Something transformative is happening at the Museum of Transology (MoT). Its rapidly expanding collection of protest placards is helping to fuel the burgeoning trans rights movement. The Archiving Lates events, where volunteers catalogue donations, is nurturing London’s trans community. This allows it to work as what sociologist Stuart Hall calls a “living archive,” operating in a circular way that goes beyond the traditional, conservative practices of archiving.

These days, trans street protests happen almost weekly. But until very recently, as explored in Trans Britain, edited by Christine Burns, trans activism was a closeted practice, made up of ‘friends in high places’ educating the public and pushing for legislative change.

By 2008, the UK’s largest trans rights protest only numbered 150 people. Five years after this, the UK’s first Trans Pride welcomed 1,500 people in Brighton. Less than a decade later, over 20,000 people marched in London, and many more across the country.

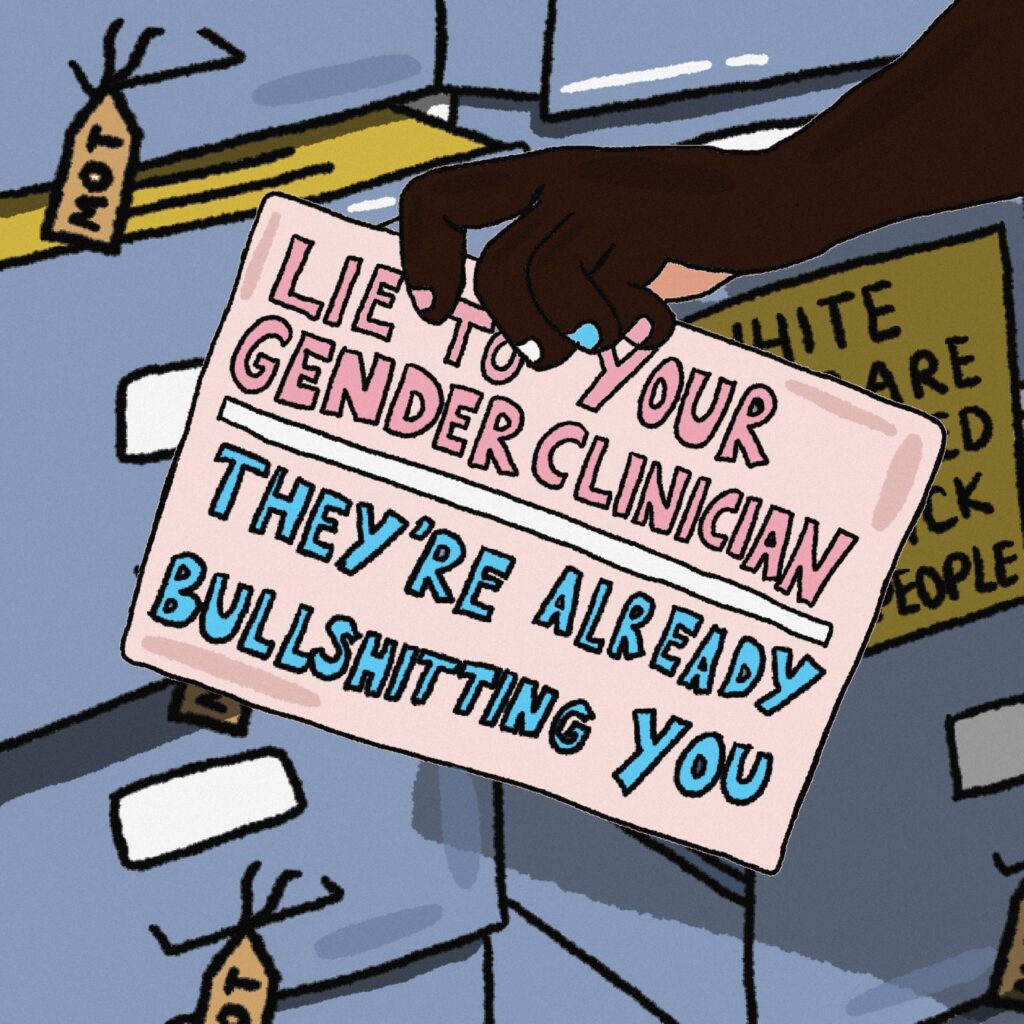

