Two weeks ago, eight people, including six Asian women massage parlour workers, were shot and killed in Atlanta, Georgia in the US. The deaths have resulted in an eruption of discussions about anti-Asian racism in the US – its historical roots and contemporary manifestations, how it relates to other forms of structural oppression including ‘whorephobia’ (the hatred of sex workers), and how we might tackle it.

For many of us in the UK, particularly those of us who have experienced racialised sexual fetishisation and violence, the targeting of Asian women massage workers struck a painful chord – especially in addition to the astronomical rise in violence – including physical attacks – against East and Southeast Asian people during COVID-19, exacerbated by frequent Sinophobic and racist media coverage.

Throughout the past year, we have seen sections of our community make frequent appeals to the state and the police to protect us, employing the language of ‘hate crime’. Hate crime is defined as criminal behaviour where the perpetrator is motivated by or demonstrates hostility based on a victim’s (perceived) race, sexuality, religion, disability or trans identity. Punishments for hate crime may be more severe because of this motivation. What this means is that if a crime can be shown to be driven by identity-based hate, the perpetrator may receive a harsher punishment than for the same crime committed without that basis. This could be a longer sentence, or a prison sentence instead of community service or a fine.

We understand the pain that motivates our community members’ calls for police protection and prosecutions. We know that organisers trying to address people’s historical distrust in the police have good intentions – that they are trying to address the fact that racism against East and Southeast Asian people has rarely been visibilised and taken seriously, using the tools that are available at their disposal.

However, turning to the state and police for help forces us to adopt its language and strategies. During a period when many of us are scared and suffering, we are encouraged to understand our experiences in the dangerous and limited frame of ‘hate crime’, and offered false promises that reporting to the police will somehow help us.

It is our belief that we must reject the ‘hate crime’ framing of our experiences of racism. Instead of petitioning the state for scraps, we can reimagine what safety and justice look like, collectively building mutual aid and support networks towards a liberated future for all.

Expanding police powers

We are concerned that while the expansion of policing may provide a sense of safety to some middle-class light-skinned East Asians, it will further harm the most marginalised in society, including within our own ‘communities’ – brown Southeast Asians, undocumented and low-paid workers, sex workers, and those experiencing other often-intersecting forms of precarity. We refer to ‘communities’ in quotation marks, because we cannot presume similar experiences between all East and Southeast Asian people—structural oppression puts certain groups in greater positions of vulnerability and marginalisation.

In the US, the Atlanta shootings have resulted in more police being deployed at massage parlours and in Chinatowns despite the fact that the police for a long time have frequently endangered migrant workers through violent raids on their workplaces. What is haunting is that the very structures of gendered and racialised state violence that daily push migrant workers and sex workers into conditions of danger, are being expanded in the name of protecting such workers. As highlighted by grassroots collective of Asian and migrant sex workers Red Canary Song, “[d]ue to sexist racialised perceptions of Asian women, especially those engaged in vulnerable, low-wage work, Asian massage workers are harmed by the criminalisation of sex work, regardless of whether they engage in it themselves.” Importantly, it is the criminalisation of sex work that creates precarity – not the work itself.

In the UK, ‘hate crime’ legislation is increasingly being connected to counter-extremism infrastructure under the term ‘hateful extremism’ – a system that has hugely expanded surveillance and criminalisation of Muslim communities over the past 20 years. A recent report has also shown that a disproportionate number of hate crime sentences are actually for verbal harassment of police officers by people in police custody, i.e. people who are already criminalised. In a recent case, a drunk homeless man was jailed for 16 weeks for calling officers ‘English bastards’ and ‘lesbians’ when they reprimanded him for swearing outside a police station.

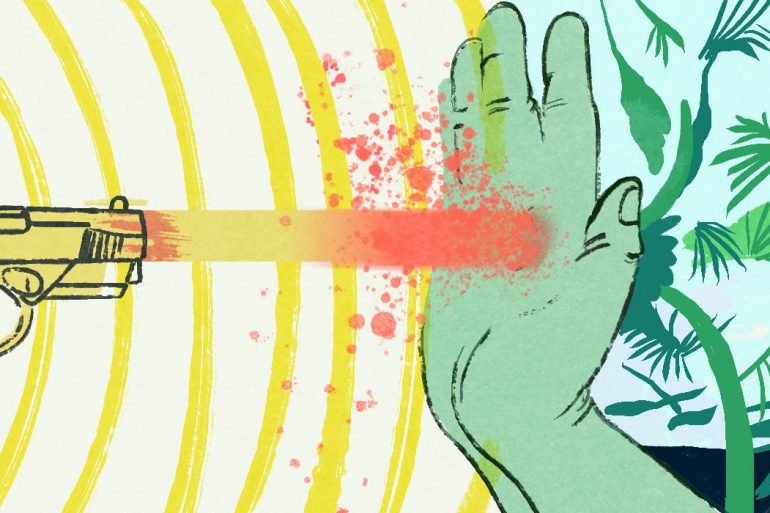

There is a long history of victims of racist attacks themselves being criminalised by police. In 1987, four waiters at the New Diamond Restaurant who defended themselves against a racist attack by white perpetrators were prosecuted and sentenced to time in prison. A similar incident occurred at the same restaurant between five waiters and eight attackers in 2000. More recently, in January 2021, a Chinese man and his friend were charged with public order offences after defending themselves from a racist attack in Liverpool. Community campaigners engaged in a concerted effort to oppose the CPS’s decision to continue with the prosecution. In the end, the court found the man not guilty, but the entire process led the victim to feel “worried… lonely and insecure”. Campaigners are tirelessly fighting to free Siyanda Mngaza, a young disabled Black woman who defended herself from a racist attack and was convicted by an all-white jury of grievous bodily harm with intent—she is currently serving a four-year sentence.

