Food sovereignty definition

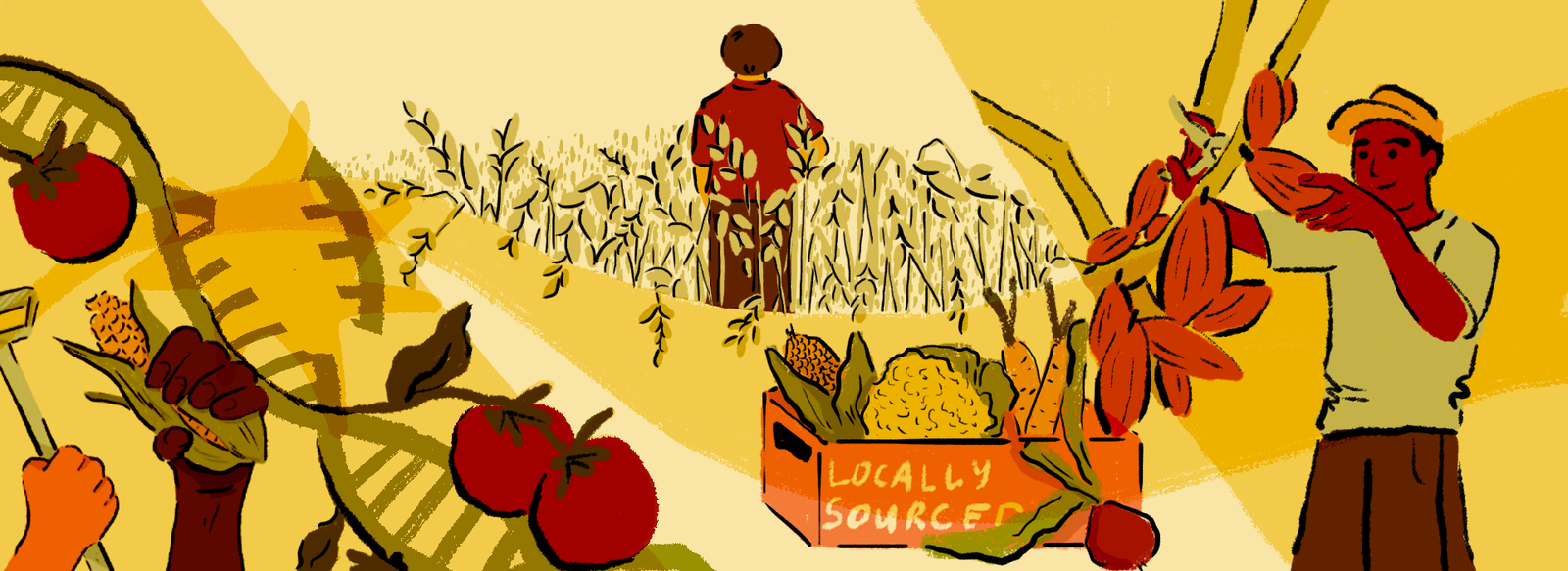

Food sovereignty is the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.

~Declaration of Nyéléni

Although ‘food sovereignty’ is a relatively fresh term on many people’s lips, it actually describes a relationship to food and its production which has characterised human societies since the dawn of agriculture.

Up until very recently, that is.

Today, most of the world’s population have come to depend in one way or another upon an unjust and unsustainable globalised food system; a system which has been shaped by centuries of colonialist, capitalist, and in recent history, neoliberal free market ideology.

In this system, food is produced for trade on international markets, not for people. Industrial-scale agriculture has dominated, at the expense of the small-scale producer; and a myopic capitalist focus on maximising agricultural output has decimated soil health, squeezed genetic biodiversity, and contributed extensively to global greenhouse gas emissions.

Our food has come to be treated first and foremost as a commodity, with a total neglect of the cultural, ecological and genetic heritage of our food, seeds, and traditional farming practises. All while the livelihoods of the farm labourer, butcher and vegetable picker have been trampled into degradation, exploitation and precarity.

The food sovereignty movement seeks to put an end to these injustices, and does so by disrupting unequal power dynamics and by building resilient, just and ecological food systems from the grassroots.

In short, Food Sovereignty has six key principles:

- Providing food for people

- Localising food systems

- Centring local control

- Valuing food providers

- Working with nature

- Building skills and knowledge

Why is Food Sovereignty a global issue?

