This week, members of the Frontline Migrant Health Workers’ Group (FMHWG) are providing oral evidence at the third module of the UK Covid-19 Inquiry, focused on healthcare workers. These hearings, and the inquiry more generally, provide a chance for people at the frontlines of the pandemic to share what happened to them on the public record.

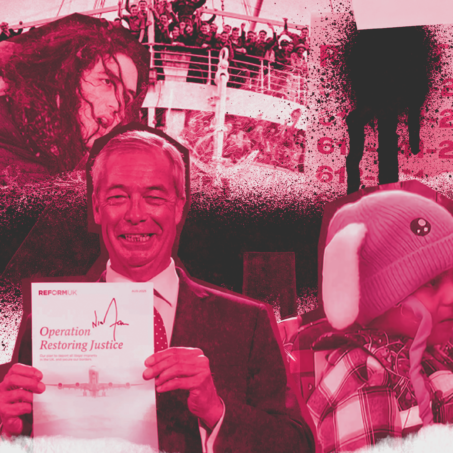

The Inquiry also offers the opportunity for key actors, such as former Prime Minister Boris Johnson and former Health and Social Care Secretary Matt Hancock, to be publicly questioned about their responsibility and complicity in the public health disaster that was the government’s response to the pandemic.

But can an inquiry accurately capture the experiences of the community and bring them the justice they need?

Covid-19 and the Filipino community

The pandemic is the reason I got involved in the migrants’ rights sector. I was a year out of my Masters’ and finishing up a graduate internship at London School of Economics, when I noticed how active a Filipino postgraduate student Facebook group was that I was a part of. Students I knew across London were posting everyday about arranging deliveries for infected community members and sharing fundraisers for Filipinos in the UK who had died of Covid-19. I joined Kanlungan Filipino Consortium, a community organisation supporting Filipino, East, and Southeast Asian migrants and the main organisation providing this support, shortly after.

The pandemic had a devastating impact on the Filipino community. In May 2020, 22% of Covid-19 related deaths amongst NHS nurses were Filipino, despite making up only 3.8% of the NHS workforce. Filipinos, alongside other Black, non-white, and migrant staff, were being deployed en masse to the most dangerous wards, with little to no PPE.

