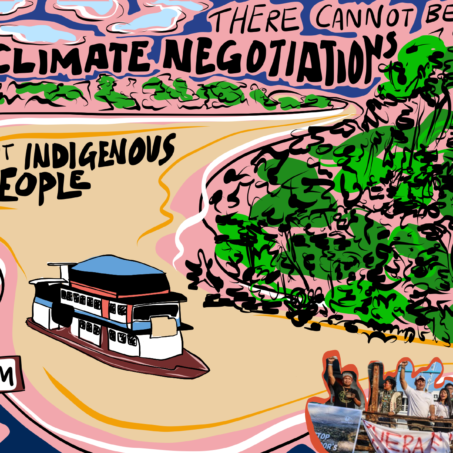

During last year’s Climate Week – an annual event held in New York that brings together global climate leaders from business, government, and civil society to highlight climate action – The New York Times lampooned the gathering, headlining it as having become a “Burning Man for climate geeks.” The article also quoted Oscar Soria, campaign director of Avaaz, as calling it the “Davos of climate…. More exclusionary, more for the elites.”

While these comparisons should have been cause for concern within the climate justice community, responses included a celebration of a profiled environmental activist in attendance and defensive dismissal of the article as divisive clickbait.

However, it is prudent that we consider the potential of there being some truth in these statements – that elitism exists in the climate activism space, and that the transformation of Climate Week since its creation in 2009 is a symptom of what may presently be happening within the climate space at large.

The nature of elitism allegations

Environmental elitism as a critique to the movement isn’t new; it has existed since the emergence of the modern environmental movement in the late 1960s. However, while allegations of elitism are often erroneously conflated and collapsed into a definition centred on economic might and the 1%, they are truly varied in nature.

In 1986, sociologists Denton Morrison and Riley Dunlap outlined three types of elitism that environmental movements are criticised of embodying:

- compositional elitism: supporters of environmentalism are primarily from the privileged or upper socioeconomic class, and environmental concern is higher in upper socio-economic classes;

- ideological elitism: environmental reforms have the underlying purpose of distributing benefits only to environmentalists rather than non-environmentalists and the less privileged;

- impact elitism: whether intentional or not, environmental reforms can “create, exacerbate or sustain social inequities.”

Many examples from the past and present counter the validity of arguments concerning compositional and ideological elitism. For instance, the Flint water crisis contradicts these claims as a key example of working class communities of colour fighting for an outcome that benefits society as a whole. By holding the government accountable for providing unsafe drinking water and successfully winning a settlement that required the city to replace all its lead pipes, the people of Flint improved the lives of environmentalists and non-environmentalists alike. However, of the three elitism accusations, it is impact elitism that I believe is most strongly taking hold in the climate justice movement today.

The threat of elite capture

In our current attention-economy-driven world that places importance on virality and individualism to serve corporate outcomes, individuals don’t necessarily need to have excessive economic means to have outside social influence. As climate action and environmentalism has favourably become trendy, those who have publicly led and inspired climate action have gained significant social and cultural capital via both legacy media and social media.

Public-facing climate activists with a significant social media following occupy a space among the cultural and social elite. This is not to be confused with the political and economic elite (although there may be overlap in some cases). Instead, they hold significant cultural capital, with considerable influence over shaping the nature of climate justice discourse, knowledge production, and societal behaviour. It is in this way that they are elite.

Generally, activists have used their growing fame and social capital from the commendable work they do to help build much needed momentum and support for the cause, financial or otherwise. Unequivocally, gaining this social capital and public attention has also brought to them professional opportunities and access to networks that can help ensure that their material needs are met.

More often than not, engaging in climate activism as a full-time endeavour – the case for many of these activists – often does not put enough food on the table. Funding for climate activism is severely lacking, leading many activists to collaborate with businesses and brands that market sustainable products and services through paid advertising or influencer PR packages containing free samples of products. According to conversations with a few activists who have done such collaborations, some are still not remunerated in line with living wages.

The problem with this dynamic isn’t just that activists are forced to interact with companies to earn enough to make a living, but that it leaves the movement and its vanguards vulnerable to co-optation by the economic elite and capitalist entities; a type of “elite capture” by such entities that see sustainability as something that can be easily accommodated to amass wealth for the few.

According to philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, this elite capture, which is often used to illustrate the hijacking of political projects by the well-positioned and well-resourced,can also be attributed to a system and population-level phenomena that can “explain how public resources such as knowledge, attention, and value become distorted and distributed by power structures.”

He also states that elites, even those from marginalised groups, can benefit from existing power structures in ways that may seem to align with social progress by relying on “fantasies about the exchange rate between the attention economy and the material economy.”

This environmental elite capture currently taking wing inadvertently justifies and allows for a reformed version of the current neoliberal capitalist system – a “green capitalism” that does little to change a structure that many of the same activists decry as the cause for the climate crisis, let alone bridge existing income inequalities and class disparities.

Contextualising elite capture

With sustainability now given the verified “blue tick” by capitalism, luxury brands, the economic elite, and even large companies marketed as sustainable and ethical have increasingly used climate activists and sustainability influencers as a way to amass and justify their growing profits. Via association with climate activists, the product-pushing powers are provided with the social licence to continue operating on flawed capitalist structures – a type of insidious greenwashing, or “social-washing.”

In the past year, a growing number of luxury sustainable companies and sustainable fashion brands have adorned climate activists and influencers with their garb at various award shows. The likes of Stella McCartney, Gabriela Hearst and Coach (through its sustainable offshoot, Coachtopia) have had activists dressed in their garments that range between $300 to $18,000 per piece.

These are the very same Stella McCartney and Gabriela Hearst that have both been invested in by luxury business conglomerate LVMH, owned by Bernaud Arnault, the richest man in the world. It is also the same Gabriela Hearst that married into the Hearst family, the world’s 14th most richest family.

Let us not forget that billionaires and their investments are responsible for 3.1 million tonnes of carbon emissions per billionaire annually, over one million times higher than the average for an individual in the bottom 90% of the world (2.76 tonnes of CO2 equivalent).

Another example of elite capture is the growing inclusion of climate activists in social occasions that have historically assembled only the social, economic, and political elite in the same room. Events like the TIME100 Gala, Forbes 30/50 Summit, Vogue Forces for Change party, Green Carpet Fashion Awards have awarded climate activists and given them talk time in the name of distributing attention to the climate movement by using activists as movement proxies.

These companies utilise the pedestalling of individuals, activists, and aspirational lifestyles incentivised by our broken system to the material benefit of the economic elite, big business, and celebrities. To add to the egregiousness of this co-optation, activists have complained (in personal conversations with them) of not being reimbursed for their travel or accommodation to attend some of these functions, leaving them again financially disadvantaged in spite of their willing collaboration with these entities.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Redirecting our attention

Four years ago I had the unfortunate experience of being used by Meta when they reached out to me to create an Instagram reel on climate activism as a way to promote their (then-new) reels feature. At the time, I did not know any better and it seemed harmless because I truly believed it would help the climate cause by bringing more awareness to the issue to Instagram’s large follower base (something that some activists might be able to relate to).

In retrospect, I can’t help but think about how Meta profited off using me and many other activists through such collaborations as a green veneer to indoctrinate hyper consumerism while advertising its tech products. And in case anyone was wondering, no, I did not get paid for making that reel.

Whether they are aware of it or not, climate activists and their social capital have been used as a PR tool by brands to convince the populace of a “better” consumerism that maintains and caters to the pocket and aesthetic of the economic elite.

Bringing attention to this activist co-optation and elite capture is not to place a moral judgement on the means by which these activists are trying to create change, rather it is to highlight the ways in which they are manipulated to help funnel profits to these companies, their investors and top management based on an extractivist, capitalist, neoliberal market logic. This coupling of luxury with sustainability perpetuates existing class inequalities by economically excluding access to certain products for most, while expanding the wealth of the 1%.