Food sovereignty is a global issue. We are all engaged in this global food system whether as a producer or consumer, and so cannot separate ourselves from the injustices within it. The reach of multinational corporations and international markets know no bounds, so neither should our commitment to showing solidarity with struggles for food sovereignty in all corners of the globe.

From Indian farmers protesting the rise of neoliberal trade policy in the streets of Delhi, to communities in Palestine defending their farmland from Israeli colonial dispossession; and from the campaign to halt the deregulation of gene-editing in the UK, to protecting the rights of migrant labourers in southern Spain. The struggle for food sovereignty takes many forms, but together they form a global movement united under a common vision for a more ecologically and socially just world.

Who are some of the key leaders in this movement?

Although the practice of food sovereignty is timeless, its development as a concept and its resurgence as a political movement has been led by La Via Campesina – a global alliance representing over 200 million peasant and Indigenous food-producers across 80 different countries. It’s these guardians of knowledge, keepers of seed and stewards of the land who naturally stand at the forefront of the food sovereignty movement.

Last year La Via Campesina celebrated 25 years of collective envisioning and action towards food sovereignty, following the presentation of its Food Sovereignty Declaration at the UN’s second World Food Summit in 1996. Eleven years later in 2007, 500 delegates representing farmers, pastoralists, landless workers, fisher-folk and Indigenous groups came together to meet in the small village of Nyéléni in Mali. Here, they signed the Nyéléni Declaration, a key text which has laid the foundations for defining and mobilising for food sovereignty ever since.

Where is the movement heading?

Small-scale, localised and agroecological food production that works with nature rather than trying to dominate can help mitigate climate breakdown in numerous ways – from building healthy carbon-storing soils and building resilience through supporting biodiversity and genetic variation, to shortening supply chains and reducing the need for transport, storage and packaging.

The value of localised and resilient food systems has also been brought into sharp focus over the course of the coronavirus pandemic. Our over-reliance on volatile global supply chains to put food on our table has led to empty shelves, higher levels of food insecurity, and an increased need for food banks here in the UK.

As we look on towards an uncertain future framed by climate chaos, disease and the mass displacement of people, food sovereignty can offer a real solution and a remedy to a multitude of crises. The closer we are to our food, the closer we can get to achieving a healthier and more just planet.

What can you do?

- Be mindful of where your food comes from, who produced it, who profited from it, and how it was grown, and where possible, support local, small-scale regenerative farms.

- Follow and support workers’ unions like the Landworkers’ Alliance and other La Via Campesina member organisations. You can find LVC member organisations in your region here.

- Read shado’s Seed Sovereignty Knowledge Page

- Support struggles for Food Sovereignty and familiarise yourself with their demands:

- Continued solidarity with the Indian Farmers movement

- Beyond GM campaigns

- Landworkers’ Alliance Vocal for Local campaign

- Sign up to your local veg box schemes, or muck in by volunteering on your local small farms or market garden.

Good social media accounts to follow:

Worldwide:

- A Growing Culture

- La Via Campesina

- Nongmoproject

- Kisan Ekta Morcha (India)

- GRAIN_org

- Fianinternational

In the UK:

- Landworkers’ Alliance

- Growing Communities

- The Gaia Foundation

- Land In Our Names

- FarmsToFeedUs

- Cococollective_org

- Grancomkitchen

- Organicleacommunitygrowers

- Youth_flame

- Gogrowwithlove

- Soul.farm

- Claireratinon

- Heritageseedlibrary

In the US:

- Blackfoodnw

- Usfoodsovalliance

- Soul Fire Farm

- Amber Tamm

- Rock Steady Farm

- The Farmworker Project

- foodworkersalliance

Podcasts on Food Sovereignty:

- For the Wild podcast episodes on Food Sovereignty

- Farmerama

- Food Revolution

- Green Dreamer podcast episodes:

- #283: Sanjay Rawal: Honoring the Native lands and farmworkers who feed us

- #159: How urban farming may be key to reclaiming our food sovereignty

- #325: Karen Washington: Food security, justice, sovereignty

- #319: Errol Schweizer: Navigating the exploitive food system towards worker justice

- #147: Ending settler colonialism to reclaim food justice and sovereignty

- #312: Brian Yazzie: Supporting tribal communities through Indigenous foods