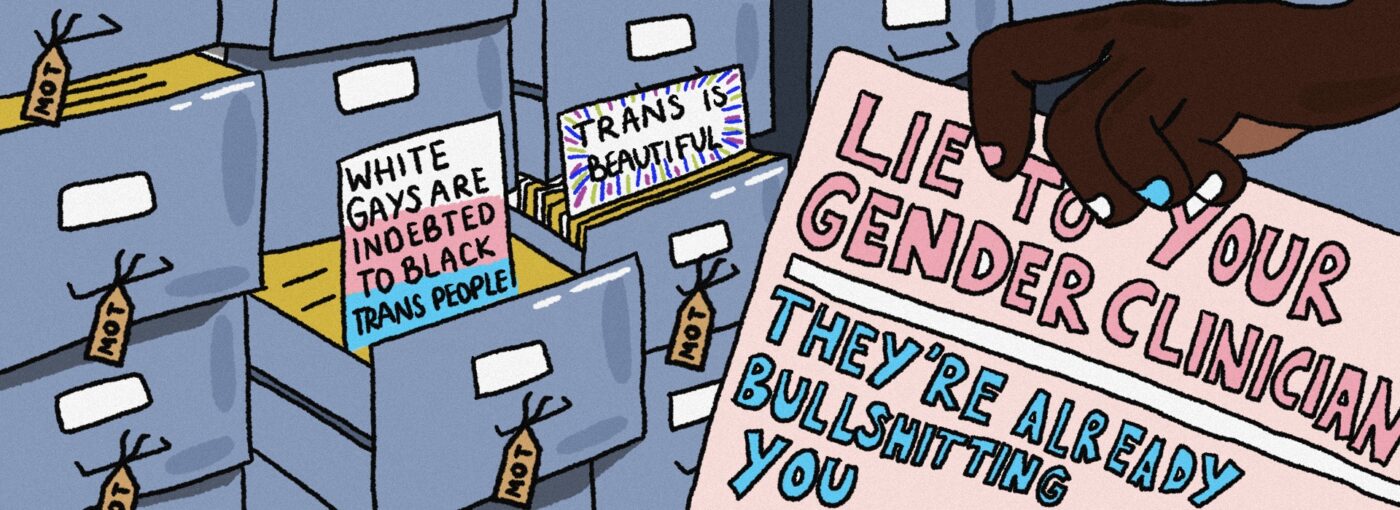

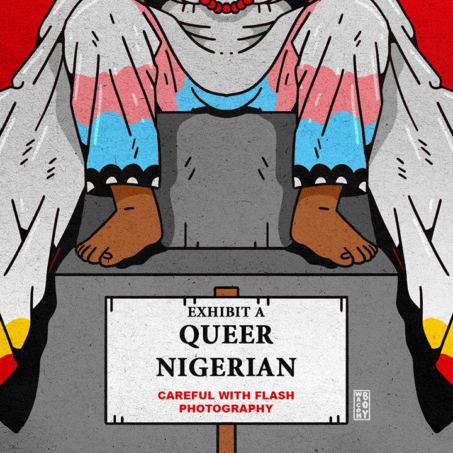

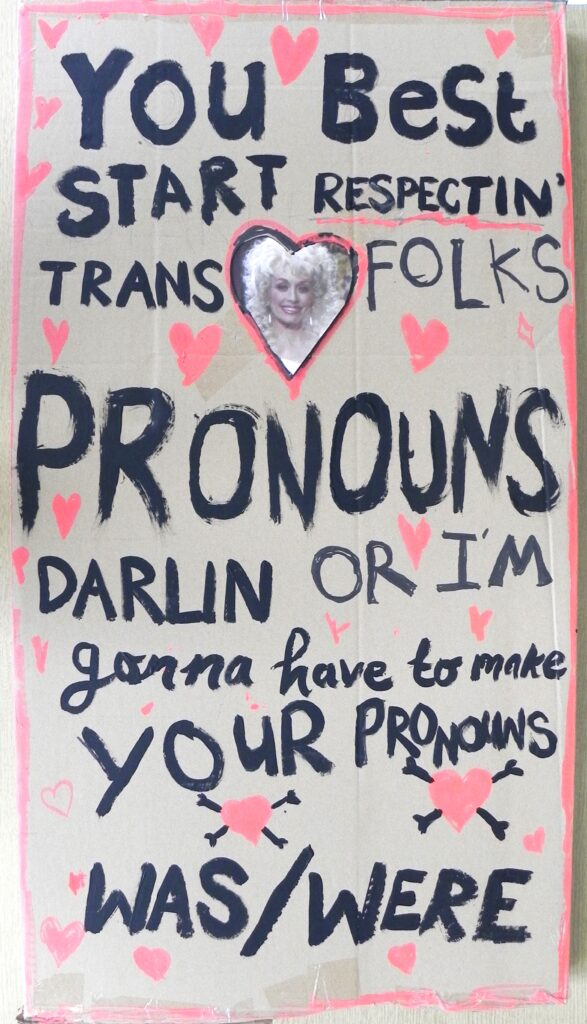

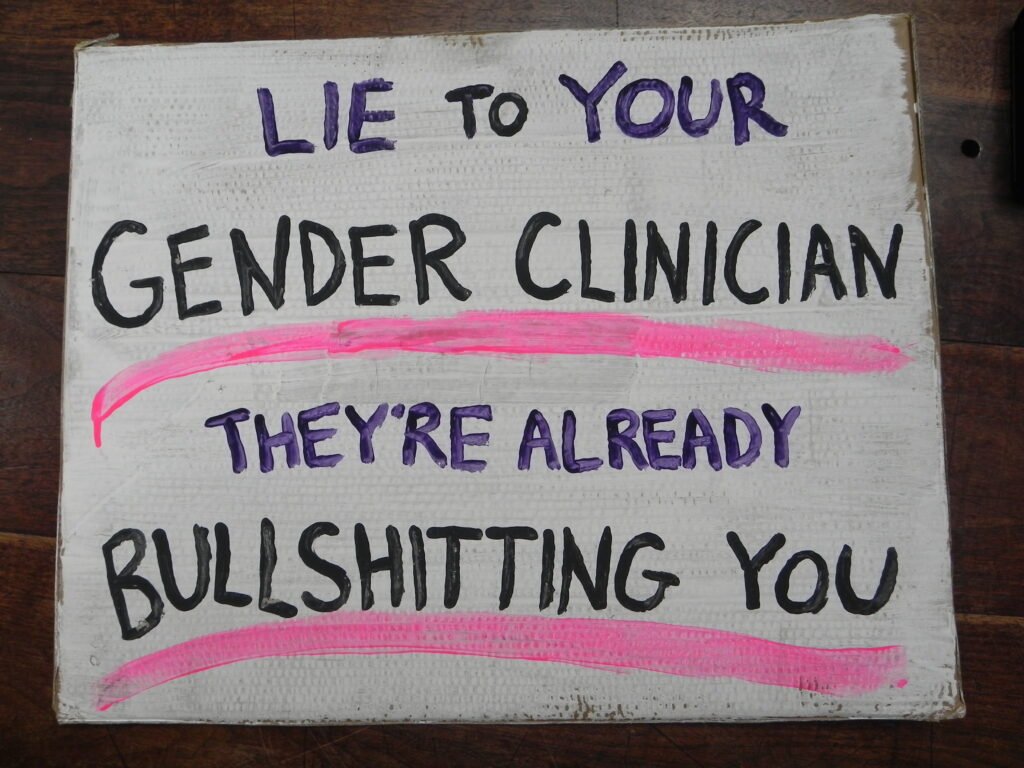

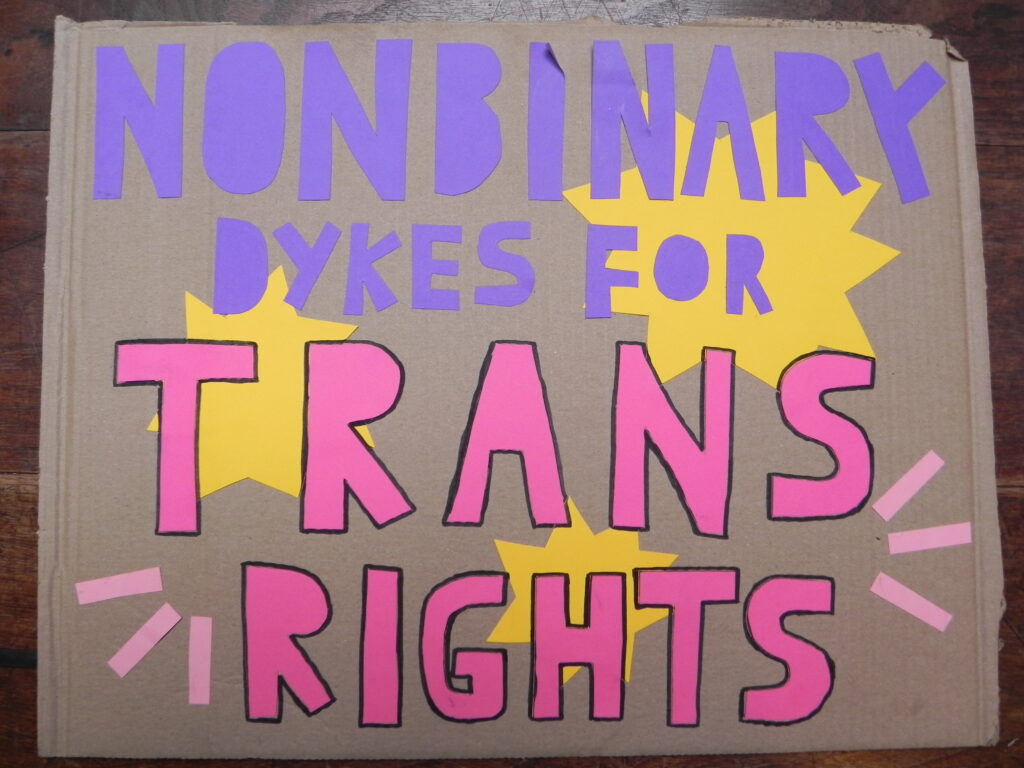

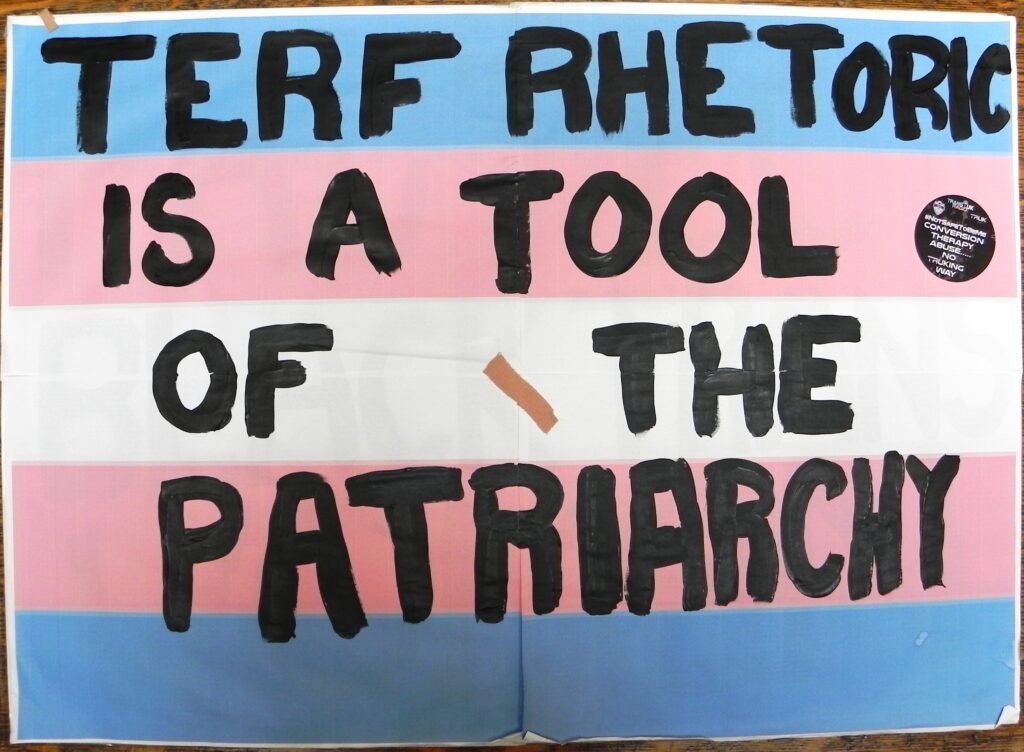

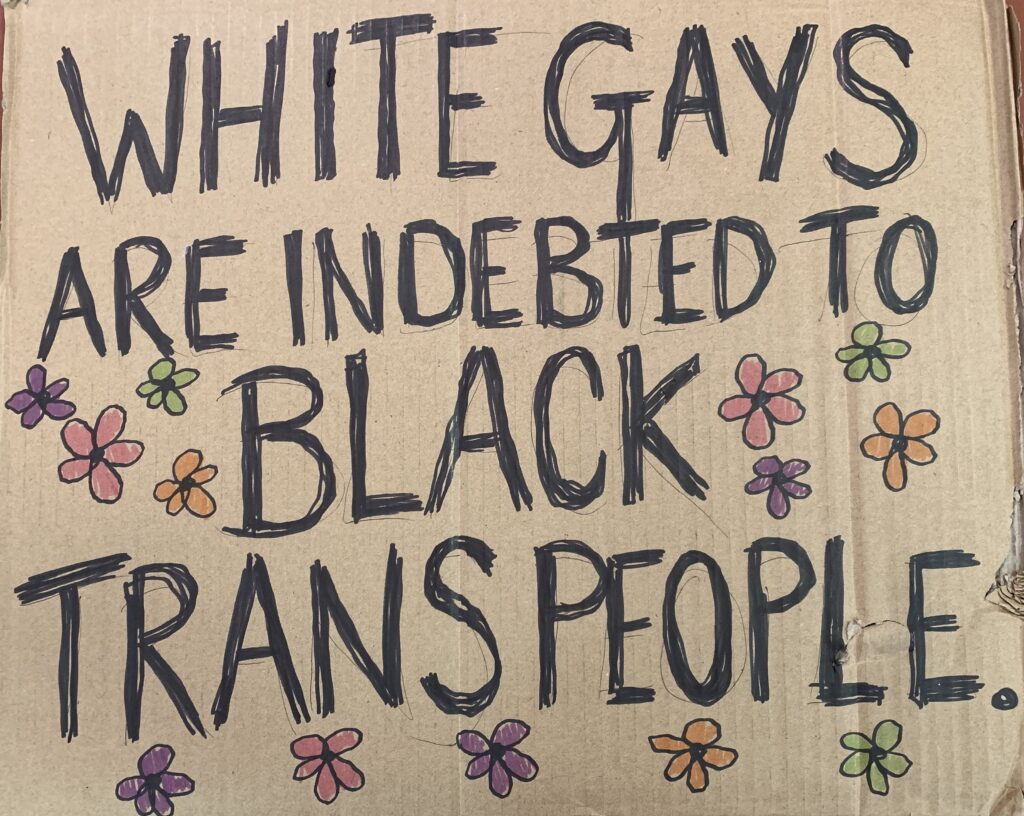

The MoT’s protest placard collection exists to record this meteoric growth. Placards were first collected from Black Trans Lives Matter in London, part of a commitment for “white curatorial labour to make queer museums anti-racist.” Intended as “the founding objects of the Museum of Transology’s QTIBIPOC collection,” the initiative proved so successful it was quickly expanded to form its own collection.

