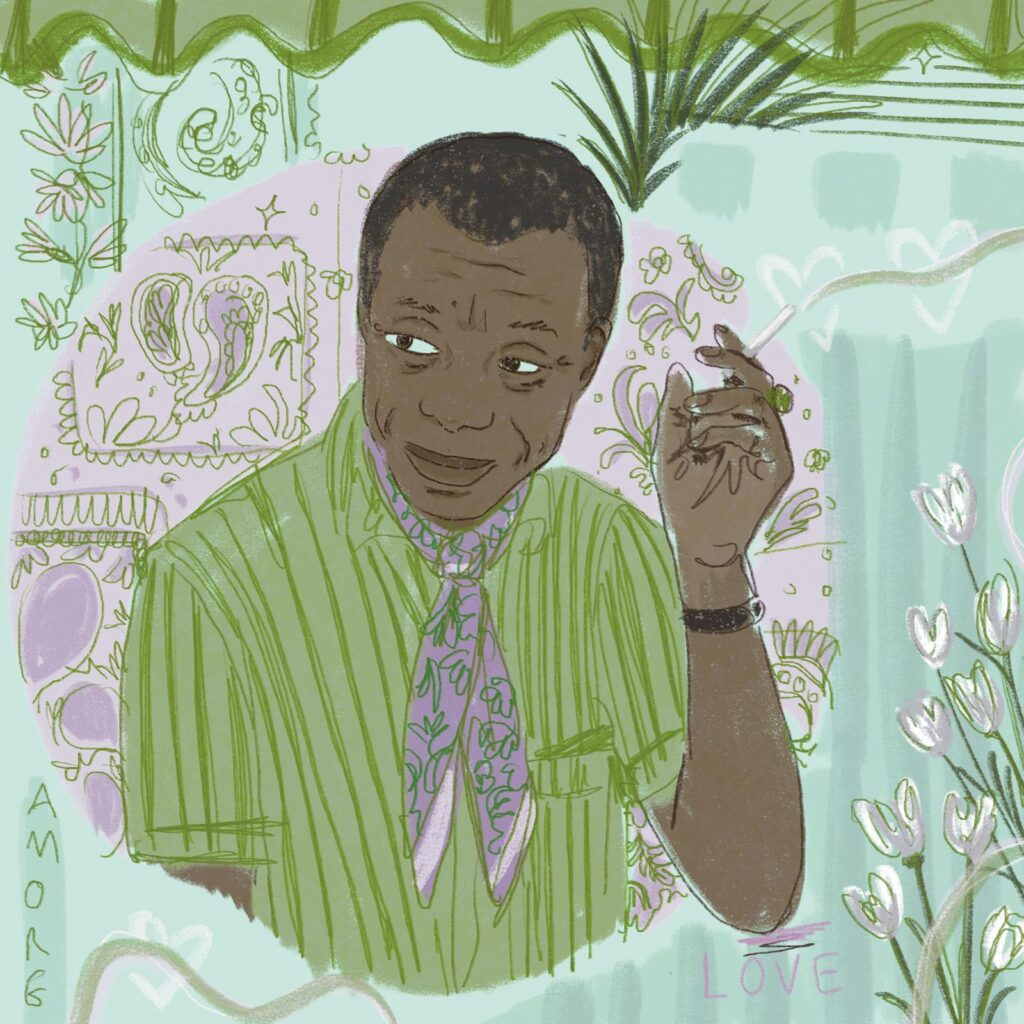

This month is James Baldwin month. I don’t know if there’s anything official, but let us all decide right now that it is so anyway. James Baldwin would have turned a century old on 2nd August, and his words are even more urgent now than they were when he wrote them.

The world we live in is rarely one where hope is obvious. If anything, the opposite is true: hopelessness is all around, and for good reasons. As someone who grew up in Lebanon, and whose family history is one of constant grief and forced displacement, I am no stranger to despair. It was discovering Baldwin that led me to conclude that hope is a matter of politics, a decision to take (and my podcast, ‘The Fire These Times‘, is named after his book ‘The Fire Next Time’). This might sound like a futile point to make, but bear with me. Baldwin had an answer to that. I won’t even use his entire body of work to demonstrate this. I will just stick to a short interview he did in 1970 in Paris.

But first, some context. 1970 is already after most of the events we now associate the Civil Rights movement with on Turtle Island (the USA). MLK JR was assassinated in 1968. Malcolm X in 1965. Medgar Evers in 1963. People all around Baldwin, friends of his, were being murdered, for years, as the 2016 documentary I Am Not Your Negro showed. Around the time of his interview, Angela Davis was put on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitive list and shortly thereafter arrested by the FBI’s white supremacist and Christian nationalist president J. Edgar Hoover.

Baldwin’s experience of living in this world was one which forced him to pay attention. “I don’t believe in white people. I don’t believe in Black people either, for that matter,” he says in that interview. “But I know the difference between being Black and white at this time. It means I cannot fool myself about some things that I could fool myself about if I were white.”

That one lived in a ‘free country’ in 1970 USA was one of the many things that Baldwin and other Black people could not fool themselves. They did not have the luxury of time to do so. Baldwin himself described multiple times being at the receiving end of police brutality. When not him, virtually everyone else he knew.

