During a recent visit to the University of Ibadan (U.I), the first university in Nigeria, I pondered what attending such an institution would have been like. The response I received was a cautionary one; “you better not even wonder, and thank God you didn’t,” a friend said.

This sentiment aligns with stories I’ve heard about life at Nigerian universities. Overcrowded lecture halls, outdated facilities, inadequate housing and limited access to resources are common issues for students. Additionally, frequent strikes disrupt their academic calendars, leaving students in limbo.

The term “Coconut Head Generation” was first used as an insult aimed at Nigerian youth to label them as lazy and apathetic, but it has evolved into an ironic self-identifier. In his latest film, Coconut Head Generation (Coconut), Alain Kassanda, a filmmaker born in Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and raised in France, explores students’ lives, thoughts and emotions at U.I.

Coconut reveals that despite the difficulties students face in Nigerian universities, some students are actively creating opportunities for knowledge production, raising consciousness, and engaging with political thought on various matters that impact their lives.

Thursday Film Series: An Open Movement

In Coconut, Alain focuses on members of a film club at U.I, Thursday Film Series (TFS), which has become a safe space to screen works and have spirited debates centred around various political topics, including ethnicity, colonialism, and feminism.

Following a recent screening at the Open City Documentary Festival in London, I got the chance to catch up with Alain and Oluwafunmilayo, a former member of TFS, to talk about the film club and the film.

Alain’s four-year stay in Ibadan was inspired by his partner’s research position at the Institute of French Research in Africa (IFRA) with affiliation at U.I. During his time there, he connected with like-minded individuals, including lecturers and students, who jointly established TFS.

Alain says TFS quickly transcended being just a club – it became “a movement.” He describes it as a “safe space” where people with shared values gather to express themselves freely, and which galvanises people with political and social commitments.

Oluwafunmilayo emphasises the vital role played by the collaboration between the Institute of African Studies (ISA) and the African Studies Student Association (ASSA) in maintaining a safe space like TFS amid the oppressive university environment. Specifically, she highlights the Institute’s decision to designate Drapers Hall as a lecture-free venue for the film club’s use. Without this support, “perhaps we would have been forced to relocate under the Coconut tree or something like that,” she jokes.

Recognising the prevalence of sexism, homophobia and other forms of social violence at U.I and surrounding areas, they wanted to establish a space where people who carry these opinions cannot go unchallenged.

Alain mentions, “You couldn’t say anything discriminatory without being checked at some point, because you’d be attacking the very people our club was made up of. And that’s valuable. It goes beyond the cinema, because through the space we’ve created we’ve been able to create a small social movement.”

The draw of TFS lies in its inclusivity. It welcomes individuals beyond the university. While students make up a significant portion of TFS attendees, it also attracts non-students – like Oluwafunmilayo, who joined during her youth service in Ibadan. “The film club opened itself up to everyone,” Oluwafunmilayo says. “The beauty of the film club is that even in such a restrictive and repressive space, there existed a safe space enough that people could come and express all of their angst with the university, the state, in itself, and with Nigeria as a country.”

Oluwafunmilayo’s first experience at TFS was during a screening of Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It in 2019. The engagement in psychoanalysing the film’s characters solidified her commitment to the club, regardless of her non-student status. “In that moment, I knew that I was stuck here,” she says, “and I knew I was going to continue to come.” According to Alain and Oluwafunmilayo, because the club opened itself to everyone, it fostered cross-generational and diverse conversations, leading to valuable learning experiences.

Embracing Difference

Coconut shows TFS as a space marked by open and robust conversations, reflecting diverse opinions and often igniting passionate and heated disagreements. This atmosphere underscores the necessity of embracing differences in thought and opinion.

This act reminded me of my engagement with Black feminist love-politics as elaborated by thinkers like Audre Lorde and Jennifer Nash. This practice of love aims at healing, change, and liberation by embracing everyone, tying us to a diverse range of experiences and traditions.

To embrace Black feminist love-politics is to revolutionise our understanding of the public sphere as a space open to all for critical engagement with each other’s differences.

In Sister Outsider, Audre Lorde writes: “I urge each one of us here to reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside herself and touch that terror and loathing of any difference that lives there. See whose face it wears. Then the personal as the political can begin to illuminate all our choices.” By recognising and dismantling this fear of difference, we pave the way for meaningful change.

Toppling the fear of difference involves acknowledging, embracing, and actively engaging with these differences. I should emphasise that this isn’t about allowing oppressive and bigoted differences in opinion to go unchallenged, but it’s also not about suppressing or penalising them either – rather, it’s about striving to understand them. This recognition enables us to address the issues arising from these differences with empathy and insight, while respecting their historical contingencies in people’s lives.

This approach fosters a communal sentiment characterised by deep caring and respect for every individual, grounded in secure self-love. Admittedly, this is an act that I am still learning.

Therefore, differences are not shunned but welcomed in spaces like TFS, even when they lead to heated debates. As it’s within these debates that education, learning, growth and a deeper understanding of each other occur.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

As Oluwafunmilayo tells me, “We had some days that everybody was so heated that we had to end.” But this was no bad thing. These days are pivotal for the movement because they enable us to express our perspectives openly, hold each other accountable, and pave the way for understanding and growth.

While these discussions might not result in immediate friendships, they facilitate a deeper comprehension of each other, promote consciousness-raising, and foster community building. I genuinely believe that in the pursuit of the future we envision, it’s vital that we maintain the freedom and openness to express our views and address our shortcomings collectively.

