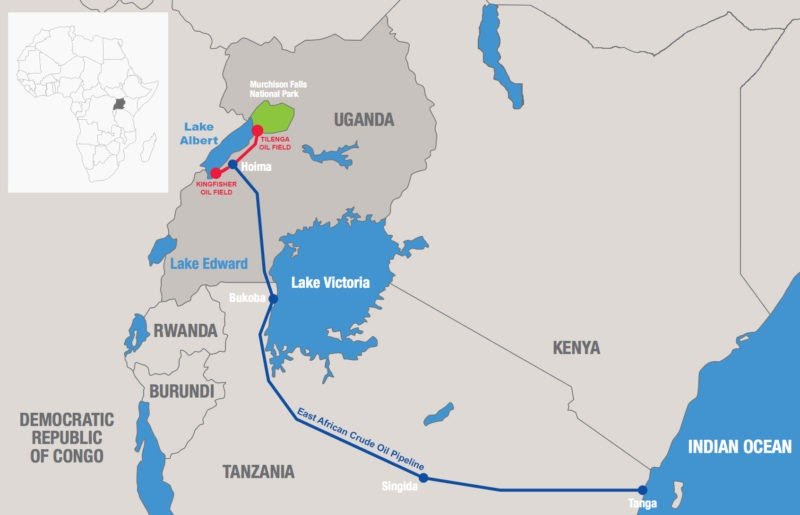

The East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) in Uganda and Tanzania is a major environmental threat to some of the most delicate ecosystems in the world. The project is being developed by French oil giant Total and the Chinese National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC). At 1,445 kilometres (900 miles), it will be the longest heated oil pipeline in the world and emit more CO2 than all of Uganda and Tanzania combined – which will undeniably come with catastrophic consequences.

The threat of fossil fuel investment in East Africa

I became involved with the Stop EACOP campaign when I met Omar Elmawi, one of its coordinators, through my work with Stop Cambo at COP26. He had come all the way from Kenya to spread the word about what was happening in East Africa and to demand climate justice.

At the gates to the conference, he held a powerful speech stressing that there must be an end to the use of fossil fuels in a world with climate change – “not here, not anywhere”. Since then, the two campaigns have partnered to highlight that the fight against fossil fuels is a global one.

Recently, the governments of Uganda and Tanzania, alongside the main stakeholders Total and CNOOC, announced the final investment decision for EACOP. It was met with a statement signed by fifty NGOs from Uganda and DRC, urging governments to invest in green industries instead of fossil fuels.

Room for manoeuvre

Speaking to Omar about the recent announcement, he says: “It’s definitely a milestone for the project. 40% of the financing is supposed to come from equity and around 60% from outside loans. Currently, the government has said they are serious about proceeding – but they didn’t disclose whether they’ve secured all the funding they need to go ahead with it. We think it’s unlikely; the announcement seemed more like a way to bring publicity to the project, make financiers interested. But it also means that it’s now at that critical juncture where we have to escalate our organising to try and stop EACOP.”

I’m surprised by his take, as many media outlets portrayed the recent developments as if the pipeline was now definitely going ahead. So it’s still up in the air, I ask?

“Exactly”, says Omar, “and recently, four of the five biggest banks in South Africa have committed to not invest in EACOP. Around the same time, Total announced the biggest profits ever seen by a company in France (around €13 billion). It’s interesting to look at the discrepancy between their profits and how the countries they operate in are faring.”

What threats does EACOP pose?

This brings us to the crux of why EACOP is so problematic. Much of the project will be financed with loans, while Total will cash in most of the profits. There is a real danger that Uganda and Tanzania could actually end up with more debt than they had before. I ask Omar whether he agrees with the many campaigners who accuse Total of perpetuating neocolonialism in East Africa with its extractive ventures.

“Yeah, that’s definitely true. Just look at how the deal is structured: Total and CNOOC have 70% ownership of the project. The governments of Uganda and Tanzania have 15% each. Those who profit the most take the least risks, because it’s the people of Uganda and Tanzania that are exposed to all the impacts. If there are any health impacts and people need to go to the hospital, or if there’s an oil spill in the Lake Victoria region – it’s not Total who will bear those costs.”

No accountability for exploitation

I’m in disbelief. So they don’t even have to pay for cleaning up oil spills?

