Adèle Oliver and I immediately hit it off over Zoom. A linguist, author, musician, music producer, proud Brummie, Adèle is also what she describes as a “scholar in remission.” This last attribute is evident through her use of ‘affect’ in her new book, Deeping It: Colonialism, Culture & Criminalisation of UK Drill.

In short, affect is about the embodied nature of experience. It is how interactions or events (known as ‘affections’ which can be big or small) affect us deeply in the body and mind. Though it can be situated in emotions like sorrow, pain and pleasure, it’s not an emotion itself: it’s a feeling that shifts something in us. In turn, this shapes our way of being and interacting with the world. I remember reading about affect at university and being so enthralled by the philosophy of embodiment. So when I saw it featured heavily in Adèle’s lines, I was so excited to commend her use of it in the context of drill and Black music culture.

Adèle’s 99 page book packs a punch. Not an academic thinkpiece, connections between colonialism, expression and criminalisation are made instead via interviews with UK drill artists, both up and coming and established. She tells me: “it was really important to show that the people who are making the art also have the knowledge.” This assertion alone already gives insight into the kinds of barriers those making drill music face.

To kick off our chat, we needed to situate ourselves in the genre. We both disclosed our favourite drill songs, mine being ‘Lock Arf’ by Smoke Boys (while they sit across multiple genres, they did influence what UK drill looks like today) and Adèle’s being Birmingham’s very own Trizz with ‘active’.

Drill: the music, the myth, the legend

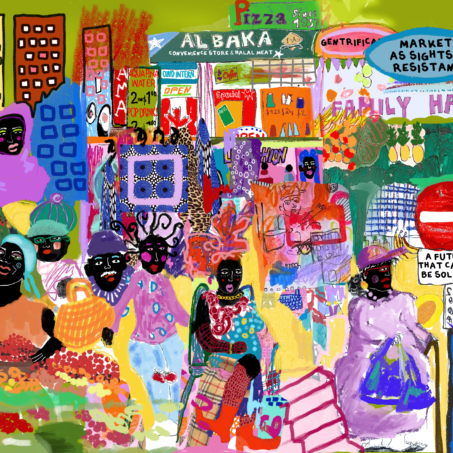

The true musicality of drill, like many Black genres before it, is largely ignored. Drill is a subgenre of rap that originated in Chicago, characterised by its dark, nihilistic lyrical content over ominous and melodic beats. It does not get the credit it deserves for its storytelling, relatability and its stark portrayal of Black British and working class life. In this way, drill acts as a periscope, showing us the inconspicuous ways people are surviving in this system- picking up multiple jobs, working outside of the taxed system and working from early teenagehood to support the household. It also shows us what life is like growing up in underfunded areas, schools, with very little opportunity to make something of yourself. “Drill highlights the consequences of austerity,” Adèle explains. “We have been living in 20 years of this, 14 under Conservative leadership.”

The majority of my teenage years and twenties has been under Tory leadership, a party that champions economic liberalism, social conservatism and restrictionism, particularly of immigration. In those 14 years, I have lived through multiple financial crises, housing crises, healthcare crisis, university fees skyrocketing, low wages, high cost of living, stifling inequality, a hostile environment, increased police power, reduced state support and generally people feeling more hopeless about what the future brings. What drill artists are doing is narrating the fallout of social deprivation and poverty.

They shine light on the realities of people, particularly young Black people, being failed by the system. From education to housing to opportunities (creative or otherwise), to poverty and health – particularly mental health – we hear the tellings of people making something out of nothing. A song that comes to mind is Just Me, Just Us, where Headie One says: “Growing up weren’t all rosy, it was just me and my sisters.” He goes on to detail the pressures of needing to financially support your household so young when you grow up in poverty, and the drug-adjacent path many people take where he is from which often opens them up to exploitation, criminal charges and endangers their life. We hear the current situation of so many faces across the UK neatly wrapped in a melodic BPM and confrontational lyricism

Along with discrediting its musicality, drill is often flattened into a one-dimensional listening. Demonised by politicians and the police alike through the media, reports and court verdicts, drill is positioned as the antithesis to a moral society and is considered a beckoning call for violence. Yet, what is more violent than the system we live in?

Drill is so much more than this. As Adèle says, it spans so much: “including friendship, love, hate, isolation, finding your identity and particularly grief – of friends, family, your youth, innocence and the promises of a future not surrounded by violence – both interpersonally and systemically.”

Adèle continues: “drill’s ability to allow someone to articulate their own situation so precisely and rawly makes drill a periscope into the art of worldbuilding.” By touching on subjects which are often ignored by wider society, drill forces listeners to reckon with the stark reality of life in Britain. If we can name these experiences, we can go about starting to change them. Particularly in the UK, where self expression is stifled and tight-lipped, drill’s uncut delivery is a refreshing tap into the fire that sits deep within us. Drill’s ability to energise and activate us is exactly what we need to challenge such a pervasive system.

