Afrofuturism is a reimagining of the reality of the African diaspora through the prism of science fiction and fantasy. It is a celebration and imagining of an Afrocentric world in which African ways of being have room to envision the future.

Afrofuturism has roots in the African diaspora experience. However, it can represent the ideas of collective remembering and reimagination required throughout Africa and its diaspora to reinvent a cruel past.

Eleven modern African diaspora artists are featured in the Hayward Gallery’s In the Black Fantastic exhibition. Ekow Eshun, the curator of the exhibition, mixes science fiction, mythology, and Afrofuturism to offer new insights into various facets of our existence as Africans.

How Eshun seeks to distinguish between the continental and the diaspora Africans was a topic of discussion during the press viewing of the show I attended last week. This made me consider how I define Africanness and who is entitled to Africa.

I struggle with this since I am both an African from the continent and an African living in the diaspora. As Eshun pointed out in his response however, we should refrain from essentialising the concept of Africa or its diaspora since Afrofuturistic artworks comment on what we can be rather than what is. They do so by reimagining African existence. Drawing a line between African artists and those from the diaspora is not the point.

The artists, regardless of their geographical locations and how it might have affected their experiences, all collectively explore a diasporic condition that arises out of a historical relationship with the ways we, as Africans at home and in diaspora, have found ourselves existing as a result of forced migration, slavery, and colonialism. Eshun explains: “Africanness is a hybrid condition.” Many of us have ambiguous identities, existing somewhere in between.

In the Black Fantastic beautifully illustrates the connection between Africa and its diaspora and these hybrid and collective existences that (can) exist. The artists use the folklore, mythology, and cosmologies of Africa, proving that regardless of their location, Africans in the diaspora have both access and a right to these systems.

I started considering the value of collective memory in imagining potential futures. Afrofuturism can be seen as an act of collective memory that examines the future through the lens of the past. The concept of collective memory becomes even more crucial when we consider how generations can remember when their cultural archives, histories, and memories are destroyed through forced relocation, migration, and slavery.

This is especially true for Africans in diaspora, but it is frequently overlooked that Africans living on the continent also had their cultural records, histories, and memories destroyed and altered.

Continental Africans are likewise rediscovering and reimagining their cultures and histories, which have been obscured via a Western viewpoint. Therefore, rather than recreating pointless essentialised categories, this must be a collaborative effort amongst Africans on the continent and in the diaspora. We are on this journey together.

Nick Cave’s Chain Reaction features resin casts of the artists’ arms clutching each other. This is likely the first piece you will see when you enter the exhibition, and it perhaps best illustrates the collective action of us working hand in hand. It prompts how you should view the remaining artworks – via the lens of collective memory. It also serves as a reminder of why you are visiting the show. The paradigms and understandings that liberate us to conceive alternate realities are drawn from Africans in the continent and diaspora working collectively.

The strategic use of art in this collective remembering and reimagining stems from the visual arts’ capacity to challenge, explore, speak to, and produce collective experiences beyond our everyday modes of existence.

Through art, memory is transformed into a narrative and story that is not limited by the requirement for fact or an exact imitation of an experience. The representations need not be evidence of anything; instead, they are just stories of people’s collective reimaginings. The erasure of the violent experience of Africa manifests itself in visual art as a fresh mode of representation that veers away from history’s linear logic and oscillates between memory and history.

In Ellen Gallagher’s Watery Ecstatic and Ecstatic Draught of Fishes, we see images of the descendants of enslaved pregnant women who were thrown overboard during the ocean crossing from West Africa to the Americas.

These descendants are shown in Drexciya, a mythical underwater Black Atlantis. It doesn’t matter if this vision is plausible or realistic; what matters is that it represents an imagination drawn from a complicated past of suffering and tragedy to remember and reimagine. It is about how this ostensibly impossible piece, while offering optimism through reimagination, enables us to see elements of African history that are frequently erased.

Afrofuturism is not about trying to be truthful and realistic through these arts; this requirement is inappropriate for the liberation we want. Our memories should be able to recall historical accounts, customs, and ways of life that various types of colonialism have imperilled. We should use these to envision potential futures, not ones based on our current realities.

