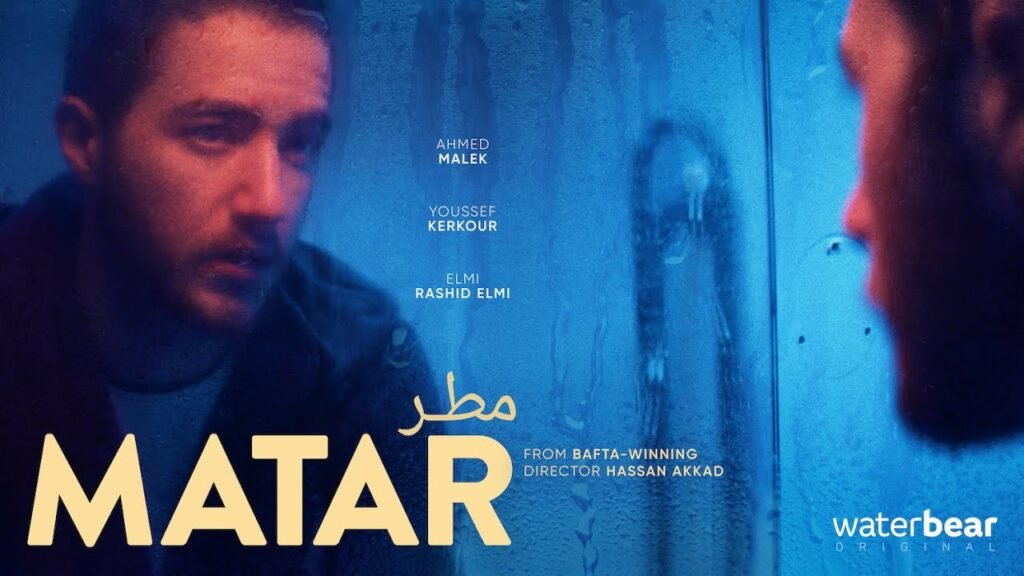

I’ve had the sounds of Arabic-language hip hop artists Blvxb and Shabjdeed pretty much on repeat since I first watched Matar, Hassan Akkad’s latest short film following the experiences of a young refugee in the UK.

The soundtrack to the film was one of my favourite things about it, providing the gritty backdrop for a story about a young man on the grind on the streets of London. Refugee status aside, Matar could be the story of any twenty-something man on a hustle, his trajectory through the city defined by the ‘ping’ of one food delivery notification to the next.

When I meet with Hassan to discuss the film, he describes to me why the casting of a young man in the leading role was such an intentional choice.

“It’s because young male asylum seekers are often criticised in the media,” he explains.

He’s absolutely right: in what often seems like an attempt at distraction, young men are often decried by right and centrist tabloids as “fake asylum seekers” or “economic migrants” hoping to trick the system – as though our system were at all fit for purpose in the first place. Our nation’s obsession with perpetuating this distinction leads us astray from the real issue at stake.

Matar’s reason for claiming asylum in the UK is irrelevant, and purposefully so: the point Hassan is making is clear. Why should any person, whether fleeing poverty or persecution, who is so desperate for a better life that they would risk the dangers of overland journeys or sea crossings, be denied the right to agency?

Watching the film, I was amazed at the level of empathy and character depth Hassan and his team, including a stunning performance by Ahmed Malek as Matar, managed to create in less than half an hour. Its scenes are as much about the unsaid as what’s right in front of our eyes. The film is beautifully shot; masterful, even, in its portrayal of Matar’s quotidian within the context of the systemic barriers he faces as he navigates his journey from asylum seeker to refugee to undocumented worker.

The focus on food delivery drivers is important. I challenge you to find one person in London who doesn’t, even just occasionally, cross paths with someone who works in the gig economy on which the city depends.

While not all gig workers are undocumented, of course, this film reminds us that undocumented people, so often overlooked, are usually the lifeblood of the economies of richer nations. This is overwhelmingly because they are limited to lower paid, informal jobs hastily deemed ‘essential’ by the verbiage of the COVID-19 pandemic, whether they are cleaning our workplaces, picking the fruit that ends up in restaurant kitchens or sewing the garments we order online without a second thought. Matar zooms in on a refugee experience that is neither unique nor spectacular.

