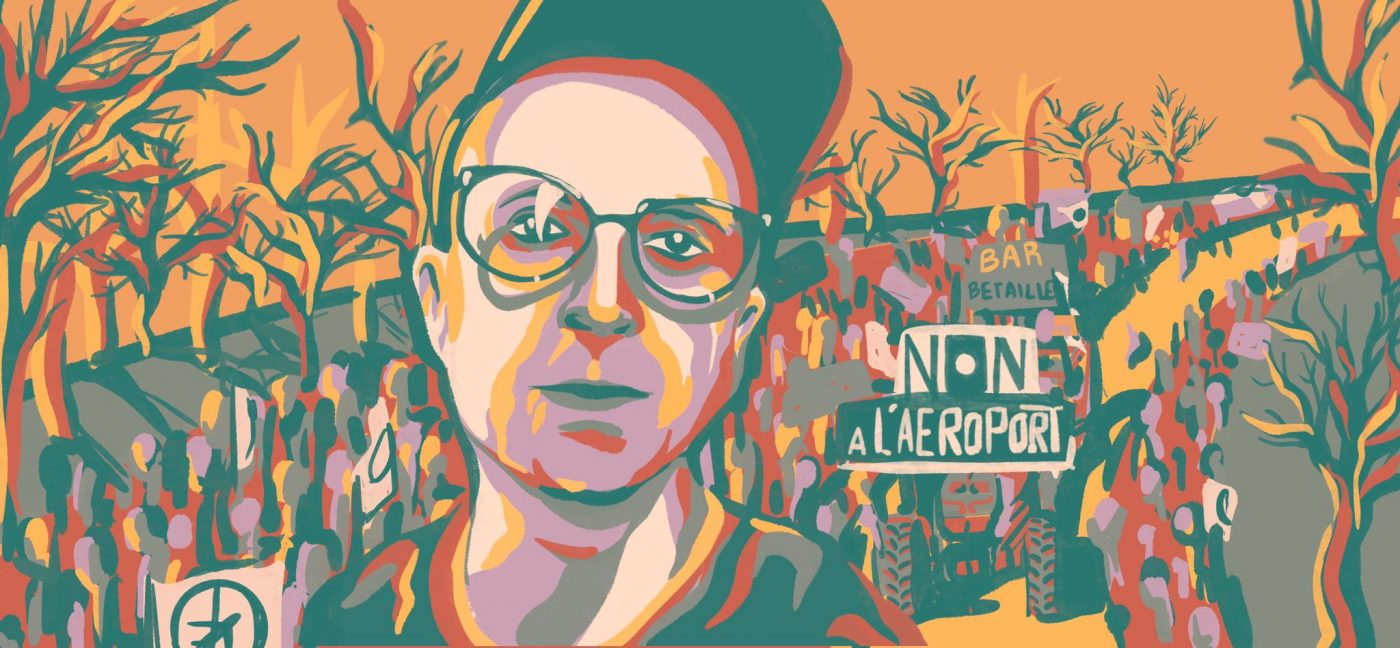

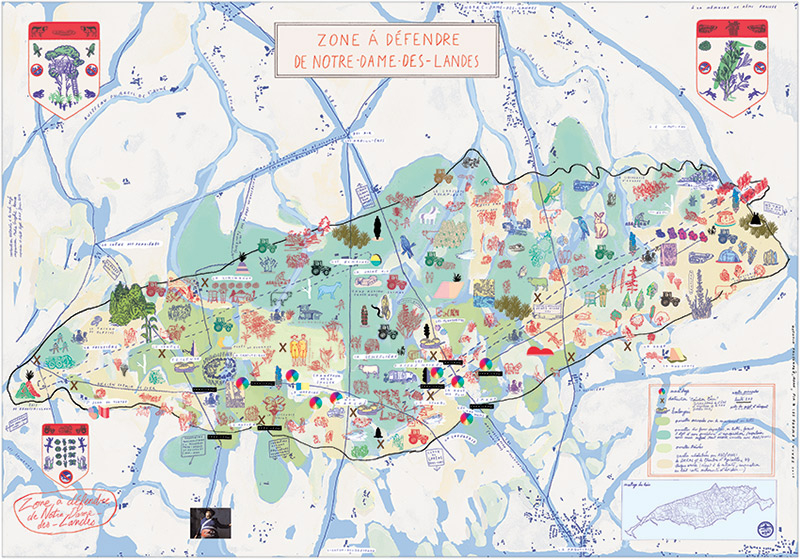

As I speak to artist and activist Jay Jordan, otherwise known as JJ, they are in their home in the ZAD (zone à défendre, or “zone to defend”) in Western France. It’s 4000 acres of wetland, farmland and forest that was originally intended to be built into an airport in 1965 but is now an autonomous territory occupied by 40 different collectives looking to reclaim the land.

The ZAD, which JJ calls a “liberated territory against an airport and its world,” has a rich history of activism, rebellion and direct action. It is an entanglement of resistance and art, imagination and autonomous zones, living utopias and political systems.

The start of JJ’s journey, which would eventually lead them to the ZAD, began in the 90s. Training as a creative in the elite institutions of fine art and theatre, they became frustrated by the lack of political engagement in those worlds.

JJ then began to get involved with squatting and other movements against road building. Rather than fine art, they discovered that these were the kind of ‘performance pieces’ they wanted to do.

Merging arts and activism

In 2004, JJ met Isa Frémeaux, and together they set up the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination to “merge together the courage of actors and the creativity of artists”.

Although they began by helping to support protests and climate camps, JJ came to realise that it wasn’t enough.

“We’d go home, we’d go back to our flats, back to our jobs, and back to reproducing capitalism in our everyday lives,” they explain. “We’d have these little moments where we were living in spite (because you can really never live outside) of capitalism,” but ultimately these were fleeting.

That tension was never fully resolved, but in their quest to bring art and activism into everyday life, JJ and Isa eventually ended up at the ZAD. For them, it was the closest they could get to prefiguring the world they were looking to build.

The ZAD’s history of rebellion and resistance

The history of the ZAD itself is one that spans decades before the arrival of JJ and Isa.

Since 1965, the French state had planned for the area to be an airport. It’s worth noting that even in the 70s, farmers were battling the idea, though more organised forms of resistance didn’t start until 2008 when the first climate camp was formed in France.