Moreover, the resulting exclusion of many from the upholding of these capitalist structures also flies in the face of the climate movement’s active and growing efforts to build solidarity with the working class and poor – undermining the just, livable future these movements are fighting for. Avi Brisman, a justice studies professor, points to a similar concern, stating that “heightened environmental consciousness and concern will [be]… alienating those without the economic means or cultural capital to purchase the latest, greatest, eco-friendly items or engage in the coolest green practices.”

What ultimately happens in this attention-scarce world is that this attention distribution to the climate elite – masqueraded as climate awareness building – distracts from the attention needed to push for a system that limits the egregious amount of wealth and power that celebrities and the economic and political elite in these rooms hold.

It takes the attention away from the 1% hoarding wealth, the taxes they avoid through their ability to access the wealth management and tax evasion industries, and the comparatively little material benefit they provide in terms of funding climate activism and bridging income inequality.

Dealing with elite capture

The fact that the climate movement and its well-meaning activists are getting the attention that is urgently required is, of course, welcome. However, it becomes an issue of impact elitism and the bolstering of our flawed, unequal system when movements and their agents are captured by the 1% that faces little to no accountability. With a sincere appreciation for the laudable work these climate activists have done for the movement, I urge them to refrain from collaborating with the hyper elite and be wary of engaging in elite spaces, to push back against the tide of elite capture, and to:

- hold the 1% accountable

- fight for safeguards that prevent the 1%’s undue influence on political outcomes

- demand for just taxation and a limit on the wealth of the economic elite, and

- call for the creation of a climate justice reparation fund that would be financed by the taxes gained from the elite who contribute the most emissions to the climate crisis

Even if they do decide to continue being in these spaces, I encourage them to push for these measures.

To address elite capture, Táíwò appeals for a “world-making project” or a “constructive approach” that aims at building better structures of social connection and focuses on pursuing specific goals and outcomes, rather than just the “avoidance of ‘complicity’ in injustice or promotion of purely moral and aesthetic principles.”

Pursuing these measures and creating such a fund can help finance climate action and address the needs of the working class and poor. It can shift climate activism and influence from being funded by brands, companies, and conglomerates to a more democratic and just fulfilment of activists’ and movements’ material needs. The responsibility of fighting for such measures does not only fall on activists, but on all of us.

In an ideal world, the system would be equitable and none of us would have to be demanding for such aims. For now, it rests upon us to realise this just world by collectively doing everything we can to fight for what is right, and to build it anew.

What can you do?

Read:

- Limitarianism by Ingrid Robeyns

- Environmentalism and elitism: a conceptual and empirical analysis. Environmental Management by Denton E. Morrison & Riley E. Dunlap

- shado’s Knowledge Page: What is Green Colonialism?

- Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (And Everything Else) by Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò

- “Being-in-the-Room Privilege: Elite Capture and Epistemic Deference” by Olúfémi O. Táíwò

- It Takes Green to Be Green: Environmental Elitism, “Ritual Displays,” and Conspicuous Non-Consumption by Avi Brisman

- Meet the millionaires helping to pay for climate protests by John Shwartz in the New York Times

- Co-Opting Social Movements: How Corporations Profit Off Of Human Rights Issues by J. Weber and Owen Derico

Listen:

- The Gray Area with Sean Illing – Elites have captured identity politics with Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò

- Downstream: Why no one should have more than £10 Million w/ Ingrid Robeyns by Novara Media

- Do ethical billionaires exist? with Swatee Deepak in Venetia La Manna’s All The Small Things Podcast

Watch:

- Should social movement work be paid? By Dean Spade

- On green capitalism: The illusions of green capitalism by Adrienne Buller

Organise:

- Climate Emergency Fund provides grants for disruptive, non-violent climate activism.

- Guerilla Foundation provides grants for radical, grassroot social movements in Europe by raising funds from high net worth individuals and those that have privilege.

- Resource Generation organises young people (18-35) with wealth and/or class privilege and work with other social justice organisations to equitably distribute wealth, land, and power.