“I didn’t want to make a film about a superhero. What about the everyday refugee or asylum seeker? But I also didn’t want to make a 2D character,” insists Hassan.

If popular discourse were to be believed, then all people seeking asylum would either be criminals or geniuses. The latter crops up regularly in a refrain that you often find among those who disagree with restricting asylum seeker intake, and one that perpetuates the dangerous myth of meritocracy: the idea that we might be shutting the door on talented doctors and nurses who could reinforce our failing health system, or engineering brains who could add value to our country’s businesses, or even potential Olympic athletes.

While all of this is arguably true, don’t delivery drivers deserve to be treated like human beings, too?

I would be remiss, of course, not to mention The Swimmers, released in cinemas in 2022 and most recently on Netflix to critical acclaim. Indeed, Hassan himself was involved in production of the film along with his Matar co-writer, Ayman Alhussein, and Matar actors Ahmed Malek and Elmi Rashid Elmi.

“The story of Yusra and Sarah Mardini is an amazing one, and it’s an amazing film,” Hassan assures me. “But that’s why I then needed to tell the story of someone like Matar.” He goes on: “There is so much focus on the journey that people take to Britain but there’s hardly anything on the one they take once they’re in Britain. And that journey is now becoming more and more difficult.”

Other than the fact that he speaks Arabic, we know nothing of Matar: not his backstory, his country of origin, nor how he came to the UK. Hassan explains to me that he was keen to avoid giving Matar a nationality because of what he describes as the “hierarchy of the refugee world.”

In many ways, he could be any refugee throughout history, reminding us that, from the Holocaust to the Vietnam War to the present day crises, there will always be a need for safe haven on international shores.

However, Matar’s relative anonymity is also reminiscent of the homogenising lasso that mainstream media often loops around refugees: they’re a monolith, each of them with the same experiences, whether they’re from Afghanistan or Eritrea. This kind of narrative leaves no room for the layers of humanity that are critical to consider in the design of any policy around asylum seeker intake.

This film is as much about London as it is about our broken asylum system. The theme of surveillance is unmissable – indicated not through screenplay but through the use of body cam shots and CCTV footage, a clever use of medium in a film that’s only 23 minutes long.

But it speaks to another phenomenon that many people in Britain’s capital will understand well: for all its bustle, opportunity and diversity, London can be a painfully isolating and lonely place.

One scene in particular that endears Matar to his audience sees him making a delivery to a house party in a block of flats. The customer barely acknowledges him – none of them really do – but after the door is closed in his face, there’s a defeated longing hanging in Matar’s expression as he rests his forehead on the wall, as if trying to absorb the muffled sounds of music from the party into his own body.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

It’s this layer of humanity that most people tend to forget in our media narratives on refugees that focus purely on the journey, on the trauma, and on the struggle: that once upon a time, many of these now-refugees enjoyed house parties too. They argued with their siblings over trivial matters. Changed their outfits several times before going out to meet friends. Spent too much time looking at screens instead of books.

I’ve been following Hassan for a couple of years now, ever since I saw his giant face projected onto the white cliffs of Dover as part of a campaign by the activist group Led by Donkeys 2020, imploring the British public to see asylum seekers as people. The initiative was launched in response to the then Home Secretary, Priti Patel, launching her latest diatribe against small boat crossings, in a vague attempt to steer attention away from the government’s pandemic mismanagement. Since then, we’ve acquired a different Home Secretary, but one who’s still hell-bent on developing policies to raise the drawbridge on Fortress Britain.

The Illegal Migration Bill, or the “Refugee Ban” as it’s dubbed in activist circles, is legislation to immediately remove – to a “safe” third country like Rwanda – any person who comes to the UK via irregular routes such as small boat crossings.

The Bill has been defended by its supporters through an insistence that our country is, in fact, a welcoming place for migrants – as long as they respect the rules and come via an official route. Current Home Secretary Suella Braverman is fanatically trying to push the Bill through Parliament, despite the fact that it very likely breaches various international legal conventions, such as the European Convention on Human Rights.

By definition, no one who seeks asylum can actually be illegal, so the irony of an Illegal Migration Bill being inaccurate in name as well as illegal in substance is… well, it would be funny if the situation wasn’t so dire.

