Noora was nine years old when she was meant to perform Dabke, a traditional Arab folk dance, for the first time. The setting was Jerusalem’s Al Hakawati Theatre. She, and all the other children in her dance troupe, El-Funoun, were incredibly nervous and excited to be on the stage. As she poked her head around the backstage area into the open theatre, she could see her mother, father and sister sat, awaiting with equal anticipation and joy.

“My trainer at the time, Khlaed, who was as excited as we were, was giving us last minute feedback and directions,” 43-year-old Noora tells me via email. “It was then when I heard the audience gathering outside the theatre cheering and calling for the liberation of Palestine and the end of occupation, something that happened regularly at any Palestinian gathering or event.”

“Shortly after came the chaos and screams. Khaled picked me up by the waist like a sack of potatoes and he ran with me and the other children towards a closed room where he gathered us together to keep us safe,” she recounts. “I peeked out the small window looking towards the outdoor area of the theatre where Israeli occupation soldiers, with their guns and sticks, started attacking the audience. I saw my sister being dragged by the arm with my mother and father. One of the soldiers spotted me looking and immediately threw tear gas into the window and into the room full of us children. Everything became blurry after that.”

The personal is political

Unsurprisingly, Noora did not get to perform that day. Yet the trauma from that experience has shaped her relationship with dance ever since. Noora has been with El-Funoun for 36 years, and she’s now the troupe’s Head of Production, following years of performing, choreographing and directing. “It’s difficult to define my role in El-Funoun. It is my main project in life, a humbling experience and a continuous eye opener. I am a part of it and it is part of me. My outlook on life, philosophy, ethos and art is intertwined and shaped from the practice of growing with El-Funoun,” she tells me.

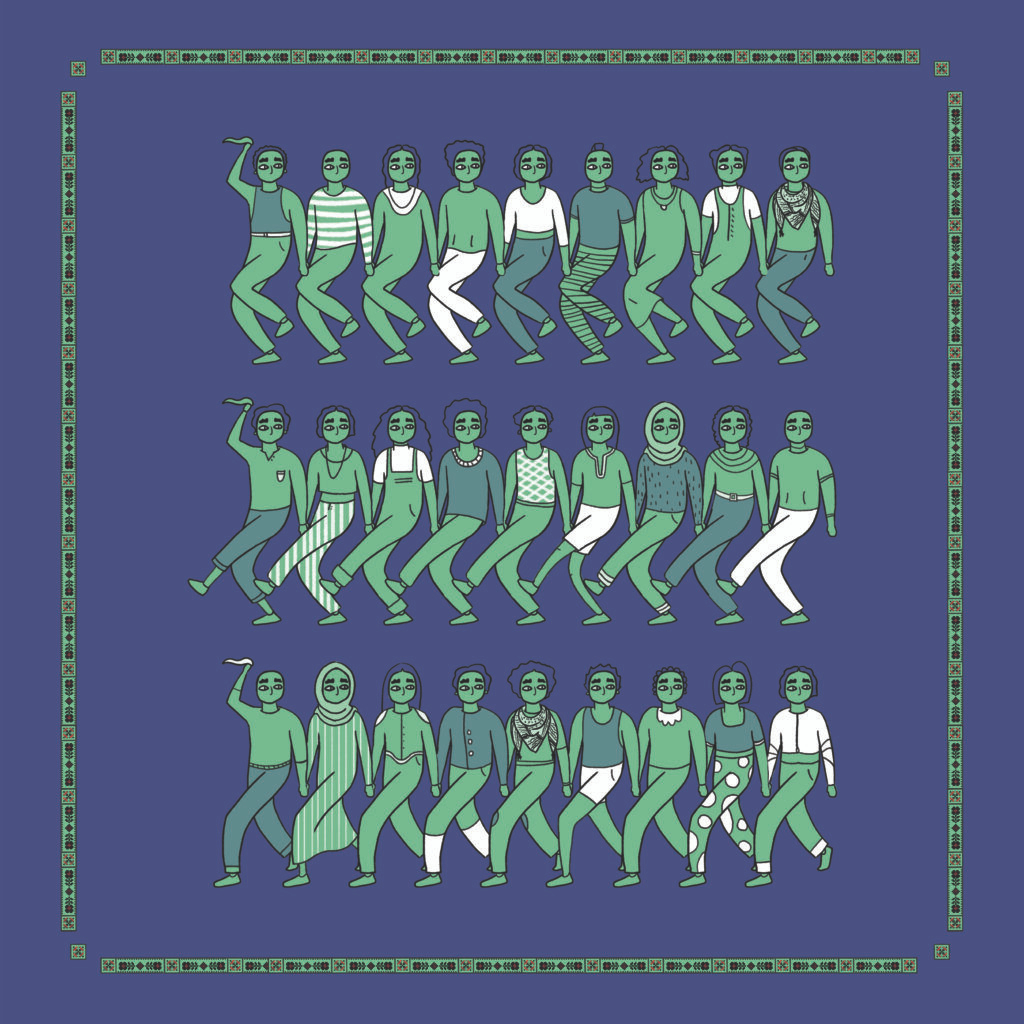

El-Funoun, established in 1979, is a non-profit volunteer based dance troupe that continues on today, using dance as a tool for the expression and celebration of a rich Palestinian culture and heritage.

Indeed, the organisation’s utilisation of dance as a means to address the fight for Palestinian liberation speaks to a long history of creative arts as a form of political power and resistance. From the role of ballet in protesting the US government’s immigration policies in 1923, to those performing the Cupid Shuffle in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, dance has the unique ability to convey powerful political messages through actions rather than words.

Stamping for freedom

A paralanguage of sorts, artists have always found ways to use their bodies to connect them to their surroundings and challenge the injustices of their time. Nowhere is this more evident than with the revival of Dabke, a traditional Arab folk dance which loosely translates as ‘stomping on the ground’.

Abu Hani is a revered Palestinian scholar and folklorist who, whilst performing Dabke at the same time, said this when describing the essence of the dance:

“They have stolen our land [stomp], forced us out of our homes [stomp], but our culture is something they cannot steal. When we stamp our feet, we are saying that no matter how far we have been scattered, Palestine will always remain under our stamping feet.”

While its origins are contested and mean different things to communities throughout the Middle East, Palestinian iterations of Dabke are increasingly being performed by communities all over the world to protest the humanitarian crisis facing Palestinian people.

Whilst Noora was born and raised in Palestine, and remains based in the central West Bank city of Ramallah, many young Palestinians in the diaspora have not had access to the country of their ancestors. Indeed, Israel’s oppressive legislation, contrary to international law, has prevented over 5.2 million Palestinian refugees from returning to their homeland, with further legislation often preventing diaspora from visiting, never mind resettling, there. This makes their relationship with the land an abstract, ‘imagined’ one. So Dabke, in its performance, provides an opportunity for Palestinians to reaffirm their identity: an opportunity to celebrate their culture and also engage with the political challenges in their native land. If they cannot walk on what is theirs, they will dance for it all over the world. Each stamp is an expression of statehood, of love, longing, anger, and resistance.

Dabke around the world

Hawiyya Dance Company, a London-based all-women Dabke collective, is one organisation doing exactly this. One of Hawiyya’s founding members, Shahd shared how Dabke plays an important role in raising awareness for the Palestinian cause.

“After 1948 and the creation of Israel, which displaced two-thirds of Palestinian people, Dabke started taking on a political meaning. The whole Palestinian heritage was under threat of extinction, so Dabke became an expression of resistance to show that our history is rooted in this land, that we belong to this land, that we love this land, and that we will never forget our rights to return to this land,” Shahd explains.

Since its beginnings in 2017, Hawiyya has worked closely with refugees and Arab communities through a range of workshops and performances. “Dabke helps encompass the shared struggle that so many of us face,” she says. “So, for us, dancing is an expression of togetherness and a way to express happiness and joy.”

Edinburgh-based Samar, who dances Dabke with his local community, also shared the importance of Dabke as an expression of loss. He started learning Dabke in weddings as a child, but has revived his love and dedication to the dance form in the past few years.

“Dabke helps us to be resilient and to release the sadness in the heart of when remembering loved ones who passed away, and the loss of livelihoods as a result of the greediness of occupation,” Samar says. “It connects us to our struggle, to our martyrs in Gaza, to the refugee camps in Rafah who suffer the most.”

Dabke today

The recent escalation in violence and persecution faced by Palestinian people in the genocide which has been raging since October 2023 has come hand-in-hand with the growth of Dabke’s online presence. From children dancing in the streets of Gaza posting TikToks and educating their internet audience about their culture, to diaspora in exile and in refugee camps, to activists and allies worldwide learning Dabke at demonstrations in solidarity with the movement, it is clear that interest in the dance form is growing. Political consciousness and community are being enhanced through this form of cultural and artistic production.

“The symbol of Dabke is more important today than ever before – look at how it has re-emerged on social media!” says Noora. Dabke, Kufeyeh, embroidered dresses, olive trees, pomegranate trees, songs of the Intifada, and the watermelon are all symbols re-emerging today in the fight against oppression.” The very act of performing Dabke is a political statement, and an incredibly powerful one.

Dabke is also helping to reframe the current worldview of Palestine. Reductive headlines of a war-torn country give us few glimpses into the rich cultural heritage that has existed throughout hundreds of years of Palestinian history.

As Shahd says, “Palestine only hits the news when it is under attack or launching an attack. We don’t see much of who the Palestinians are. We are often instead reduced to a threat or helpless victims under attack. So Dabke brings another side to Palestine; a side that is often underrepresented and missing in this narrative of violence. It reminds us of our cultural identity.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Dabke will continue to create and uphold a community in a way that only art can. For Noora, Shahd and Samar, their love of country and of dance go hand in hand. Every stamp of their feet is an act of cultural retention. In the words of Noora, “I am a proud Palestinian rooted in this land and I am here to stay. I exist and the world needs to recognise that.”

What can you do?

Actions:

- Actionable ways to support the end to the genocide of the Palestinian people – a comprehensive set of actions to take

- Palestine Solidarity Campaign – join as a supporter and follow for information on marches and further actions

- Medical Aid for Palestine – donate

- Call for solidarity – Mosaic Rooms – call for cultural organisations, artists and writers

- Take action today, War on Want – links for taking many actions

- Write to your MP

Read:

- Against the Loveless World by Susan Abulhawa

- The Woman from Tantoura by Radwa Ashour

- The Secret Life of Saeed the Pessoptimist by Emile Habiby

- Gate of the Sun by Elias Khoury

- A Little Piece of Ground by Elizabeth Laird

- The Question of Palestine by Edward W. Said

- The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine by Ilan Pappe

Watch:

- A collection of films from the Palestinian Film Foundation