In response to the airport proposal, local residents read out a letter declaring that “to protect and defend a territory, you need to inhabit it”. They called on groups to support the cause and squat in the empty farms and forests as an act of resistance.

In 2012, the French state tried to evict the zone, which consisted then of 40 to 50 local farmers who were refusing to sell their farms. Battling against riot police, the people resisted fiercely with songs and tractors. People were fighting from trees, they were burning barricades and they were even using Molotov cocktails.

The residents claimed that even if an eviction were eventually successful, they would just come back. And they kept to their promise, 40,000 people turned up a month later to rebuild what was destroyed by the police.

In three days, they had completed the reconstruction, but the police returned again, with tear gas, explosive grenades and rubber bullets, injuring 300 people.

The attacks only stopped after medical professionals sent a letter to the President urging him that people would die if this fighting continued. And for a while, the residents of the ZAD lived a life without police, without a government, without state planning and control. “We lived with nothing,” JJ says, “except for the forms of organisation that we wished to have.”

Continued state violence

In the years after, they began to build legal cases against the French government. They tried and lost 178 laws, and in 2016 officials declared that because they had no legal grounds to keep the land, the state would go ahead with building the airport.

The people continued with their methods of resistance: first bringing 20,000 people, 1,000 bikes and 500 tractors and setting up a banquet on the bridge which led to the proposed airport.

The state responded with violence once again, with water cannons and orders to clear the bridge. A month later, the communities returned with 60,000 people to block the area, organising entire parties with big sound systems and bands on trucks.

“The government realised that it wasn’t going to be as easy as they thought to defeat us: it wasn’t just a load of squatters, anarchist punks, and old people from the villages.”