#EndSARS did not happen in a vacuum

The film transitions from the TFS to the height of the #EndSARS movement in Nigeria. #EndSARS garnered global attention as a response to police brutality, specifically in the hands of Nigeria’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS). Evolving from this outrage, Nigerian youth and activists harnessed social media and staged peaceful protests, demanding accountability, an end to police violence, and transparent governance.

On 20th October 2020, the Lekki tollgate massacre marked a tragic turning point when security forces allegedly fired upon unarmed peaceful demonstrators, resulting in multiple casualties, as captured on social media.

While Coconut includes footage from the #EndSARS protests and afterwards, what’s particularly intriguing is that some footage of discussions predates these particular protests. Before the #EndSARS movement, the students discussed broader systemic inequalities, power imbalances, and lack of accountability across various sectors, demonstrating that police brutality was just the tip of the iceberg.

One critical issue discussed in the film was an incident that happened at the university where a Student Union president was suspended for confronting the university about the lack of provision of student IDs. This often led to harassment from the police, who took advantage of this to extort students. We see the suspended student sharing this encounter with us and other students. This scene was shot before the #EndSARS protests.

For Alain, this reveals that “all the grievances and demands that were made during EndSARS were already being discussed in the society well before, so it wasn’t out of the blue.” It becomes clear that the #EndSARS movement didn’t materialise out of thin air; it was a culmination of years of accumulated issues and frustration towards police brutality and lack of action to protect the youth.

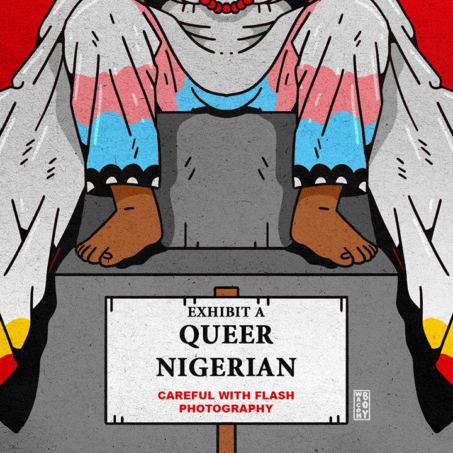

Coconut also served as a reflection of our actions during the #EndSARS movement. We watch footage from TFS after the #EndSARS protests, where the students discuss how our actions illustrated the lack of intersectionality in our struggles. Queer people were unfairly targeted and accused of attempting to hijack the movement because they drew attention to the specific ways they are affected by police brutality and complex power dynamics in Nigeria. These showed the need for a more comprehensive approach to our liberation movements.

Negotiating visibility

One thing we can universally acknowledge is Coconut’s remarkable role in archiving and storytelling, as well as its potential for raising awareness. This holds particular significance in Nigeria because these perspectives of the youth are not mainstream.

The movie has received recognition in cities like London, Paris, and New York, resonating with themes like police brutality, housing issues, homelessness, power imbalances, and discrimination.

The screening in Paris coincided with French President Macron’s pension reform, marked by demonstrations met with violence. At the Paris screening, Oluwafunmilayo was deeply moved: “It’s such an important thing that just being the fullest expression of ourselves in our humanness is something that others can find themselves in,” she says. Alain additionally highlights how the film “operates as a mirror” for Western audiences to relate to African struggles on equal terms, challenging notions of superiority.

However, I noticed there had been no screenings in Nigeria during my research, prompting me to inquire about Alain’s plans for dissemination in Nigeria. Alain points out that the discussed issues remain sensitive, with individuals allegedly involved in the violence during the #EndSARS protests currently in power, evading justice.

This situation raises questions about the public screening’s impact on TFS and its visibility. Alain ponders: “how do we make sure that we have a public screening in Nigeria without putting those in the film and the whole structure at risk?”

As Alain points out, “one of the reasons why TFS has been able to operate is because it is under the radar.” The dissemination of this film in Nigeria reveals the extent to which the university and the structures are critiqued, and places a target on the back of TFS in ways that could affect their activities.

This dilemma leads to a broader question about archiving and disseminating materials related to marginalised groups. I am seriously considering this in my research on queer activism in Nigeria. It is a complex challenge to balance the importance of making such content known with the potential harm it could cause. We must be cautious about disseminating materials that expose vulnerable individuals to negative visibility.

As I write this article, I am deeply troubled by the complexity of recognising the importance of people knowing this film exists, while simultaneously being cognisant of the implications, and how this article, which is publicly accessible, contributes to the implications. I have never been more aware of the ambivalence of our existences as we fight for justice as I am right now.

While we recognise the film’s significance, we must also consider the potential consequences for TFS and its members, and the negative implications of these discussions.

Our conversation didn’t yield a definitive solution, but it emphasised the need to balance dissemination and security. Alain intends to address this concern when he visits Nigeria soon. The paramount issue for Alain is not just getting the film seen; it’s about ensuring it’s done right and the people involved are kept safe.

What can you do?

- Watch the Coconut Head Generation Trailer

- Watch the interview on Coconut Head Generation with Alain and Abayomi

- Read Practicing Love: Black Feminism, Love-Politics, and Post-Intersectionality by Jennifer Nash

- Read Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde

- Watch Journey of an African Colony on Youtube

- Read more articles by Adebayo: