It is a Saturday afternoon in late April, and I am sitting in a greenhouse near Tottenham Hale in Haringey, North London. At least 20 people have gathered for the London Renters Union (LRU) local branch meeting in Haringey. The greenhouse, which is part of the Community Centre, serves as a meeting room for all kinds of groups in Haringey and Tottenham, from feminist gardening to Palestine liberation.

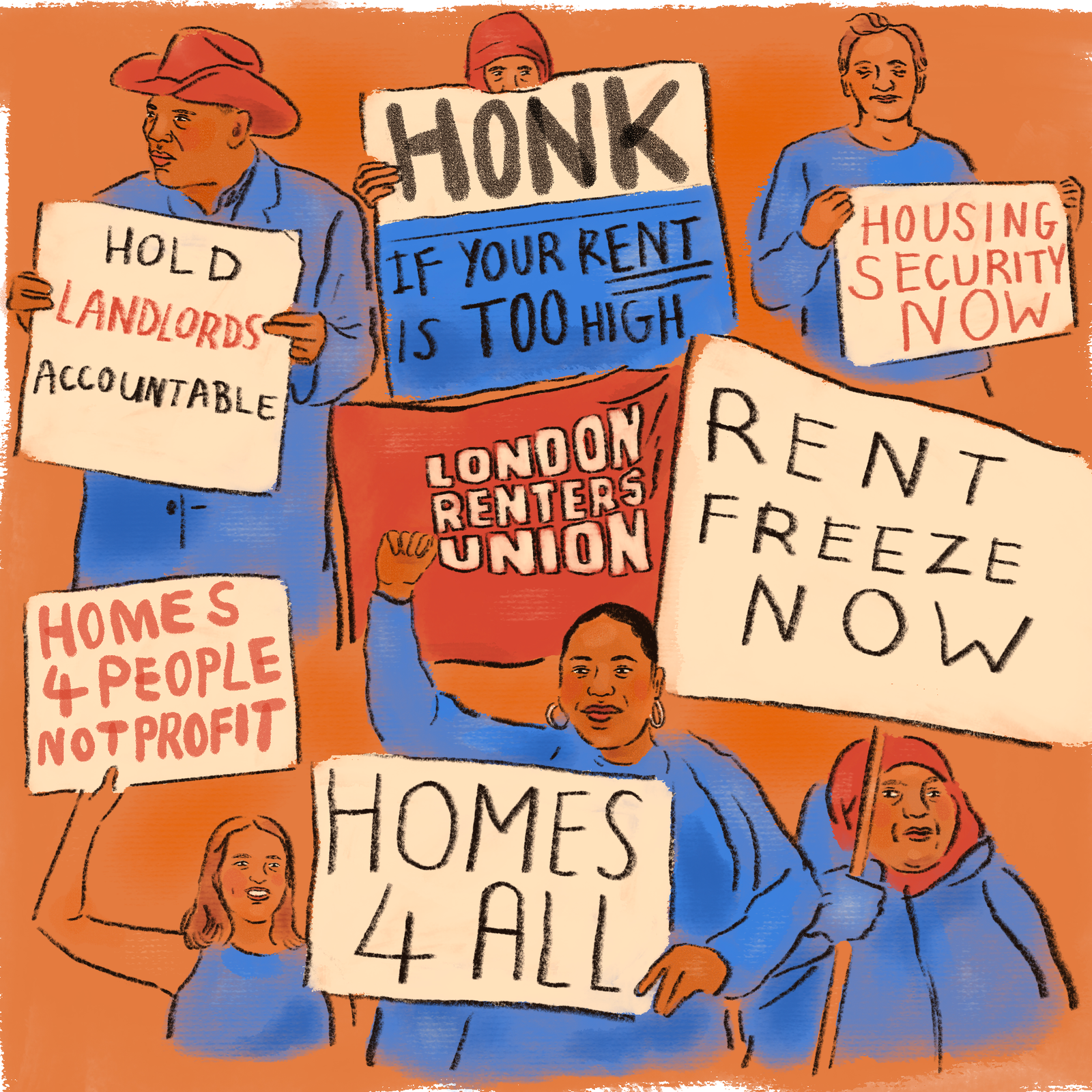

The sun shines through the glass ceiling, warming my face as I listen to Nadz, activist and staff organiser with the LRU, who is leading the meeting. Founded in 2018 by a coalition of housing groups and social justice groups, the LRU aims to transform the housing system so that everyone has access to an affordable, secure, and decent home.

