Slavery has taken a modern turn in today’s world. Under the umbrella of the Kafala system and rulership of corrupt political elites, many countries are claiming to provide “opportunities” for domestic workers to earn income outside of their country, whilst in reality they are faced with inhumane conditions and the absence of legal protections.

This situation has led to the creation of several movements and groups to help raise awareness, provide humanitarian aid, fight for accountability and the abolishment of the Kafala system.

The Kafala system is a sponsorship system used by citizens of a country who wish to employ a migrant worker for a specific short-term purpose. The host citizen (sponsor) is responsible for the worker’s legal status, visa and protection. It was established in the 1950s within several countries in the Middle East and is still used today as a tool to maintain the oppression of migrant workers.

The Kafala system in Lebanon

During the 1970s, when the first immigration wave to Lebanon from Africa and Asia began, a Kafala system was designed to hire individuals from these marginalised groups to work for Lebanese citizens.

Lebanon continues to support this exploitative system by excluding migrant workers from Lebanese labour laws. Currently workers under the Kafala system are not guaranteed a minimum wage, don’t have maximum working hours or vacation days, and have no rights or social security.

Workers are also not allowed to leave or change sponsors. When the contract period is over, workers are either forced to continue working under these conditions until their contract is renewed or extended, or it ends – resulting in the immediate deportation of the worker.

To add to the precarity of the situation, workers are often trafficked into the country by agencies that work as mediators for employers in host countries. And it has a disproportionate impact on women; according to the International Organisation for Migration, “367 females, between 2020 and 2021 alone, were victims of trafficking in Lebanon, though this does not capture the full extent of trafficking into the country.”

What is Egna Legna?

Egna Legna (Us For Ourselves) is a domestic worker-led organisation and political movement established in 2017. It identifies as a feminist organisation and aims to support domestic workers trapped within the Kafala system.

The organisation provides direct humanitarian assistance to migrant domestic workers, raises awareness of violence and abuse, and works to protect the sexual and reproductive rights of migrant workers. One way in which they do this is by hiring lawyers to advocate for the abolition of the Kafala system in court and they also work in schools and online to raise awareness about the injustices within the system.

Egna Legna also operates in Ethiopia to help migrant workers who escaped Lebanon’s Kafala system. They help workers return to school to learn new skills as well as providing financial assistance and psychological support for women who have been sexually abused or suffer from depression. They have also started to build their own school in Ethiopia to raise awareness about the Kafala system.

Lived experience leadership

I spoke to Banchi Yimer, the founder and director of Egna Legna. Banchi is a former migrant domestic worker herself who left Lebanon in 2018 after being overworked and underpaid for a period of seven years.

Banchi begins by telling me: “The Kafala system is a modern form of slavery. It’s like someone sending us to prison when we haven’t committed any crime”.

She explains the terrible living conditions she experienced while in her sponsor’s house: her bed was on a closed balcony next to the kitchen with no heaters, and water would leak from the ceiling onto her pillow.

A study by the international Labour Organisation (ILO) back in 2016 shows that only 16.4% of employers pay $300 or more; with 30 employers (about 2% of the sample) reporting that they paid workers less than $150 a month. The legal minimum wage back in 2016 was $450 per month, but because domestic workers are not covered by the national system, this discrimination went unchecked.

Banchi’s struggle was not purely financial. She also suffered psychological stress from racism, sexism and discrimination in her day-to-day life. These abuses pushed her to establish Egna Legna to help other migrant domestic workers and raise awareness of the Kafala system in Lebanese society more widely.

Abolition and accountability

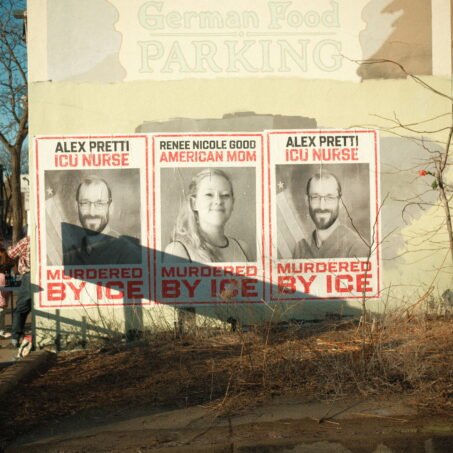

It becomes clear from talking to Banchi that abolishing the Kafala system will not be enough on its own however and that instead, “the biggest obstacle is accountability”.

