Last month I had the pleasure of watching two plays at PalArt Festival 2025: Application 39 and Return to Palestine. Afterwards, I also had the opportunity to speak to Ahmed Masoud, founder of PalArt Collective and director of Application 39, as well as to Gráinnemir Abualrob and Osama Al Azza, two performers from the famed Freedom Theatre ensemble who told me about Return to Palestine.

I went into these plays without knowing what I was about to watch, nor how I would link the two together in a packaged piece. Yet out of my hurriedly scribbled notes and swirling thoughts emerged a set of more-or-less coherent reflections, underpinned by a celebration of resistance arts.

Resistance arts is a mode of expression employed by the great revolutionaries of the Palestinian struggle, past and present. It is multifunctional: firstly, it allows us to slow down to mourn our martyrs, to register their names and stories as more than numbers subsumed by an unrelenting news cycle. But beyond this, it allows us to articulate what often goes unsaid: revolutionary hope, our dreams of liberation that guide our movement, our strategy, our action.

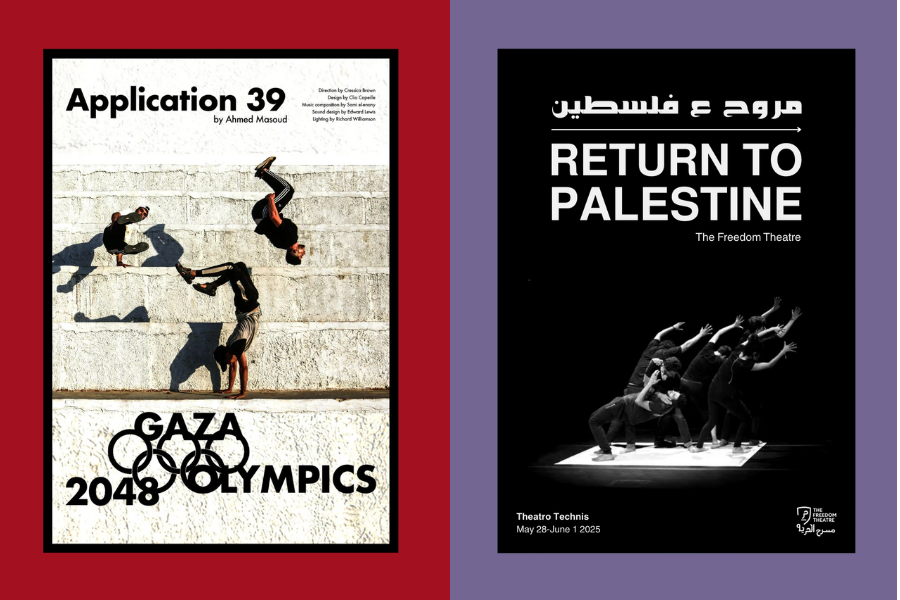

Application 39

Application 39 was originally written in 2019 for the Palestine +100 anthology series. This eclectic selection of dystopian science fiction brings together 12 Palestinian authors to imagine what Palestine could look like in 2048, 100 years after the Nakba. The resulting stories are striking; one of my personal favourites, The Key by Anwar Hamed, conjures up a scene in which Israeli settlers are haunted by the sounds of a phantom returnee’s key rattling their front door. In Application 39, Ahmed Masoud imagines a dystopian future in which the 2048 Olympics are to be hosted in a ravaged Gaza still reeling from a genocide carried out years prior, back in 2025.

This year, our 2025, as Ahmed started to adapt his piece for the stage, he was disturbed by his own prescience. Gaza is indeed ravaged by Zionist genocide, fragmented and separated by military corridors from which IOF forces massacre Palestinians as they wait for humanitarian aid, where remotely-operated drones and quadcopters shoot to kill. This is not science fiction.

After years of experiencing Gaza’s siege and witnessing several iterative bombing campaigns against the enclave, Ahmed knew genocide was a possibility. It would be the natural next step for Zionist settler-colonial expansionism; an acute concentration of annihilatory violence unleashed in order to “finish the job” and finally – impossibly – ethnically cleanse Palestine of all Palestinians.