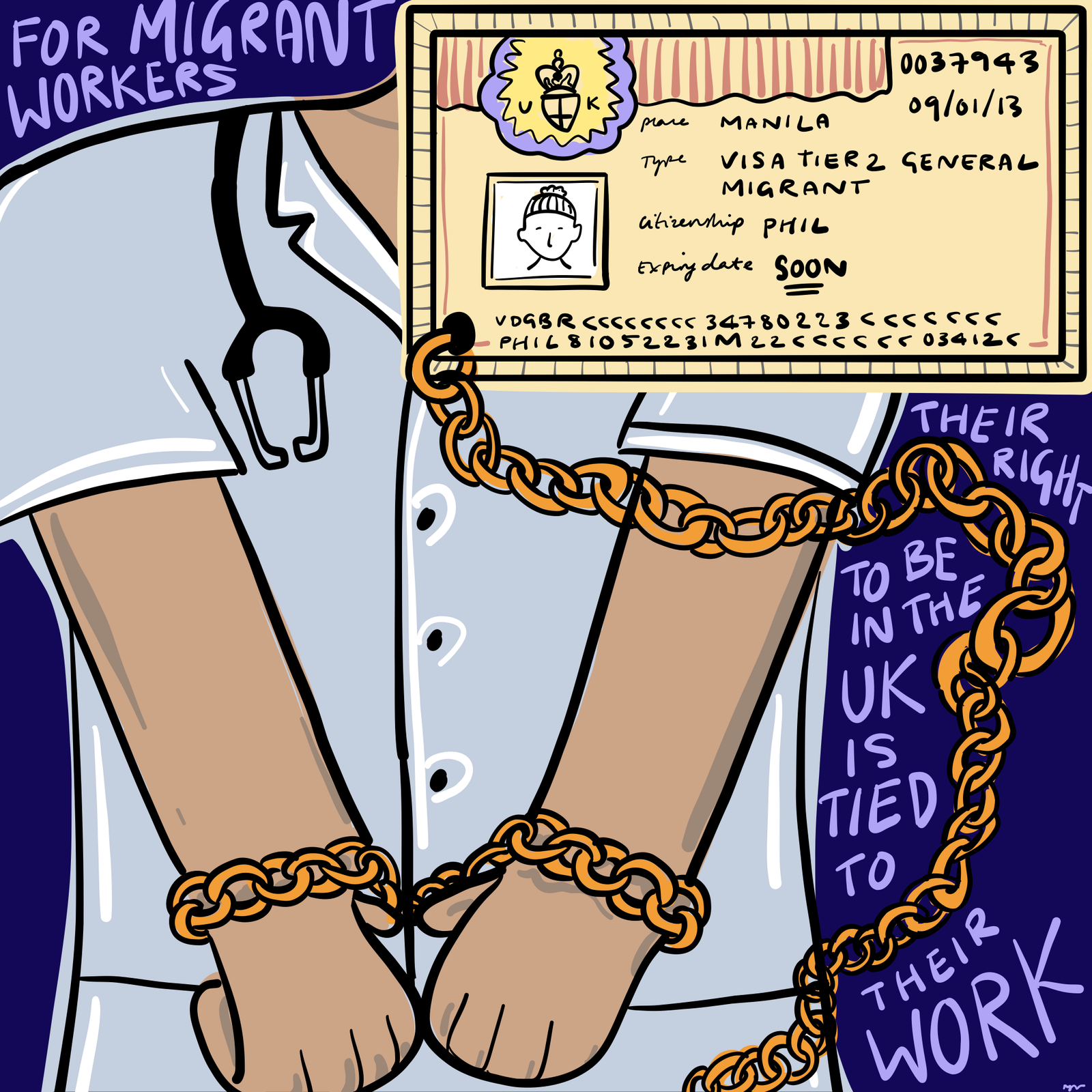

For many migrant workers, whose right to be in the UK is tied to their work, speaking up and complaining – and potentially losing their job and therefore their visa – was terrifying. Migrants on Tier 2 work visas only have 60 days to find a new sponsor: a tight deadline in itself, but an even more stressful one. One Filipino nurse Kanlungan worked with shared the pressures of working during that time, “They would just tell you; you are hired to work here. Just work, I don’t care if you die or not, I don’t care if you are sick or not, just work.”

Covid-19 became the key focus of my work at Kanlungan and an obsession outside of work too. Death, and the threat of it, were omnipresent. Almost every day on social media and in the news, we’d hear of another Filipino migrant in the UK dying of Covid-19. I spoke on the phone to undocumented community members who were so sick they struggled to carry a conversation but couldn’t miss work out of economic necessity. There was no furlough and no sick pay to rely on. For many, even the NHS was too scary to access, out of fear of being reported to the Home Office if they sought medical attention. Some even died because the prospect of being detained and removed was scarier than death.

My experiences of working during the pandemic have had a lasting impact on me. Nothing has shaped my politics more. The injustice of the immigration system, the underfunding of the NHS, Britain’s reliance on overworked, underpaid workers to do the most essential labour, the blatant corruption of private contracts allocated by the government – it all came to light in a violent and shocking way.

The Covid-19 Inquiry

Some inquiries, like Infected Blood Inquiry, have been well received by communities affected. While others, like the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, have been criticised for inadequately capturing the impact on communities or insufficiently engaging with bereaved families. Inquiries don’t have any law enforcement power, but even if they did, carceral punishment is not what would make a material change to the living and working conditions of migrant workers in the UK.

In the months that followed the vaccine rollout, and the years that have passed since, I have felt confused and angry at the rest of the world going back to “normal.” Did we not all just experience the same thing? Are we not collectively traumatised by the mass death and destitution of 2020? This Inquiry is supposed to be an opportunity for answers and accountability, but how can we do that when we haven’t even taken the time to reflect as a society on what happened?

For me, the power of this inquiry, and any inquiry, is to hold collective space for people to reflect on a traumatic event that changed their lives or the lives of their loved ones, friends, or colleagues. But I worry that for the Covid-19 Inquiry, that opportunity is limited by the fact that we, as a capitalist society that values individual productivity above all else, have refused to acknowledge what we lived through and continue to live with. Much like the climate crisis, we know there’s an urgent problem, but we refuse to face it. We don’t want to think about disease, ageing, and disability, nor do we want to think about the people who care for the sick, elderly, and disabled.

Age and disability represent a threat to capitalist notions of productivity that earn participation in society. They also confront us to the disability and old age most of us will face throughout our lives, which many of us find uncomfortable or scary to consider because we see how poorly disabled and old people are treated. As a result, care work, those who provide it, and those who receive it have been systematically devalued and stigmatised.

Kanlungan has been able to provide evidence and testimony for the Inquiry on our community’s experiences from the time, but I’m not convinced anything will actually happen to those responsible for the deaths of Joven Flores, Elvis, Donald Suelto, Elvira Bucu, and the many other Filipino and migrant workers who died of Covid-19.

I don’t have any illusions of Boris Johnson, Matt Hancock, Sajid Javid, Priti Patel, and others being brought to justice – and even if they are, it won’t be a justice I recognise. A prison sentence or fine isn’t what I want, that’s not what will keep our community safe. I want collective liberation, dignity and joy for all, regardless of how or why they came to this country. I want what happened to my community members never to happen again to anyone. A world that requires the death of those who care for us is not a world worth fighting for. I want to remember them tenderly and honour their memories fiercely.

What can you do?

Watch:

- Covid-19 Inquiry hearings for Module 3 on 9 and 10 October: UK Covid-19 Inquiry – YouTube

- “EXPOSED” documentary produced as part of the Nursing Narratives research by Sheffield Hallam University about racism faced by nurses during the pandemic

Read:

- Nursing Narratives: Racism and the Pandemic, report published by Sheffield Hallam University, 2022

- Essential and Invisible: Filipino irregular migrants in the UK’s ongoing COVID-19 crisis, published by Kanlungan, 2021

- A Chance to Feel Safe: Precarious Filipino migrants amidst the UK’s coronavirus outbreak, published by Kanlungan and RAPAR, 2020

- Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History by Catherine Ceniza Choy, Duke University Press, 2023

- Washing our hands of BAME contributions and sacrifices: the inevitable story of COVID-19

Support and donate to:

- Kanlungan Filipino Consortium

- Filipino Domestic Workers Association UK | London

- The Voice of Domestic Workers: Voice of Domestic Workers

- IWGB: Donate · IWGB

- UVW: Donate to support our fight for equality, dignity, and respect! – UVW

- DPAC (Disabled People Against Cuts): DPAC