“Housing issues can make us feel super isolated and super alone. And you know what? It is by design, they want to isolate us, they don’t want us to know about the few rights we have. We are much stronger when we show up for each other. That is why unions are so important. We support each other and we take back the power”, Nadz says.

A rigged system

Peer support is a crucial part of the union and of every meeting. Members share their housing problems and support each other as much as they can.

One member shares that she was served a no-fault eviction notice by her landlord a few days ago. Section 21 of the Housing Act allows landlords to evict their tenants for no reason and with just two months’ notice. Given just two months to leave her flat, she now faces the daunting task of finding affordable housing in one of the most expensive cities in the world. Another member has been living with black mould in his flat for months and although his landlord is aware of it, he has not done anything about it.

As horrible as they are, their stories are not isolated cases, but rather symptoms of a rigged and deeply unjust housing system. They echo the experiences of countless renters in London and all over the UK who find themselves vulnerable to the whims of landlords. Over the last two decades the housing crisis has spiralled out of control. Without radical change, it will only get worse.

Homelessness on the rise

The consequences are already severe. Tenants have little security and even less power. With ever-rising rents and rampant gentrification, more people are priced out of their neighbourhoods, forcing them to leave their communities and their security systems.

At the same time, many people are forced to live in hazardous and inhumane conditions. According to a report by the BBC, almost 20% of privately rented homes are thought to be in a hazardous condition, while others cannot afford rent at all and end up on the streets.

Latest government figures show that roughly 300,000 people in the UK are homeless and 140,000 children live in temporary accommodation. What is more, reports show that three and a half million tenants are worried about becoming homeless as a direct result of rising housing and living costs.

Racial inequality in housing

We are all affected by the housing crisis, but not equally. The housing crisis perpetuates racial inequalities and puts undocumented migrants, those without a permanent residence and racialised people at a higher risk.

According to Shelter, Black and Asian people are far more likely to be denied the right to a safe and secure home. When looking for a home, they often face racism and discrimination from landlords or institutions. As a consequence Black and Brown people are more likely to then end up in unsafe and unsuitable housing or worse, on the streets. These injustices are not created by a few racist landlords, but they are deeply enshrined in the housing system.

But it does not have to be that way. The housing crisis is not an accident, nor is it an inevitability. It is a product of political decisions, consciously manufactured by generations of landlords, governments, and policy makers to preserve their power and protect their wealth.

Rip-off rents are a political choice. And so is homelessness and deadly mould.

Landlordism, not scarcity, causes the housing crisis

A few weeks after the meeting in Tottenham Hale, I call Nick Bano, an author, activist and barrister who specialises in representing unhoused people, residential occupiers and migrant households. In his recently published book, he argues that the root cause of the extreme housing crisis that we are facing is the system of landlordism that is so deeply embedded in Britain’s legal and economic structure.

He explains: “We live in a context in which rents are totally deregulated. Landlords can ask whatever price that the tenant is able to pay. Rents rise even where conditions are in very sharp decline: they do not find their limits through competition, but by coming up against the hard limits of tenants’ means.” We live in a world of ever-rising rents, which, in turn, means ever-rising house prices.

This is because house prices are ultimately defined by rental yields. “The financial value of any house is ultimately determined by the price that a landlord would be willing to pay: and that, in turn, depends on its potential to generate rent,” Nick adds.

His point counters one of the most dominant narratives about our current housing crisis, which is the idea that the housing crisis is only caused by a lack of housing and that to solve the housing crisis we simply need to build more housing.

Figures from the Office for National Statistics, however, show that this is not true. Scarcity of buildings is not the problem. Quite the contrary: the ratio of homes to households in Britain has increased in the last decades. The houses are still there and there has not been a drastic change in the population to make them inadequate. In fact, most housing in England and Wales is under-occupied (70% in 2021).