There was never a time – not a single day – in Baldwin’s entire existence when the fact that the USA was a white supremacist state wasn’t painfully self-evident. What white people did not understand, Baldwin realised at an early age, is that their own world was also being held together by a very small number of people, mostly those who were othered to maintain their relative privileges, who took seriously the practice of hope as a discipline.

This, of course, is Mariam Kaba’s framing. Hope as discipline, not merely a feeling that one has, like some possession that one can lose, but rather a verb, something to do. Baldwin put it even more simply. He called it love, and “love has never been a popular movement.” Why? Because “no-one’s ever wanted, really, to be free.”

The simplicity of his wording here may lead many to dismiss it as naive. Sure, who would really say they are against love? Baldwin would answer that most people wouldn’t say it that way, but they would act as if they believed it nonetheless, that they believed themselves to be incapable or undeserving of love. The moral failures we are witnessing in our world today come, in part at least, from cowardice. If you “walk down the street of any city” all you need to do is “look around you.” What you’ll find, of course, is despair and hopelessness.

Most of us stop there, but Baldwin didn’t.

“What you’ve got to remember is what you’re looking at is also you. Everyone you’re looking at is also you. You could be that person. You could be that monster, you could be that cop. And you have to decide, in yourself, not to be,” he says.This is why he concluded that “the world is held together by the love and the passion of a very few people.” Most of us who are housed see the unhoused as an aberration. Maybe we pity them, maybe we say that is sad, but we maintain a distance nonetheless.

That distance feels protective, like putting up a gate around your house or installing the latest security gadget in front of your flat. It won’t be me, at least. We may look at global warming and conclude the same. It’s over there, not here, at least not right now.

That’s the great lie that gives us a false sense of comfort. There is nothing in this world that prevents anyone from falling into a downward spiral. Anyone, anywhere can one day find themselves unhoused. The reasons preventing that fact – your privileges, your luck – are themselves heavily dependent on a multiplicity of other factors.

I was privileged in Lebanon, but not as much in Europe where I’ve been living in various stages of precarity since 2015. More so than some, less so than many, but my privileges are always deeply relative and relational. Like Baldwin, who had it much worse, I learned the hard way that the privileges I took for granted in Lebanon, the ones many take for granted in Europe, are themselves dependent on a number of other factors that I had little to no say about. What I do have, my chosen families and friends, was built. This was often done against and out of despair.

“The logic of despair isn’t for me,” Baldwin concludes. “There may not be, you know, as much humanity in the world as one would like to see, but there is some. There’s more than one would think. In any case, if you… if you break faith with what you know… that’s a betrayal of many, many, many, many people. I may know six people, but that’s enough.”

Baldwin didn’t even believe those who said they were in despair while keeping on writing, because someone who despairs “doesn’t write.” What’s the point of writing if you feel like it is hopeless anyway?

The very act of writing embeds in it hope, even if the words written do not. It is deeply contradictory, but it is true. Even the nastiest among us who write, those whose public politics is clearly built on fear and hate, still desire an audience. If everyone else dies, and the last person on Earth was a committed fascist, would he write? (Yes, I did assume that the fascist is a ‘he’)

These are the moral monsters that Baldwin identified. The people who refuse to see the Other as themselves, who are too cowardly to understand that they can be the people they are dehumanising.

The Israelis who made TikTok videos dancing to the agonising screams of Palestinians injured, dying or mourning their loved ones had to dehumanise themselves first. It cannot be done otherwise. You cannot be that disconnected from a human whose suffering you are celebrating without disconnecting yourself from humanity in the process. It requires a violent break from yourself, one which you may never recover from.

It is very revealing indeed that when not posting about the living hell that Israel has brought upon them, Palestinians on social media are posting videos of being in community. They’re cooking for others using humanitarian aid, they’re DIY-ing the rubble of destroyed homes and dreams into works of art, they’re getting their hair cut, they’re hanging out with loved ones and just being there for one another. If anyone needs examples of mutual aid, they’re there, every day. Palestinians are turning death into life, even as the world’s so-called democracies condemned them all to death. Why would they even bother if there was never any hope?

Palestine will be free, from the river to the sea, because of them. It may not always be so. This is why Netanyahu’s ethno-supremacist regime wants them all eradicated. This is why the IDF has made assassinating children a policy. They want to break Palestinians once and for all, at their core. They are actively mass-killing the innocent to break their parents. They want despair to become so thoroughly embedded in the Palestinian experience that Palestinians lose who they are as a cultural identity. We’ve seen this before. Armenians, Bosnians, Tutsi, Uighurs, Rohingya, Jews. We’ve been here before.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

“I’m aware, you know, that I and the people I love may perish in the morning,” Baldwin said in that interview. As we saw, he wasn’t being metaphorical. His loved ones were already murdered, others will be in the future. Death was all around Baldwin, all the time, “but there’s light on our faces now. If you live under the shadow of death, it gives you a certain freedom.”

Happy birthday Jimmy.

What can you do?

- Watch I Am Not Your Negro (2016) by Raoul Peck who uploaded it for free on the Internet Archive

- Watch the 1971 conversation between James Baldwin and a young Nikki Giovanni on YouTube

- Read his 1955 collection of essay “Notes of a Native Son”

- Continue calling for an immediate ceasefire to stop Israel’s genocide in Gaza and for your governments to support ICC and ICJ proceedings. Support BDS until Apartheid is defeated.

- Read more of Elia’s articles HERE

- Keep up to date with shado’s coverage of Palestine