Yet, as he sat down to reread his piece, Ahmed was still rocked by the realisation that “the now is the future”, as he put it, or rather, that the future he had anxiously anticipated was now a present reality. It’s one thing to imagine this scale of mass death and destruction, to try to brace oneself for it, to write about it abstractly; it’s another to face it as a reality, no longer as something yet to come but as an inescapable waking nightmare.

As time collapses in on itself and the fiction materialises in visceral violence, how do we hold on to our Experiments in Imagining Otherwise? How do we make sense of our future through an unsettled present? Or, vice versa, how can an articulation of a distant future allow us to comprehend our present, to begin to honour and grieve our martyrs before we can provide them proper burial? And how can all this be rendered legible in a theatrical production, on a stage in London and within the set run-time?

Ahmed deftly grapples with these questions in both his original piece as well as in the stage adaptation. The decision to interpret the present from the future provides Ahmed with the space to assess the political conditions that have led us to this moment and to subtly offer his analysis and critique. For example, in the play’s world, we are in 2048, reckoning with a post-genocide world order in which Gaza has been cut up into bantustanised mini-states in competition with one another. I read this as a provocation on Palestinian/Arab disunity and fragmentation, the obstacle in the way of any viable political project against Western imperialism.

Ironic humour is another way to unpack the spatiotemporal dissonances we are collectively facing. Throughout his acerbic adaptation of Application 39, Ahmed’s subtle nods to the Arab regimes’ normalisation of ties with the Zionist entity, as well as to current Palestinian Authority officials, are met with knowing chuckles. He also pokes fun at the “ceasefire” in which Zionist violence continued unabated: in the play, Gaza has been stuck in Phase 1 of the ceasefire for 22 years, an absurdity that makes the audience laugh precisely because it is not far from the realm of possibilities.

The play’s present is bereft with the weight of the genocide, both physically and metaphysically. The play asks, for example: how should the rubble that remains strewn around be memorialised? Should it be used to rebuild? And, if so, to rebuild what? Or should it all be swept up and discarded, forgotten – an ultimately impossible task?

Here, past violence is a burden that does not seem to ease with time, in spite of the political arrangements, peace treaties and empty gestures that seek to launder persistent imperial and settler-colonial control. The play suggests that this is because justice and liberation have yet to be achieved.

Indeed, for Ahmed, the present genocide is “the elephant in the room,” one he can only address by putting distance between it and himself/the audience, setting it in the past as something to reflect on.

Ahmed punctuates the linear chronology of the plot with episodic “flashbacks” to our real, current timeline: with this choice, he expressly intends to “let the present live and breathe on stage.” Some of these harrowing scenes we are already familiar with; for example, Ahmed references Dr. Hussam Abu Safiya’s continued imprisonment and torture at the hands of the Zionist entity. Others are based on stories from Ahmed’s own family and friends.

Perhaps the intimate pain Ahmed experiences and the overwhelming devastation the audience witnesses can only be interpreted and articulated in posteriority. Simultaneously, Ahmed’s inclusion of specific people’s names and specific junction names in Gaza allows him to record the present for posterity’s sake, to honour this presence in the face of annihilatory absence.

All of this is underscored by the martyrdom of Ahmed’s sister-in-law Ibtisam and his nephew Mahmoud only a few days before the play premiered, a year and a half after the martyrdom of his brother Khalid. My viewing of the play and conversation with Ahmed are both suffused with this acute loss, a personal tragedy representative of a collective one. This loss is naturally attended by the need and simultaneous inability to mourn that which is still unfolding.

The play thus becomes, for both its creator and audience, a way to begin reckoning with this mass devastation and destruction, even if it doesn’t go all the way. From there, we are able to take stock of the political options that are available to us so that we may envision and set in motion the future we seek rather than the one presented to us in the play. What will Gaza in 2048 actually look like? What must we do now so that Palestine is free by then? These are crucial exercises in (re)imagining liberatory futures that we must engage in – creatively and organisationally – so that we do not submit to despair or defeatism and instead move forward with intention, vision and hope.