Decent housing for everyone

It is against this backdrop that the LRU is organising. I meet up with Nadz again in early June, in a café near their home in Haringey. “We know that there’s thousands of empty units across London and across the country,” Nadz tells me. “The problem isn’t always that there isn’t enough houses there. That’s a myth that we’ve been told.”

They continue: “We do not need another tower of luxury flats, what we need and what we want is public housing for all.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

This should really include everyone, not only British citizens, but also people without a British passport, without indefinite leave to remain and with no recourse to provide funds. Every person, no matter who they are, should be able to have a home. It is bizarre that this is something we even have to fight for, something that is considered radical, when really it is the bare minimum.

“I think the public and the general population should be able to own and have control over the homes that they live in,” Nadz adds. “I don’t think that landlords should be part of that and I don’t think that they make any of our lives better.”

And why would they make our lives better? They make money off one of the most basic human needs, which is to have a roof over your head, to have a house. All landlords, regardless of how nice they are, benefit from this system. A system that commodifies housing.

Abolishing landlordism

To fight the housing crisis, then means to withdraw power from landlords as much as possible and give it back to renters, until eventually landlords have no more power over our lives.

Just 50 years ago, that was almost the case – landlordism in this country was nearly abolished. Only 6% of all homes were privately rented homes. Then Thatcher came and abolished rent control and introduced section 21 and the right-to-buy among other things. That was in 1988.

“Of course we cannot transform the housing system in a day,” Nadz says, “but introducing rent control would be a first step.” Rent control is one of LRU’s main demands. Just a few weeks ago they kicked off their campaign for rent control with a direct action in front of Graingers, one of the biggest developers of the country.

“Rent controls are so important because they give people more stability and more security. And they take a bit of power away from landlords because it halts them from raising the rent as arbitrarily,” they explain. And all renters would benefit: private renters, whose rents would be capped, as well as tenants who live in council or social housing – because usually their rent is valued against market rent.

Rent controls would immediately improve the living conditions of the many. Especially those who are currently struggling to most, would feel the effect.

“But capping rent alone is not enough. Even the current level of rent is too high for many people. So we know that rent controls would need to be backdated and over time lowered,” says Nadz. Next to rent controls the LRU also campaigns for the abolition of section 21, against discrimination and bordering practices in housing and for fire safety and better health conditions for all tenants.

No-fault evictions have to go

There is still a long way to go. In April 2019 the government promised to end “no fault” evictions. More than five years later, the Renters Reform Bill which should have abolished section 21 still did not pass. And so landlords continue to evict their tenants for no reason with just two months’ notice.

In the first three months of this year alone, county court bailiffs evicted 2,682 households in England and Wales as a result of landlords issuing section 21 “no fault” eviction notices. In all of it is always the most vulnerable people who are hit the most by the horrors of the housing system, the poorest, racialised people, migrants, disabled people.

“The grandness of it all can be overwhelming sometimes,” Nadz admits. “But organising with my neighbours, friends and comrades gives me hope.” They smile: “We also see that those things can work, we do win. Our comrades in Scotland set up rent controls and so did our comrades in Barcelona. We are a lot of people and we are a strong union. We are getting really organised and I don’t think politicians can ignore it forever.”

As I walk home from my meeting with Nadz I feel a renewed sense of hope. We are many and collectively we can make change happen. This is not just about housing; it’s about reclaiming our right to live with dignity and security. Together we can strip away power from landlords shaping a future where housing is affordable, secure, and accessible for all.

What can you do?

Books and articles to read:

- Nick Bano, Against Landlords

- Leslie Kern, Gentrification is Inevitable and Other Lies

- Ida Danewid,The Fire This Time: Grenfell, Racial Capitalism and the Urbanisation of Empire

- What is Gentrification?

- To All The Blocks I’ve Loved Before

Podcasts

- Surviving Society, How we let Grenfell happen

- Movement Memos: Reclaiming Life and Housing in an Era of Collapse

- The Verso Podcast: A Land without landlords

- Surviving Society: A brief history of social and council housing in post-war Britain

Groups