When Nigerian artist and photographer Aisha Seriki was a young child, she encountered the sharp end of the UK’s border system as she and her family moved from South East Asia to eventually reside in London. Her experience at The Home Office, a police state system which continues to impact her life through denying her father entry to the UK, has necessarily shaped her perception of the world. Years later, she’s creating work which speaks to the experience of migrants in the UK while fighting back against these same systems which continue to unfairly target and oppress Black folks and people of colour.

Inspired by her father’s obsession with photography and the actions of Black historical figures such as Josephine Baker and writers like bell hooks, Aisha opens up the art world to those who have been purposely excluded throughout history. By producing new images of Blackness which speak to real experiences, she also aims to break apart the colonial monolith which makes up the vast representation of Blackness. We caught up with her to find out more.

What are some of your biggest influences and motivations in your work? What issues are you passionate about working on?

I would say that one of the biggest motivations behind creating my work is that I want to make work that speaks to my younger self, who did not see herself represented in mainstream art and media. I think that there is something powerful about feeling seen and I hope that Black women and women of colour can see a piece of themselves in my work.

I would actually say that my work is mainly influenced by the writings of Black activists. I regularly reference the philosophies of Steve Biko, Franz Fanon and Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Most recently I have actually been reading a lot of bell hooks which directly feeds into my work, as I am really passionate about visual presentations of Black womanhood.

My life experiences are also massive inspirations behind my work. For me, this is important as by imbuing my art with my own experiences I’m helping shape what is known as Black art.

The effects of colonialism mean that Blackness is often seen as a monolith, something which disregards the intersectionalities and diversity within the Black experience. I hope to challenge these perceptions by showcasing my life experiences as a way of diversifying the understanding of the Black identity.

How has your lived experience shaped your practice?

Personally, I see the personal as political, so I cannot separate my experiences from wider social issues. My experiences of dealing with The Home Office made me self-aware of my position as a Black Nigerian female migrant from a very early age. Later in my teenage years, I was able to connect the dots and start thinking about my experiences not in isolation, but rather as part of larger systems which unfairly discriminate against Black people and people of colour.

Photography is then the medium which I utilise to showcase and bring awareness to social and political issues affecting Black people in the present day.

Can you tell us a bit more about your recent ‘Heaven is not closed’ project?

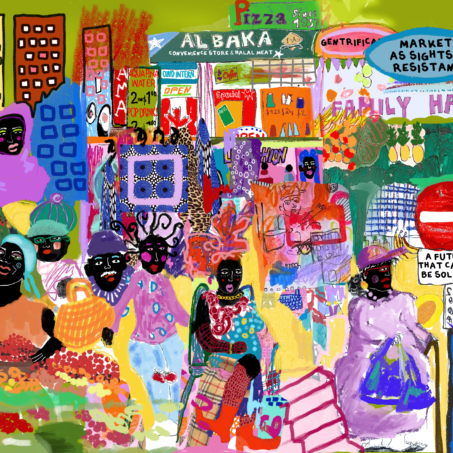

‘Heaven is not closed’ was created as part of my final piece for the Night School programme, a free eight week training course by Yellowzine and The Brooklyn Brothers. The project was inspired by a trip to Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Although the paintings were outstanding and undeniably beautiful; the clear absence of Black people in the gallery was hard to ignore.

For centuries, museums and galleries have been regarded as the hallmark of culture. But even though museums have been a hotspot for representing cultures and experiences all over the world, they have always underrepresented Black women. This is despite the contributions that Black women have made and continued to make to Western society.

Because of this, I wanted to create a powerful project that depicted Black women in a similar manner as the portraits in the Uffizi. The women showcased in my work are not professional models – a deliberate choice to further highlight the point that everyone should be visible in these spaces. The centrepiece of the project is the three girls linked with each other, to highlight unity and also community. By using the museum as a backdrop for my project, I aim to show that the art world is not closed to us.

What role do you see your work in challenging or celebrating representations of women?

Throughout history, Black women have been subject to various racist tropes which have been projected onto us through the media, literature and society. I often reference Black women who have challenged these stereotypes in my work.

One of the bodies I have been working on is inspired by the French-American dancer and musician Josephine Baker who used her talents as a way to combat racial injustice. Josephine is most known for her work as a dancer, especially her infamous performance of the Banana dance in Paris in 1927. This dance subverted western perceptions of Black femininity. Aware of her sexuality and femininity, she used her body as a site of political resistance to challenge her audience’s fetishisation of non white bodies, showcasing the Black female body as beautiful. Josephine was seen as both the face of ‘primitivity’ and the new modern form of femininity. Josephine’s animalistic dances were used as a way to question western fetishisation of black femininity and the colonial gaze.

Using her fame and success as a cover, Josephine also worked as spy for the French resistance contributing in war efforts against the Nazis. The impacts of Josephine’s legacy can still be felt today and she continues to be a reference point for many women across the world.

Just like Josephine, I also aim to create work that questions the politics of beauty, which I believe cannot be separated from colonialism and euro-centric beauty standards. I want to celebrate and showcase representations of Black women who do not fit within this standard.

Where are you based and what excites you about the creative community around you?

I am currently based in South London. I feel really lucky because almost everyone I meet is either a full-time creative or working on a creative endeavour.

For the past two years I’ve been working full time, so I’ve found it hard to really engage in creative events apart from my own. But I have just started my Master’s in Photography and I have already met loads of great people. I would say that the thing that excites me about the creative community around me is that everyone seems really determined to create and become better.

I have had the opportunity to see my friends and family begin and continue to develop their creative practice over the past few years. It is really inspiring to see and I honestly can’t wait to see where all the hard work will take them!

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

You discuss the absence of Black artists and subjects in art museums and galleries. Can you speak a little on the importance of decolonising through representation in these spaces?

Art institutions should reflect our realities and existence, so we must democratise and decolonise art institutions at every level. Various voices and experiences must be accounted for, and it mustn’t be just the same stories which are constantly re-told.

I also believe that representation also plays a big role in this process. However, institutions mustn’t engage with representation as a way of just fulfilling a quota. It is critical that curators do not engage in the works of minority artists superficially and pigeonhole their works into a box that does not exist outside the limits of diversity. If not undertaken in this way, representation just reinforces the other-isation of minority artists, making them something that exists outside the main art canon.

I also think it is vital to make a distinction of what kind of representation is needed. I believe true artistic representation is when an artist creates imagery or works that are counter-hegemonic and resist white supremacy by producing new and different images of Blackness to account for the diversity in our lived experiences.

You talk about the influence of Black activists in your work – how have you seen the movement evolve in the last few years and what is exciting you about it at the moment?

I do think that we are at a special time when it comes to the movement. I think the most recent Black Lives Matter movement made an impact by providing visibility to the works of Black activists, artists and academics exposing their works to larger audiences.

I am also happy to see that some of my favourite artists, activists and writers are finally getting the recognition that they deserve. It has been really interesting to see conversations about race propping up in the mainstream in a way that it has never been before.

There have been obvious limitations – I remember at a certain point it felt as though brands and institutions were using the protests as a sort of marketing ploy to prove that they were not racist. So, I think it is going to be interesting to see how many of those brands and institutions will actually keep their promises and provide opportunities for Black people in the long term. I think we are still yet to see the full impact of Black Lives Matter and I am excited to see what that will be.

Can you talk a bit more about the impacts of The Home Office and hostile environment communities around you and why visual storytelling is so important in amplifying this?

I feel like the impacts of The Home Office cannot be quantified. Anyone who has an experience with The Home Office or knows someone who has an experience with The Home Office can testify to this.

Even when your documents are finally sorted out, or you get citizenship I feel like the paranoia never fades away. If I have to sum up my experience I would say that it feels like you are constantly walking on eggshells and this can have devastating impacts for your mental health.

I believe that visual storytelling has an important role in highlighting the impacts of the hostile environment. I feel like migration is typically discussed in terms of the macro in mainstream media. It can almost feel like we are talking about numbers and not the daily lived experiences of people. So, I think visual storytelling is an important tool to combat this by bringing awareness to the impacts of the immigration system on individual lives.

What are you currently working on?

I am currently working on a project that explores how migration affects conventional and societal expectations of love, specifically analysing how family ties have been restricted by arbitrary borders.

This series is inspired by my own experience of separation from my Dad, who has been barred from this country for over 15 years due to constant rejections from The Home Office. The project aims to shed light on the emotional costs of immigrating which are often neglected in discussions of migration.

The project I was working on was recently part of an exhibition called “Becoming British,” and the majority of the people who visited the exhibit were shocked to hear about the experiences some of the artists had with The Home Office.

I think most of the information in the media about migrants involves fear-mongering and as a result, a lot of people do not know the types of hurdles we face to live in this country. I believe that it is through exhibitions like “Becoming British” and visual works by migrant artists that we can start to uncover the realities of migrants in this country.

What can you do?

Read any and all of the below:

- bell hooks: “Art on my Mind” Visual Politics

- bell hooks: Black Looks Race and Representation

- bell hooks: Salvation : Black People and Love

- Ngugi Wa Thiong’o: Decolonise the mind

- Ngugi Wa Thiong’o: Devil on the cross

- Franz Fanon: The Wretched of the Earth

- Mark Sealy: Decolonising the Camera: Photography in Racial Time

- Steve Biko: I Write What I Like

Listen to these podcasts:

Watch:

- Daughters of the Dust by Julie Dash

Follow:

All photographs courtesy and under the copyright of Aisha Seriki

All photographs courtesy and under the copyright of Aisha Seriki