Currently, employers are getting away with abusing and mistreating their migrant domestic workers without facing any consequences for their inexcusable human rights violations.

Countless cases detailing unpaid wages, the seizure of passports and identification papers, physical, emotional and sexual abuse have been reported by migrant workers, but these are routinely ignored by the Lebanese authorities.

Banchi tells me, “We have heard lots of reports of women being locked inside their employers’ houses despite committing no crime. These women were denied their salaries and were not allowed to go home or communicate with their family.”

A Human Rights Watch report back in 2008 found that migrant workers were dying at a rate of one per week, with suicide and attempted escapes the leading causes of death.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

10 years later, despite this shocking report, Human Rights Watch found that Lebanon’s judiciary is continuing to fail in holding employers accountable for abuses and that “security agencies often did not adequately investigate claims of violence or abuse.”

Using Lebanon’s liquidation crisis as an excuse for abuse

The number of workers being exploited through the Kafala system has escalated over the past two years after the country entered its devastating socio-economic crisis. There are now an estimated 250,000 domestic migrant workers in Lebanon and this number is set to increase.

Lebanon entered a dark era as its currency started deteriorating in 2019. This was worsened by the devastating Beirut port explosion which killed over 200 people, injured more than 7,000, and crippled the country’s import and export capabilities. By the end of 2021, the Lebanese pound had lost 82% of its value.

The liquidation crisis was used as an excuse by employers not to pay domestic workers. Some families threw them out on the streets, most of the time without their belongings, money or passports.

Banchi tells me that more than 1,000 workers have been reported to have had to sleep on the streets in 2021. “Some of them were sleeping in front of their embassies,” she adds.

In one shocking case, a sponsor shared a post on a Facebook group page for second-hand items. It was captioned “for sale” and showed an image of a Nigerian domestic worker. It was only after the pressure from multiple media reports and heavy coverage that the Lebanese authorities arrested the employer.

The lack of protection for workers leaves them trapped in a vicious cycle of exploitation and discrimination. “We are not talking about citizenship or better education or better jobs,” Banchi explains. “We are talking about survival.”

Failures of the Lebanese justice system

Not only has Lebanese society failed to protect migrant workers but so has the judiciary.

Many cases of false accusations such as “theft” and “attempted murder” by sponsors have led to the imprisonment of workers with sentences which vary between two to six years.

Because of the inhumanity of the Kafala system, workers have no right to leave or change their sponsor even in cases of abuse, and calling to complain to the authorities is useless because they will largely be ignored or risk deportation.

“One woman who I’ll never forget,was mentally and physically abused, suffered from severe depression. She had been exploited and received no pay for three years. This woman was so badly traumatised by the experience that she now doesn’t even remember her own name.”

Some legal cases have been assigned to lawyers by community movements and organisations such as Egna Legna and there have been some successes where women have been released. However, sponsors continue to face no consequences for their actions which leads to a never ending circle of violence.

In February 2021, some progress was made when the Lebanese General Security issued a decision to no longer allow sponsors to file criminal complaints against migrant domestic workers for ‘running away’. This was a huge step after years of protests and movements by migrant communities. However, domestic workers still continue to face false accusations by employers who use their authority to continue oppressing migrant workers.

This is why accountability is a key factor in the current movement and work of organisations like Egna Legna – because without justice for past and current abuses, we won’t be able to prevent future crimes.

The disproportionate impact on women

Migrant women make up the majority of people who come to Lebanon as domestic workers.

While they technically have the legal right to terminate their contract if their sponsor subjects them to physical or sexual violence, this rarely happens. According to a 2020 ILO report, this is because “there is still no state-mechanism for a domestic worker to file for her contract termination – neither internal protocol nor personnel to investigate, administrate or conduct the termination process.”

The Kafala system is both racist and an act of patriarchal control over women. Fighting for its abolition and demanding accountability is the only solution – and Egna Legna is a clear example of what intersectional feminism should represent and fight for.