Policy, Policing and Criminalisation: The three horsemen of Britain’s colonial legacy

The construction of Blackness as deviant means a genre like drill, which is created by working class Black people in some of the most deprived areas of cities across the world, will always be met with increased suspicion from the state. Drill music is considered rebellious, violent and confronting – in the same way Black people are perceived by the state. Because the majority of drill has remained within the Black and working class communities that create and shape the genre, it means the genre itself is associated with this perception of Blackness.

Music and dance produced by colonised and/or enslaved Black people across the Black diaspora has historically been perceived as inherently dangerous. Black music has not been traditionally considered an expressive art form but as a call to arms.

During the 18th century in Jamaica, it was noted that drums, trumpets and dance were prohibited on the island because they were thought to incite rebellion. Similarly, in 1688, a law came into force in Barbados that ordered slave owners to search slave quarters weekly and confiscate and burn any instruments.

Drill isn’t the first sound pioneered by Black people to be criminalised by the British government. “Crime and criminality is an ever shifting goal post that moves with the perceived dangerousness of colonised people,” Adèle says. Jazz, roots reggae and sound system culture, jungle, acid and garage as well as pirate radio and grime have all been subject to policing and unfair criminalisation on British soils – reflecting what happened on the colonies generations before.

What is different with drill however is the kind of policing and criminalisation is more institutional – enshrined in law, policy and state databases. We have seen the Met police collaborate with streaming websites including YouTube to permanently remove drill videos, destroying live archives of this artform. We have seen shows and tours get cancelled, drill artists constantly surveilled through the Met police’s specialist team Project Alpha and the Gangs Matrix, imprisoned and deported. We see here how different arms of the state collaborate to eradicate the production and longevity of this artform. The moral panic around drill is astounding.

The role of art in making the revolution irresistible

In times of economic, political and social downtown, arts and culture is the first thing to be cut, and yet it is one of the only beacons of hope in times as bleak as ours.

For Black people, living in a world that functions through anti-Blackness and white supremacy, the embodiment of our culture, values and community in our arts is an intentional effort to remain rooted in our heritage and history. There is an incessant need for Black people to feel, and by extension of that, feel alive. Like our instruments, there’s a certain aliveness to drums and percussion that can be used to communicate, activate and unite us.

Art is a living practice: it’s constantly moving. This is especially true in Black music genres and their cultures. Adèle and I speak about Notting Hill Carnival being a great example of this. It is one of the few places you allow the music to completely take you over and for you to be completely free.

“The history of carnival was in direct rebellion against enslavement,” Adèle explains. “J’ouvert was outlawed in Trinidad in 1846 for fear of inciting slave rebellions, and still to this day these cultural expressions are being targeted by the police.” J’ouvert usually marks the start of carnival as it’s done the day before. It’s an expression of liberation from the oppression of slave masters and an honouring of the ancestors who’ve come before them. This tradition still continues in Trinidad, across the Caribbean, and is also marked here at Notting Hill Carnival.

Notting Hill Carnival is the largest Black cultural event in the UK and it is policed significantly more than majority White festivals of its size and/or larger. The racist perception that large numbers of Black people will result in criminality forms the backbone of policing, policy and law.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Drill has been met with similar levels of censorship and policing, of both the artform and its people. And there are further similarities: both drill and Carnival are to be felt, rather than perceived or consumed. Both are built on camaraderie and community. Adèle expands: “there’s so much potential and power in how much you lean on other people. While there may be drill artists at the forefront, they always move and perform as a group. There’s someone doing ad libs, someone dancing and you see they all have each other’s backs.”

When we talk about collective action or resistance against prejudice, drill gives a huge canvas for people articulating their story in the way that feels most authentic to them. In relation to community building, everyone has a part to play in making drill, no person’s part is smaller than the other and because of this, everyone’s contributions to making a group of performance what it is, is respected and appreciated. Drill is not about leaving behind the people who were with you during rough personal or societal times; it’s about making a way for everyone to eat. This is what makes drill so powerful and far reaching with people across the globe.

Blame the system not the art: a deep dive into ‘Art not Evidence’

Every generation has its resistance music. In the 70s-80s we had roots reggae. In the noughties it was grime. In the 80s, Smiley Culture’s iconic Police Officer song called out racist police brutality at the time. Some decades later, grime single Routine Check by the Mitchell Brothers, Kano and The Streets was released, talking about the racialised frequent stop and searches Black men in particular experience. It was where I learned the police term ‘IC3’ in reference to a Black person.

Adèle and I speak about drill being the resistance music of our generation. Specifically the UK’s style of drill, has been exported globally to places like Ghana, Brazil, Australia, Sudan, Albania where artists, predominantly from working class backgrounds, are taking their own spin at the genre to narrate life there and call out the failings of their own governments and societies. This shows how drill comes from a long history of Black music, not only being a catalyst for social change, but the voice of the people.