“There’s no law covering this. They’ve even passed new laws to give Total a tax holiday for 10 years. The project spans 20 years, so for half of it they won’t be paying any VAT or corporate income tax – and in that time they can extract as much oil as they want. Some of those laws are even infringing on constitutional environmental safeguards. They’re passing a law which enables corporations to extract those resources without taking any responsibility once they’re done. It’s a huge problem. They’re selling it as a “game changer” for Uganda and Tanzania – but it’s more of a game changer for Total. And they will just continue to make more and more profit.”

Concerns of the local community

There are a number of concerns surrounding the project, and not just from environmentalists. Uganda is already experiencing the effects of climate chaos – such as floods, droughts, and crop failures – and it is probably already too late for an oil boom, given that the majority of the global economy has committed to decarbonisation. There is a real risk of stranded assets – economic devaluation due to a fall in demand – as the world moves away from fossil fuels.

But the real threat comes from the pipeline itself: running through multiple protected wildlife habitats and along Lake Victoria (Africa’s largest lake), the risk of oil spills cannot be understated. The project has already led to land grabs from local communities in Uganda, and tens of thousands could be displaced to make space for infrastructure, roads, and a new airport. Those displaced are being sent to temporary housing, where they are suffering from cramped conditions and human rights violations.

On the social effects of the pipeline, Omar comments: “It’s a really, really long pipeline. It’s going to affect people significantly, especially those who live on the land. Some of them have already been displaced. They’re losing their homes and livelihoods, because a big percentage depend on the land for farming. Seven out of ten people in Uganda are employed in the agriculture sector, so it could affect 70% of the local working population. More than a third of EACOP will be located within the Lake Victoria water basin, which is a source of freshwater and food for more than 50 million people – with no alternative. If an oil spill happens, those communities will be affected the most.”

He continues, “There’s also been issues around security. The government has been aggressive in pushing through this project. Anyone speaking up against it could find themselves being arrested. We’ve seen organisations being threatened to have their licences deregistered. And there’s many other examples.”

But despite constant intimidation and threats, the campaign is going strong. “Our messaging is now focusing on who will be the biggest winners if EACOP goes through, and who will be the biggest losers,” Omar explains. “We are also targeting banks because this project is expensive. The current participants cannot foot the bill – they need lending. So we’re pushing them to commit to not investing in EACOP. So far, it’s working: 15 of the 27 banks we’ve approached have confirmed that they won’t be proceeding with the project. And therefore we have hope that there’s still a chance of stopping it. We are also targeting financial advisors and insurance companies, questioning their climate leadership.

Solidarity and the need for international awareness

But most importantly, we’re trying to escalate this issue on international platforms. Hopefully more and more people will see the wrongdoing that’s being perpetrated in Uganda and Tanzania in the name of ‘development’.”

Stop EACOP has huge international support; French and Ugandan NGOs have taken Total to court over its human rights violations last year. The case was dismissed, but the groups are appealing – with the hope that the oil giant will be forced to take responsibility for its actions.

In the meantime, there are lots of ways we can help remotely: “People can pray for us, but they can also take action”, Omar says. “You can donate to support our community partners in Uganda and Tanzania, so they’re able to be consistent with the work that needs to be done. You could sign our petition pushing stakeholders to drop the project, which has around 1 million signatures so far. On our website, you can send an email to the banks and insurance companies we’ve been targeting.

People can also help by following our Twitter and Instagram pages and sharing our message. You can take a photo with a ‘Stop EACOP’ sign and tag us. We want to show that this campaign is not just a few people who are opposed to development, but a global campaign that’s being driven by communities. Because it’s an injustice to all life.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

When asking whether Omar has a message to people reading this article, he stresses: “We should not be looking at fossil fuels as a vacuum, without considering the bigger picture. People should be just as concerned about fossil fuel projects in Uganda as those in their own backyard. People in the UK, for example, should be just as bothered about EACOP as they are about the Cambo oil field. We need to build an understanding that we must fight all fossil fuel projects – not just in our own countries, but around the world. Once we are able to do this, then we can claim that we are genuinely taking climate action.”

What can you do?

- Follow the EACOP campaign on Twitter

- Follow the EACOP Instagram page

- Sign the petition pushing stakeholders to drop the project,

- Send an email to the banks and insurance companies

- Donate to support the campaign’s community partners

- Find out more about Stop Cambo HERE