The ever-growing placard collection is a new way of working for the museum. Before, it received donations of everyday objects: someone’s first binder, a break-up letter, an empty packet of binding tape. Eventually, this felt like too little, too late. MoT founder E-J Scott says so themself: “We couldn’t wait anymore for people to send us their stuff… there were events that we had to cover.”

Now, the museum goes out to gather objects in a collection that is, in Stuart Hall’s words, “on-going, unfinished, open-ended.” This living archive has a unique relationship to time. It is no longer the traditional prison-house of the past, collecting yesterday’s objects so we can reflect on them tomorrow, from a safe distance. Instead, it actively shapes this tomorrow by cultivating trans life today.

Where other archives collect objects from a past they might be unable to affect, the Museum of Transology works to produce the very reality that it records. It actively promotes the protests that it collects from, and organises “Know Rights” workshops to protect trans protestors. This circular practice shatters the traditional archiving method that was established by the collections of legal, colonial, and carceral institutions. And the circle runs wider and more inclusive than just a simple donations policy.

Each month, as many as 80 volunteers descend on the Bishopsgate Institute for Archiving Lates events. Here, the museum opens the doors of its cataloguing process. Most of us are trans, all of us down for liberation, and none of us formally trained in archival work. We sift through piles of placards, fill out cataloguing forms with their details, and build new piles. It’s not glamorous work, but this is where the archive’s true community building work happens.

E-J is clear that the purpose of these events stretches beyond pure archival preservation: “It’s about us being together in a calm, quiet space, with objects from our community.” We work together in the old wood-panelled library of the Institute, and the magic happens alongside.

At these events, the Museum does something more than fuel a growing political movement. It nurtures the community at the heart of this movement, producing opportunities for us to meet, and share in our resistance. Some of us make new friends and form collaborative partnerships. Some learn about careers in the history and archives sector. Some grieve the recent loss of a friend.

When artist Topher Campbell set up Rukus!, Britain’s foremost Black LGBT archive, he described it as “a very personal endeavour.” We feel this at the Archiving Late events. Here, we hold and care for objects that resist the violence of transphobia, at the same time as our own, queer lives. Sometimes, you come across your own placard, staring back at you in the pile, and feel the circle of history closing around you. Not with the usual violence of erasure. But as an open invitation to step into the fold.

There is one weak link in the chain: the accessibility of donated materials. Placards are currently held at the Bishopsgate Institute, accessible in theory to anyone interested. However, the Institute is little known outside of queer history circles and its online catalogue is dreadfully hard to navigate. The Museum of Transology’s own website is more engaging, but the placard collection is totally absent from it. The dream would be a fully digitised collection, but this takes money, and time not spent on other important things.

Until then, the best way to engage with the Museum of Transology’s archive remains as a participant. Archiving Late events are open to anyone with an interest. The work is simple and the training is good. It’s an opportunity to connect with trans history. Not as a long-gone past that you can consume to affirm your present. But as a collective effort, a creative process around which to gather and meet with others, to nurture our lives today, and secure our lives tomorrow. As E-J Scott says so himself: “collecting is connecting.”

What can you do?

- Attend an Archiving Lates event at the Bishopsgate Institute

- Collect and donate your own Trans artefacts to the Museum of Transology

- Follow the Museum of Transology on IG HERE

- Read The Transgender Issue by Shon Faye

- Read A Working Class Family Ages Badly by Juno Roche

- Support trans artists working with archival materials:

- Read more articles on shado:

All placards courtesy of The Museum of Transology @museumoftransology