The threat drill poses by calling out oppressive systemic issues like racism, poverty, policing, state negligence, has led to the extensive criminalisation of drill and the use of lyrics, videos and audio recordings held up in court as viable evidence to convict. To fight for the right to Freedom of Expression, the ‘Art not Evidence’ campaign was born. Made up of lawyers, academics, journalists, people who have worked in the industry and musicians including Adèle, the mission of this campaign is to fight for a fairer criminal justice system by advocating for a restriction on the use of creative and artistic expression as evidence in criminal trials.

I particularly love this campaign because it’s the first of its kind to campaign against the criminalisation of drill in the UK, and it’s so necessary. Their collaborative approach to this campaign by working with musicians like Digga D and Giggs, community groups and human rights organisations to campaign for law reform is especially admirable because it takes the problem from a community level to an institutional one, centring the people (musicians) who are most affected by the draconian legal system.

A standout case in this is the Manchester 10: a group of 10 Black men all sentenced under conspiracy of GBH and attempted murder because they were sharing drill lyrics in a Whatsapp group chat. The group were considered a gang by the police and that allowed the criminal justice system to prosecute them collectively, under something known as “joint enterprise.”

The young men did not do anything. They were not in a gang (as much as the police tried to say they were); they did not own weapons, nor were they planning to retaliate. In reality they were actually just friends coping with the recent loss of a friend in a group chat, who were made the face of the sensationalised idea that drill breeds violence and criminality.

As a musician herself, Adèle feels like the criminalisation of drill has wider consequences for all artists and musicians. “The criminalisation is anti-Black, but if you care about art and expression, regardless of your background, you should be backing it, you should be shouting about it, especially if you exploit Black art,” she says.

It sets a dangerous precedent that our right to self expression can be taken away at any time. Art is the embodiment of expression. If we allow drill to go down, who’s to say what genre will be next? Where will this actually end? To stifle the conditions of expression through the criminal justice system will only spread to other facets of our human rights in society, just like it has with our right to protest.

Drill, the multifaceted agitator – what’s its future?

After chatting for nearly two hours, Adèle and I both agreed we should let each other go, but I couldn’t do that without first asking Adèle what her hopes for the future of drill are. “I really want to see drill credited as an artform and a cathartic form of self expression,” she responds. “I want to see drill collaborations we wouldn’t even conceptualise – like in an orchestra, a stage performance, bringing it into poetry, as an anthology studied in school, or even how it would work blended with other genres. I want the possibilities to be endless.”

For Adèle, writing this book was to give name to the oppressive systems that collaborate to suck the life out of living, expression and our futures. It is about making the connections intentionally and by result, proving that how we got here isn’t by chance, but comes from a long history of colonisation and racism, with our society built off the back of that. At times it can feel easier to overlook what is really happening, but when we do this, we only live with the consequences of not collectively changing our realities for the better. As Adèle says, “when you really start deeping it, you realise it really is that deep.”

What can you do?

Here are Adèle’s top 3 recommendations for getting into drill music:

- Next Up- S3-E21, Pt.1 – Trills + Pt.2

- Don’t Panic- Smoke Boys (previously Section Boys) + honourable mention to Delete My Number

- Made in the Pyrex – Digga D

- Honourable mention to Harlem Spartans, particularly ‘Where it Started’, ‘Grip and Ride’, ‘Still On the O’

Here are the Adèle’s favourite authors, podcasts, artists (in any sense), pieces of writing on these topics:

- Dub: Soundscapes and Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae by Michael Veal

- Blues People by LeRoi Jones

- Small Axe by Steve McQueen – particularly the Lovers Rock episode

- The Black Atlantic by Paul Gilroy. There’s nice chapter in about music and album covers

- Field Ramble podcast with Aniefiok Ekpoudom

- Reprezent Radio: Amber w/ Art Not Evidence

- Part of art or part of life? Rap lyrics in criminal trials

What else can you do?

- Read Adèle’s culture shifting book Deeping It: Colonialism, Culture & Criminalisation of UK Drill

- Follow, like and support the Art Not Evidence campaign and sign their open letter

- Check out the Art Not Evidence webpage for more resources on the campaign, artists features and press

- Read their new study Compound Justice

- Check out their Channel 4 news feature with Digga D

Organisations to follow:

- Kids of colour

- 4Front project

- Harm to Healing

- No More Exclusions

- CAPE (Community Action on Prison expansion)

- JENGbA (Joint Enterprise No Guilty by Association)

- UFFC (United Friends and Family Campaign)

- Cradle community

- Abolitionist futures

- Healing Justice London

- Skin Deep Mag

- MAIA

- BLAM UK

- Voices that Shake