Return to Palestine

And for all the Palestinians in exile, whether scattered around the world or trapped in besieged refugee camps, what could be more invigorating than keeping the inevitable return to a liberated Palestine as our North Star? Indeed, the “right of return” is one of the Palestinian Thawabit, a set of inalienable rights and core political principles that direct the Palestinian struggle. This allows the struggle to determinedly trudge along towards its goals, despite defeats, death and destruction along the way.

The spatiotemporality of return is intrinsically non-linear and multiple, a cyclicality long represented in Palestinian resistance literature and film. Going back in time is impossible, although there is much to learn from our past, the repository of our mistakes and wins, but most importantly, of accumulated dreams. But return in a material sense is possible. We saw this enacted by the people of Gaza during the short-lived ceasefire, when hundreds of thousands of displaced Palestinians marched back north to their homes, in a display of ferocious steadfastness. These scenes were heartening and emboldening; not only must we hold on to them dearly, we must work towards reenacting them on a mass scale.

But what does this look like? How do we imagine what has been rendered unimaginable by decades of imperial violence? How can we imagine a free, contiguous Palestine when Palestine has been so deformed by settler-colonial occupation? And what can resistance arts do to help us imagine?

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Right after watching Application 39, I sit down again for Return to Palestine, an ingeniously choreographed piece of “playback theatre” originally conceived during the Freedom Theatre’s annual Freedom Ride (also known as the Freedom Bus).

As the Freedom Theatre troupe made their way around villages, towns and refugee camps in occupied Palestine, they gathered stories of displacement and hardship (as well as of steadfastness and resistance) from these communities and then spent three years shaping and adapting them into what was to become Return to Palestine.

The stage is stark and empty, with no props and no costumes. This decision is partially intended to reflect the restrictions placed on the Freedom Theatre itself, which was founded in 2006 within Jenin Refugee Camp, the site of decades of extreme Zionist destruction, siege and displacement. This violence came to a head earlier in 2025, when the IOF stormed and occupied Jenin (as well as other key locales in the occupied West Bank), launching a deadly military offensive that has destroyed Palestinian infrastructure and displaced tens of thousands of Palestinians to date. This latest invasion saw the Freedom Theatre occupied by IOF forces; it is still inaccessible. Even as I write this article, we receive news of more demolished homes in Jenin.

A striking feature of Return to Palestine is its physicality. Throughout, the seven actors are limited to a small rectangular strip of the stage, evocative of Palestine’s “compressed reality.” But this small stage allows the actors to command each scene and turn it into a “playful space”. Here, the imagination roams free and the actors, nudging the audience along with them, “free [themselves] from [themselves]”. The actors’ seven bodies turn into one well-oiled machine, in intimate communion with one another as they recreate stories from the Freedom Ride using only their limbs.

I ask Gráinnemir Abualrob and Osama Al Azza about this tactility, and they explain that they view it as an expression of steadfastness, in that they “can keep going when sticking together and holding each other.” Having grown up together, this coordination and trust comes as second nature. In other words, it is an act of resistance against spatial restrictions and attendant attitudes of despair (or “psychological occupation” as Gráinnemir and Osama termed it) widespread across the West Bank. It is the reclamation of a fraught existence, the embodiment of a refugee camp’s “own special chaos” and an assertion of Palestinian oneness and unity in the face of hegemonic forces that seek to divide and conquer, both geographically and psychosocially.

This objective is reflected in the play’s very title and its plotline. The main character is the child of exiled Palestinian refugees. He returns to Palestine for the first time, and once there, discovers a community that embraces him but also comes face-to-face with the pain and violence that is borne out of occupation.