Finally, in the aftermath of the death of Sarah Everard, a group of Labour MPs are now trying to introduce the Nordic model – which criminalises clients and third parties in sex work – into the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill under the guise of “ending violence against women”. The move will only serve to push sex workers, especially migrant sex workers, into greater conditions of precarity. Meanwhile, campaigners continue to fight an uphill battle for migrant survivors – who cannot access mainstream refuges and benefits – to have access to public funds and for their data not to be shared with the police, so that they do not have to choose between staying with their abuser or being forced on the streets. That politicians are more concerned with criminalising sex work than actually pushing forward policies that will make a material improvement to the lives of migrant survivors demonstrates that they do not really care about fighting “violence against women”. Instead, what they want is to further extend the reach of the criminal justice system—with ultimately harmful effects for all.

Legitimising police

When people in our ‘communities’ use the language of ‘hate crime’ and engage with the ‘hate crime industry’, we are bolstering the police’s credibility and legitimacy. In reality, this works to reinforce the ‘model minority’ myth – in other words, the stereotype that East and Southeast Asians are more capable than other racialised groups of ‘pulling up our bootstraps’, assimilating, and ultimately succeeding within the structures of white supremacist society. Not only does this myth homogenise experiences between those racialised as East and Southeast Asian, disguising the inequalities that exist between various groups, it shores up the lie that is British ‘meritocracy’. The ‘model minority’ myth itself is used as a cudgel against Black and brown people who are comparatively portrayed as being unwilling or even incapable of replicating the same successes as certain East and Southeast Asian people, when in truth, the real obstacles are institutional racism and structural oppression.

We should be aware of how the state expands hate crime laws and initiatives precisely at points when the police are encountering crises of legitimacy. In a webinar organised in response to the Police Crackdown Bill, while discussing the police’s recent declaration that it would record misogyny as a hate crime, organiser Nim Ralph encouraged us to think about how calls for enhanced policing of hate crime are actually working to divide a movement that has coalesced around demands to abolish the police altogether. This must be understood as an attempt to co-opt and neutralise radical struggle against gendered violence by redirecting energies to bureaucratic and reformist politics.

Viewed in this light, we can see that our suffering is being used to disempower us and distract us from imagining otherwise and building communities of solidarity, resistance and care.

Decontextualising racism

As Remember and Resist, a campaign that was established to commemorate the deaths of 39 Vietnamese migrants who were found in a lorry in Essex in 2019 – victims of violent border regimes, histories of colonialism and imperialism, and economic oppression – we believe that the logical endpoint of calls for greater policing will only serve to individualise racist violence as an aberration, not unlike how individuals smugglers were blamed for the deaths of the Essex 39.

In the case of identity-based attacks, the nature of the criminal justice system is to individualise and decontextualise people’s actions in the name of ‘impartiality’, obscuring the conditions that created the violence in the first place. If a survivor of racialised and gendered sexual violence kills their perpetrator in self-defence, for example, they can be charged for manslaughter (see Cyntoia Brown, CeCe McDonald, etc.) – notwithstanding the fact that they are defending themselves against individual manifestations of structural violence.

If ‘hate crime’ is not only problematic but ineffective within its own logic, why does the state want us to name our experiences of racism in those terms? The reason in our view, is that labelling incidents as ‘hate crimes’ conveniently masks the state’s role in creating the conditions for that violence. In reality, racism isn’t simply ‘hate’: it is a form of structural oppression, a system of hierarchical relations created and sustained in order to justify the exploitation and expropriation of racialised people.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Towards alternatives

This is an opportunity to think deeply together to reimagine safety, and reimagine society in a way that is truly liberatory for all and not just those of us who are not generally subject to police and state violence. We are surely past begging the government and media for reformist scraps – they will suck all of our energy and reverse whatever small concessions they’ve given us as soon as they are able.

What is needed for our collective safety is the abolition of all oppressive systems, and a complete reimagining of our society. Abolition is as much a project about building as it is about tearing down–and it is about choosing to invest time in cultivation of relationships and support, rather than dependence on the state, which was never designed to save us anyway. We need to build connections across class and migration status within our ‘communities’, and to strengthen our solidarity with other racialised groups struggling against structural violence. But first of all, we must recognise that greater hate crime enforcement can’t – and won’t – save us.

Remember and Resist is a project seeking to expand abolitionist practice and thinking in East and Southeast Asian diasporas in the UK.

See more of Michelle’s work on instagram