The problem is that, unless you are from Afghanistan, Hong Kong or Ukraine, there are currently no safe, official routes into the UK. In fact, the bureaucratic provision for Afghans is so poor that only 22 people have been resettled via the “official” process as of February 2023 – a stark contrast with the 8,633 Afghans who entered our country via small boats last year.

Like Patel, Braverman herself is the child of migrants, and for many, it’s the fact that she espouses the “crabs in a bucket” mentality that adds insult to injury; the idea that it was fine for her own parents to seek a better life, but we’ve had quite enough of that now, thank you very much.

At the end of Matar, we are reminded of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 14:

Everyone has a right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.

The word that burned itself into my mind was “enjoy.” Should Matar’s “enjoyment” in life be relegated to the occasional moment of camaraderie with other delivery drivers, eating the cast-offs of some rich person?

Our broken system provides no enjoyment, no rights to anything that amounts to more than merely existing. Once in the country, denied the right to work and with no agency to improve their substandard living conditions, refugees are often made to feel that they should only ever be grateful for the crumbs they are given.

The degrading nature of constant, obligatory gratitude is the principal theme of Dina Nayeri’s book, The Ungrateful Refugee: she asks, do refugees not also deserve the luxury of choice? To be able to choose and buy their own food and clothing rather than waiting for scraps for which they must be forever indebted? A system that does not allow refugees to work, while waiting years for processing as the Home Office wades through a backlog of applications, is not a system that cares about efficiency, let alone about the welfare of its candidates.

Hassan received a lot of praise following his involvement in the Led by Donkeys campaign, with commenders pointing to his various achievements, notably his role in pressuring the government to U-turn on its decision to exclude low-paid workers such as cleaners from a policy allowing the family members of NHS workers to remain in the country if they were to die from coronavirus. He’s also a BAFTA-winning filmmaker – casual. However, Hassan is keen to deflect attention from his achievements, in order to avoid the superhero phenomenon that shrouds most refugee narratives in our mainstream media.

There’s work to be done – and it’s bigger than any one individual. Hassan is tireless in his signposting to the incredible work of the organisations he works closely with, such as Choose Love and the Bike Project, both of whom supported Matar. The Bike Project – which provides bikes to refugees awaiting processing, and who provided Hassan with his own bike many years ago when he first claimed asylum in the UK – donated the bike that carries Matar from scene to scene.

In recent years, Hassan has focused a lot of his attention on critique of the government, expressing fears that the UK is moving towards an authoritarian state not so dissimilar to the one he fled years ago. Pointing to the culture wars as an example of deflection, Hassan insists that we must not lose focus (indeed, according to Novara Media, in March this year, Britain spent more time talking about Gary Lineker himself rather than the dangers of the actual policy he was suspended for criticising).

Sadly, Hassan’s desire to hold the British state accountable often leads people to ask him why he “bothered coming to the country” if he takes such issue with its government. In stark contrast to Braverman, Hassan is steadfast in his resolution to make things easier for migrants and asylum seekers who come after him. Although he now has British citizenship, his belonging is still constantly questioned. His reply to the haters?

“Please stop asking me why I came here. I’m here for the lols.”

On that note, and because I am a firm believer in the idea of joyful advocacy, and that joy is a form of resistance, I ask Hassan what he does to feed his soul. His great love is his friends, his chosen family, he says – or, as he calls them, “The Babe Republic.” Whether it’s through getting out of London, going for walks or sharing meals, the Babes keep him going.

Finally, I ask Hassan how he copes with the feelings of regret that he cannot help every asylum seeker or refugee. For him, it’s about holding onto small wins. “If just five people change their mind after seeing my film or through my work, then that’s a great impact,” he smiles. Of course, if those five people then feel inspired to go and vote for politicians who can help effect change that makes life a little safer, a little more humane, and – dare I say – a little more enjoyable for refugees and asylum seekers in our country, then so much the better.

Because everybody deserves to have their own Babe Republic.

What can you do?

- Refugee Action has put together a fantastic list of ways to support Refugees.

- You can watch Matar for free via the WaterBear platform – don’t forget to share with others!

Books:

- Hope not Fear by Hassan Akkad

- The Good Immigrant by Nikesh Shukla

- Border Nation by Leah Cowan

- Migrant, Refugee, Smuggler, Saviour by Peter Tinti and Tuesday Reitano

Articles: