The international community seems to suffer from short-term memory loss. Few seem to remember that during the 70s and 80s, the United States put into motion a plan to politically control what they always considered their ‘backyard’: Latin America. A plan which involved multiple political coups, violence and the establishment of neoliberal economic policies, all with the help of the US government and the CIA. I am sure you are wondering how this is related to climate change and the incoming Biden administration. In this article I will try to navigate our way towards that answer.

A splash of history

The Condor Plan, also known as ‘Operation Condor’, was the coordination of actions and mutual support established in 1975 by the leaders of the dictatorial regimes of South America with the US. This plan was central to the US’ Cold War strategy. Guided by the National Security Doctrine, the US fostered dictatorships in Latin America in order to suppress left-wing political sectors and to promote new economic models. This guaranteed benefits to conservative sectors and secured the US cheap access to the region’s natural resources.

This strategy involved the surveillance, interrogation, rape and murder of people considered by these regimes as subversive. It also included the imposition of a neoliberal economic regime, first tested in Chile during the Pinochet dictatorship with the help of the famous ‘Chicago Boys’. The Chicago Boys were a group of Chilean economists, recruited by professors from the Chicago University during the 70s, that were later trained in the Department of Economics of said University, following the liberal ideas of Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger. They embedded this US-learned economic regime which was later replicated throughout the region. This economic model was based mainly on the deployment of highly extractivist industries in combination with the progressive elimination of national industries. During this 20 year period, Latin America’s economy was re-primarised and engineered to become a warehouse of resources that companies in developed countries could access at a very low cost.

Flash forward 35 years and this model imposed by the US and other Global North countries, although increasingly resisted by local populations and some governments, continues to dominate the narrative in the region. This is why, we here down south, are curious and somewhat wary of the plans the new Biden administration has for our region.

Echoes of the North

On 20th December 2020, Biden promised that during his presidency he would put the US “on the path to creating a carbon-free electricity sector by 2035”. He also promised a 100% clean energy economy with the aim of reaching net-zero emissions no later than 2050. Here is where the tension with our region comes in. If Biden is to deliver on his promise, the demand for metals like copper and lithium (key materials for the infrastructure needed for the generation of renewable energy) will clearly increase. Let’s take a guess on where the US could get those metals from. If you are thinking what I’m thinking, then yes, Latin America is set to be his biggest provider.