I ask Gráinnemir and Osama how they interpret return, especially considering how these dynamics were present in their own upbringings. Gráinnemir is from Jenin, where the Freedom Theatre provided them with valuable tools to navigate queerness in a socially-conservative society and resist Zionist occupation and violence through liberatory forms of cultural expression and community engagement. Osama grew up in ‘Azza Refugee Camp near Bethlehem, right next to the Apartheid Wall, later moving to Jenin to join the Freedom Theatre. They both now live in exile themselves, in Dublin and London respectively. Indeed, Osama emphasises to me the importance of using the term “exile” rather than “diaspora” in reference to all Palestinians unable to return to a free Palestine, explaining that “we should call it as we see it, not how it’s imposed on us.”

For Gráinnemir and Osama, the right of return now applies to them as well and not only to the refugees of 1948 or 1967. They tell me that, in order to secure this right and act upon it, we must organise our communities with long-term vision; yes, we must stop the genocide by all means necessary, but we must also work towards Palestine’s liberation.

Right after Return to Palestine, the audience was invited to stay and attend an online talk with Zakaria Zubeidi and Mustafa Sheta, two key figures in the Freedom Theatre’s history. We were told that both Zakaria and Mustafa had just recently been released from Zionist occupation prisons as part of the ceasefire deal which saw hundreds of Palestinian prisoners return to their families and communities.

It was only halfway through the talk that I realised that Zakaria Zubeidi, besides being one of the Theatre’s founders, was also one of the famed Palestinian heroes from the Gilboa Prison Break, in which he and five other Palestinian prisoners used a spoon to dig a tunnel and escape Zionist imprisonment. The man-hunt that pursued was keenly followed by all Palestinians, who saw in the prisoners’ struggle an undying fervour for achieving freedom and liberation. This fervour is illuminating for the rest of the movement, as we falter and risk giving in to despair.

Both Zakaria and Mustafa expressed how, during their time in prison, all they thought about was the Freedom Theatre: how to portray the prisoners’ struggle on stage, how to call for Palestinian unity at home (and beyond) through theatre, how to galvanise Palestinian polity into strategic action.

In a particularly poignant moment, they referenced Walid Daqqa, the famed Palestinian revolutionary, who was martyred in prison after being denied medical treatment for his terminal illness and whose body remains in captivity, an example of Zionist necro-carcerality in which a prisoner must complete their sentence even in death. Amongst his many influential political writings from prison, Daqqa had considered how “the imaginative mind creates another reality that bypasses the prison walls”. He notes however: “this should not imply that my writing is a dissociation from my reality inside the prison. On the contrary, as much as it is a creation of textual reality, writing is a methodological tool to deconstruct and make sense of my reality as a prisoner.”

Zakaria put it similarly: “if you cannot free your body, you must free your mind.” For him, without access to the Freedom Theatre, he realised he had to “create a theatre within [himself]”, a decision that the prison guards confused for psychosis, sending Zubeidi to the medic’s office.

Yet, in light of all the odds stacked against us, believing in the ascendance of our struggle and the inevitability of Palestine’s liberation does require a form of psychosis, one we should embrace wholeheartedly. When genocide persists and repression in the imperial core intensifies, it is revolutionary optimism that delivers us from depression and dejection.

Our struggle should not be aestheticised or reduced to a consumable artistic project. Instead, we should identify the role that art (like theatre) can play in stitching back together our isolated and fragmented communities and unifying them around a shared vision, a shared strategy, a shared imagination. Art helps us articulate our hopes and then enact them, even if only for a little while, on a stage where we are the masters of our own destinies.

What can you do?

Read:

- Palestine +100: Stories from a Century after the Nakba, edited by Basma Ghalayini

- A Place Without a Door and Uncle Give me a Cigarette, two essays by Walid Daqqa

- On Pressurising Words, an essay by Dr. Lara Sheehi

- The Freedom Theatre in Jenin: Staging a critical form of Palestinian resistance by Hannah McCarthy

Listen:

- shado’s podcast episode on Palestine +100 with Isabella Kajiwara

Visit:

- PalArt Collective’s website

- Artists on the Frontline