Today in London squatting history, 1969: Brixton’s first squatters? Empty offices occupied. – LONDON RADICAL HISTORIES (pasttense.co.uk)

- Radical Histories of Railton Road Mural – Summer 2021 – Jacob V Joyce (radiant-minds.co.uk)

- The Brixton Arches businesses caught in London’s tide of regeneration – in pictures | Cities | The Guardian

- Reggae, riots and resistance: the sounds of Black Britain in 1981 (pan-african-music.com)

- Do you remember the day that Mandela came to Brixton? (brixtonbuzz.com)

- Guinness Trust: The Loughborough Estate Occupation – architectsforsocialhousing

- Guinness Partnership defers eviction of Brixton social housing tenant | Social housing | The Guardian

- In photos: a deserted Stockwell Skate Park and its new luxury development neighbour, Sept 2020 (brixtonbuzz.com)

Films

- Babylon (1980) : Franco Rosso : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

- Official Documentary: The Battle For Brixton April 1981 – YouTube

- Brixton Belongs To Me | Welcome to Together TV | Together for good

Documentaries

- We The People | Museum of London

- Brixton…Is Your Area Changing? (S1, E1) – YouTube

- Uprooted fully release online! — Ross Domoney (ross-domoney.com)

- Brixton: Flames on the frontline – this is actually a podcast hosted by brixton’s very own Big Narstie. He narrates what led up to the 1981 Brixton Riots

- Guinness Trust abandons Brixton resident to live in Limbo – YouTube

Places to visit

- Black Cultural Archives – They collect, preserve and celebrate the histories of people of African and Caribbean descent in the UK – it’s incredible

- Brixton Market and village for fresh produce and food from independent owners.

- About – brixtoncommunitycinema

- Supertone Records – Black owned record store

-

Brixton Library – make sure you get a Library card!

Songs

- SNEAKBO, POLITICAL PEAK & JJ – TOUCH AH BUTTON – YouTube – my favourite song, a timeless classic by Brixton native Sneakbo, filmed in Angell town Brixton. Other classics include Sneaky & Chrissy – Hold Yuhh – YouTube, and POLITICAL PEAK & SNEAKBO – WAVE LIKE US – YouTube

- Skunk Anansi – Stoosh Album – by Brixton native Deborah Anne Dyer aka SKIN. She is the first Black British person to headline Glastonbury. My favourite from this album is ‘We Love Your Apathy’. A callout of our UK government and the public’s apathy to their political wrongdoings.

- It’s a love thing – Tippa Irie. This is my favourite song from him. As in, it’s playing at my wedding beautiful. Tippa Irie is a British reggae singer and DJ from Brixton, who came up in the 80s with sound system saxon studio international

- The Thirst- True. My favourite song from this band! The Thirst are an English indie rock band based in Brixton, London.

Restaurants

- El Rancho de Lalo: incredible Colombian food

- Light of Africa: Vegan/veg ethiopian food

- Wood and Water: previously known as 3 Little Birds, Caribbean food

- Etta’s seafood kitchen: Caribbean seafood restaurant, great taste and portions

- Healthy Eaters:Caribbean food takeaway

- Asafo: delicious Ghanaian food

- Morleys: it’s a must