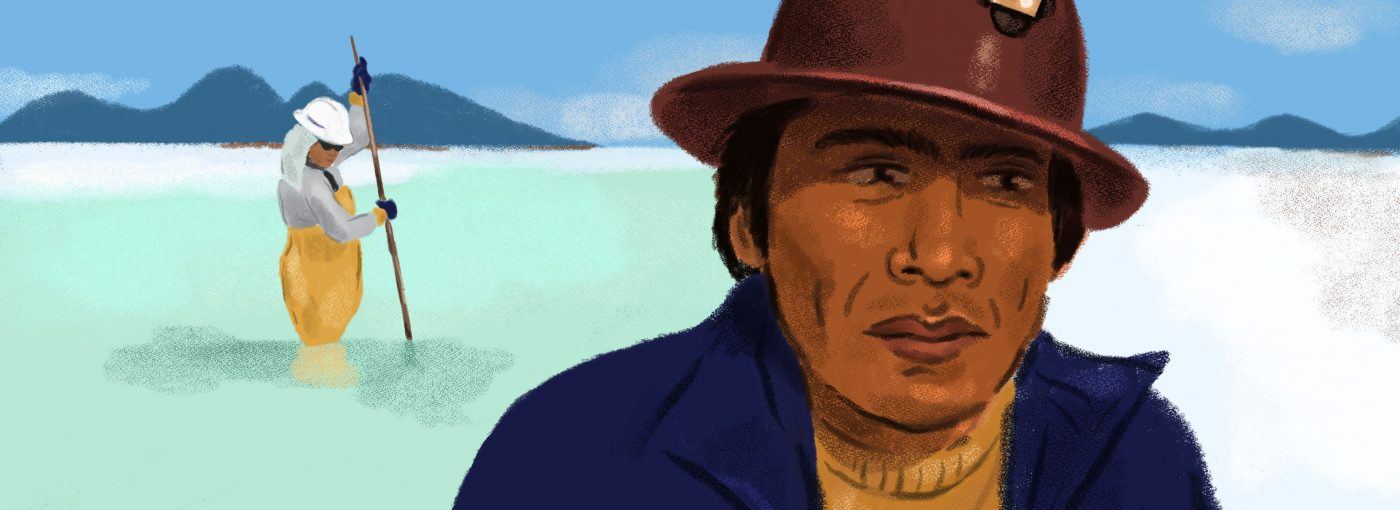

These energy reconversion policies will make the extraction of natural resources from Latin America one of the primary objectives in the US-LatAm relationship. Let’s take a quick look at the region: Brazil is full of rare earth metals like niobium, which is an alternative to cobalt, a metal used in the manufacture of electric vehicles. In Colombia, there are companies ready to dig for copper, a metal that will be key to the clean energy revolution and the production of electric vehicles, a key element for the US net zero plan. Lastly, Argentina, Bolivia and Chile share the largest lithium reservoir in the world, in the famous ‘lithium triangle’, a geographical area that concentrates more than 85% of the reserves known on the planet. Lithium, in case you didn’t know, is a highly necessary metal for the batteries of electric cars. Jackpot.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not arguing that the technological conversion towards carbon-free electricity or renewable energy is an inherently bad thing. What I do think however, is that in the crisis we are living in today, there is a problem of viewing these options as magical one-size-fits-all solutions to cure our problematic relationship with fossil fuels.

But like COVID-19 vaccines, the benefits and externalities of the energy transition will once again be unequally distributed.

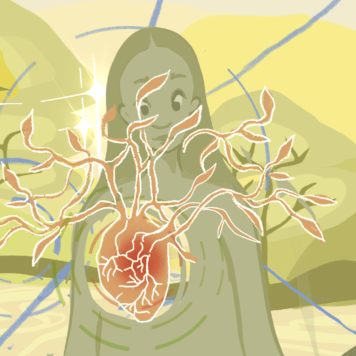

For Global North countries, clean energy, electric cars and clean air awaits. This is at the expense of the Global South, where we instead face open pit mining, the pollution of our rivers, greater inequality and a rise in violence in disputed territories. Sounds fair, right?

Now that environmental issues are storming the narrative, the time has come for us to ask: what is the price of each country’s sustainable development? Some say that the concepts of developed and developing countries are stages of the same path: a country needs to pass through the ‘developing’ stage to later reach the ‘developed’ one. Well, I disagree. ‘Developed’ countries would simply not exist without the exploitation of countries from which they can take cheap resources without regulations. It is no coincidence that, time and again, efforts to promote national industry and development in Global South countries are directly and indirectly suppressed.

It is not by chance, that on the journey of this Global North energy transition, Elon Musk himself (whose company mainly manufactures electric cars) explicitly supported the 2019 coup in Bolivia. The billionaire, in response to statements claiming that the coup had been orchestrated so that the US could obtain Bolivian lithium, said: “We will coup whoever we want. Deal with it”.

Simple solutions to complex problems in a very convoluted world

Whether via extreme billionaires or from new administrations themselves, the US has continually orchestrated the regional agenda in Latin America. This new bet by Biden to hold up American industry with the manufacture of electric vehicles looks to be the latest iteration of this and will be one of the defining points in its relationship with Latin America. To make matters worse, our region is infamous for the archaic regulations that govern environmental practices. It’s also the most dangerous region for environmental defenders, registering approximately 60% of the murders of defenders in the world according to the most recent report by the NGO Global Witness.

Climate change is a global and complex problem. It has no magical solution, no matter how much we may want electric cars and windmills to save the day. We need to understand that, as with COVID-19, unless everyone is safe, none of us are. Climate change knows no borders so, no matter how brilliant the NDC (national climate plan) of a country is, if it is not thought of and implemented with a global vision in mind, it will be useless. We must understand that Latin America is a complex region with many different problems but, above all, it is trapped in a constant state of being trapped in an unequal relationship with the US and Europe. The measures to advance climate action, especially those created by the countries of the Global North, must view the climate crisis through the lens of human rights. If not, we in the Global South will once more be the backyard – or worse, the landfill – of this new chapter in our relationship with the Global North.

See more of Javie Huxley’s work on instagram