At one point, the government even tried to put through a referendum (which JJ says was “completely biased”) with the intention of dividing the movement and causing chasms between the legalist NGOs and anarchists. Despite this, people kept on resisting.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Running the lands as a commons and tensions within the movement

In 2018, French president Emmanuel Macron announced that the plans to build the airport would be shelved, but that the people who were occupying the land had to ‘legalise or leave’ – to which they responded with a proposal to run the lands as a commons.

Macron refused, and in April that year, JJ tells me they came with the biggest police mobilisation in the history of France since May ‘68: 4,000 police drones, tanks, helicopters, tear gas and explosive grenades.

At this point, there were major, deep splits within the movement around whether the land was to be legalised or not. Those who didn’t agree to it had to leave, and those who did, stayed.

“We’re still fighting to turn this land into a commons,” JJ says, in alignment with an original document written by activists and farmers in 2014. “It took 40 years of action to defeat the airport proposal, so maybe it will take 40 years to return this land back to the commons that we want it to be.”

Rebuilding and the path ahead

Today the work to do that continues, alongside the work of rebuilding, slowly, what was destroyed in the massive counter-mobilisations from the government. “There’s a lot of building going on at the moment”, JJ continues, “even though we don’t actually have planning permission for any of those buildings. It’s still a big negotiation with the government.”

Upon reflection, JJ explains that the ZAD has “never really had one way of doing anything.” It has always been “very decentralised, complex and diverse,” which JJ believes has been “both our strength and our weakness, in a way.”

Resistance is messy. Diversity of tactics, and the variety of groups involved, meant that when the people fought back against the state, they sometimes won because the state could never pin them down, and there were always other groups coming up, one after another. But the diversity was a weakness too: in the end, disagreements over legalisation brought about splits within the movement.

In the aftermath of the decades of fighting, and as the dust is settling, it’s clear that resistance has not been so clear-cut. There were victories—after all, the airport was never built, the land was never left unoccupied—but there were also failures.

JJ would be the first to acknowledge that. The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination is so-called because “our projects are experiments, because we think everyone should have the right to fail.” They add that: “We don’t believe in overnight revolutions; we believe in an insurrectionary process, that of rising up and then merging that into everyday life.”

This kind of thinking shows us that another world is possible, but it’s not going to be a perfect one, and it’s not going to be an entirely autonomous utopia. As JJ says, the ZAD is not an eco-village, and it never meant to be. You can never live outside of capitalism: we live in spite of it.

As French poet and Surrealist Paul Éluard said: “There is another world and it is in this one.” Another world is possible, and it will rise through the cracks and folds of this one. We will resist this world, and while doing so prefigure a new one alongside it. This absence of a perfect utopia is not a reason to despair. In fact, it’s something to celebrate, because that means we can, and have been, building new worlds, as we speak.

What can you do?

- Read the full version of this interview with JJ on Advaya’s website

- Read the story of the ZAD, as told by Jay Jordan and Isabelle Fremeaux

- Read more about farmer led social movements HERE

- Find out about climate justice in shado ISSUE 03

- Don’t ask what you can do: find others who are asking these questions, and don’t do it alone.

- Go back to joy: as JJ says, “If you want it to be regenerative, there has to be pleasure in changing the world. If it’s boring, then we’re never going to get anywhere.”

- Find an attachment and refused this “detached floating culture of neoliberalism”: freedom comes because we’re linked to each other, it’s not to be an individualised atom.

This is a series of articles co-published by Advaya and shado, in advance of Regenerative Activism 2022: a series of live online events, including three panels and one participatory workshop, featuring 11 incredible speakers, including activist and environmental lawyer Farhana Yamin, farmer and land rights activist Jyoti Fernandes, co-executive director of Green New Deal UK Fatima Ibrahim, lifelong activist Satish Kumar, and more. The event series will explore radical imagination and reclaiming the future. All sessions will be recorded and made available upon registration. Find out more and register here.