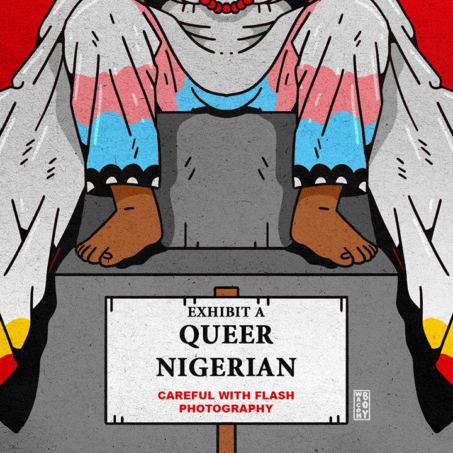

This reminds me a lot of queer politics, which seeks to break free from normative institutions. Since similar ideas ultimately inform both queer politics and Afrofuturism, I find it impossible to discuss Afrofuturism without bringing up some form of queer politics.

Most of the artists featured In the Black Fantastic reference queerness in their works, and it was a pleasant surprise to realise how queer this exhibition is.

Build or Destroy, a film by Rashaad Newsome, is possibly my favourite installation at the exhibition. This short film is made up entirely of queer chaos and joy. Not “queer”, as in, synonymous with LGBT, but “queer”, as in, a radical departure from, and deconstruction of, normative and violent structures of gender, race, class and power.

The music accompanying the film isn’t just peppy and enjoyable; it’s a manifesto for envisioning queer possibilities that destroy all oppressive systems. White supremacy, patriarchy, gender norms, and class oppression are demanded to be destroyed in the lyrics. The demise of all these systems is depicted in the background as a figure, giving post-apocalyptic realness, vogues over the carcasses of these violent, repressive systems.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

The film’s end reminds us that “being trans is not just about reimagining the body. It is about bearing witness to the structures around us and detonating them.” It is more concerned with blowing up these violent structures and revelling in the wreckage than being represented or participating in them. Although it may appear to be a gloomy picture, I assure you it is one of hope.

Tabita Rezaire’s film, Ultra Wet – Recapitulation, exquisitely projected onto a pyramid, does the same thing by having seven narrators implore us to think of ourselves outside conventional gender constructs. For Rezaire, “a world of them and us – whatever the criteria – will always breed more violence and suffering.”

The narrators explore this by bringing our attention to pre-colonial African conceptions of gender that were less binary and more accommodating of what are now considered ‘deviant sexual identities’. Understanding our past might help us imagine what is possible for the future. If we remember that there was once a time we did not exist in binaries, the idea becomes less abstract and can be conceived for our futures.

The artists at In the Black Fantastic offer a refreshing take on Afrofuturism and alternative ways of being for Africans. They do not homogenise Africa or reduce its cultural practices to a mere aesthetic in their artistic endeavours.

They are clear about which aspects of the diverse African cultures they are drawing inspiration from and how these are relevant to the stories they are telling. They provide insightful reimaginings beyond the reductive idea of Africa as popularised by diasporic celebrities as a continent populated entirely by kings and queens of a land of honey and gold.

I’ve had to come to terms with the legacy of reinventing African consciousness, which has often been normative and rife with hetero-patriarchal, classist, and individualist ideas that do little to dismantle the systems that have often restrained Africans. It is a misconception that violent structures do not occasionally reappear in our imaginations to imagine future systems based on our present realities.

Therefore, we must actively take steps to ensure that we critically examine these violent structures in our reimaginings, rather than merely reiterating Western ways of being through African bodies. It is neither an alternative nor an imaginative reality if it simply changes the individuals in positions of authority. In the Black Fantastic serves as a reminder of this.

What can you do?

- Visit the exhibition In the Black Fantastic, open until the 18th September

- Listen to the podcast: Re-Queering and Reconceptualising the work of Rotimi Fani-Kayode.

Books

- Read: Pedagogies of Crossing: Mediations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred by M. Jacqui Alexander

- Read Where Memory Dwells: Culture and State Violence in Chile by Macarena Gómez-Barris

- Read The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses. by Oyeronke Oyewumi

- Read What Gender is Motherhood? by Oyěwùmí, Oyèrónkẹ́

- Read Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples by Linda Tuhiwai Smith

- Read The Vietnam War, The AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Read. Decolonization and Afro-Feminism. Tamale, S., 2020 1st Edition ed. Ottawa: Daraja Press.

Articles

- Read: Zepeda, S. J., 2014. Queer Xicana Indígena cultural production:Remembering through oral and visual storytelling. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(1), pp. 119-141.