Limited support

There are many groups and movements supporting migrant workers in Lebanon. However, like Egna Legna they have very limited resources as they are often grassroots organisations which limits their capabilities.

One large barrier to effective operation is the fact that the organisation is not allowed to be registered within Lebanon. Although Egna Legna is registered both in Ethiopia and Canada, it can not currently be registered within Lebanon if the majority of its board members are not Lebanese nationals.

“It’s a struggle and we have to find the resources and take on big budget projects including campaigns with migrant community people and politicians,” says Banchi.

“How can we propose policy or research for the government? We are unable to do so many of the things that we do in Ethiopia and Canada because we are not allowed to be registered in Lebanon”.

Most community groups and movements in Lebanon are either led by Lebanese nationals or men – despite the fact that women make up an estimated 76% of all migrant workers and 99% of migrant domestic workers who come to Lebanon for employment.

“I have nothing against these groups but we want to represent ourselves, we don’t need anyone to speak on our behalf” explains Banchi.

However, if Egna Legna recruits more Lebanese nationals, in order to access more resources, it might jeopardise the safety of the migrant workers and the decision making within the group because it will no longer be an organisation run by migrant domestic workers.

“We have raised thousands of dollars to support migrant workers but the problem is a lot bigger than this. We need greater support from the international community.”

Protesting to end the cycle of abuse

Through talking to Banchi it becomes clear that the Kafala system must be abolished but without holding those that uphold it accountable, the cycle of abuse will continue.

Although the Lebanese General Security have made progress by introducing new laws including that sponsors have no right to keep the passports or identification papers of their employees, this has not stopped the violence and abuse against workers.

“Our aim is to support workers who have been abused by the system. I cannot say their lives will ever be normal again but our aim is to at least make their lives a little happier. And accountability is so important for this.”

Migrant communities have been protesting alongside Lebanese people and other feminist movements, fighting for their rights to abolish the Kafala system and demand accountability which has successfully imposed pressure on the society and we have seen authorities start to act.

We have noticed a significant change within Lebanese society and specifically from Lebanese women who started participating more in the movement. While it is in recent years that we have seen the movement become more mainstream and real progress has been enacted, this would not have been possible without brave individuals and organisations like Egna Legna who have been fighting against this system for decades.

The journey of resistance

Lebanon has seen the migrant domestic workers communities uniting and protesting the Kafala system for years.

In one example, in 2020 Labour Minister Lamia Yammine drafted new legislation to ease the Kafala system with a standard employment system that guarantees and protects the rights of migrant domestic workers.

However, in October of the same year, after a complaint was issued by recruitment agencies (mediators of the Kafala system) the state Shura council, the country’s top administrative court, suspended the legislation. They said it caused “severe damage to the agency’s interests”.

Reflecting on my conversation with Banchi it is clear that the Kafala system in Lebanon is racist, sexist and oppressive in nature.

The Lebanese justice system has failed to protect migrant domestic workers and has proven to be a collaborator in wider institutionalised structures which are oppressing and exploiting migrant workers. The unwillingness of the Government to hold those perpetuating the system accountable means that oppression will not simply end if the system is abolished.

We have seen the disproportionate impact of the Kafala system on women and how the Lebanese liquidation crisis is being used as an excuse to perpetuate abuse. In addition, the limited support migrant-domestic workers receive in Lebanon even from organisations like Egna Legna due to their limited resources, does not scratch the surface of dealing with this sort of oppression.

The fight for migrant domestic workers’ rights is a big part of the intersectional feminist movement in Lebanon, that stands for all marginalised groups’ rights regardless of their backgrounds. “I’m a woman first and a feminist at the same time”, Banchi tells me.

Although the fight is hard and long, there has been a significant increase in the support for migrant domestic workers. This can be seen by the increasing participating number of Lebanese women in the protests and movements during the past few years. This support is the fruit of awareness raised by organisations such as Egna Legna and the movement is only going to strengthen going forwards.

What can you do?

- Donate to Banchi’s GoFundMe, providing Kafala workers with food and medicine

- Follow Egna Legna on Instagram

- Read more about the Kafala system HERE

- Listen to The Fire These Times episode with shado editor Elia J. Ayoub and Banchi

- Follow the Migrant Community Centre on Facebook

- Read more articles about intersectional feminism HERE