Since the overturn of Roe v. Wade in the United States, many individuals are now grappling with the reality of their reproductive rights being stripped away overnight. Without Roe v. Wade being codified on a federal level, 13 states have trigger laws that immediately went into effect or will go into effect, with more conservative leaning states being highly likely to pass restrictive anti-abortion/anti-choice laws.

Unfortunately, even before the devastating political loss of Roe v. Wade, the most vulnerable populations in the United States have consistently dealt with the reality of controlled reproduction. Black and Indigenous women, undocumented immigrants, and incarcerated women are a few of the populations who have been disproportionately targeted in the fight against reproductive justice. What’s worse is that for many of these communities, speaking up and out is not welcomed, and is considered taboo.

Secrets and secret keeping is a necessity in a world with so many taboos, where folks are denigrated for daring to be themselves. Deesha Philyaw’s debut short story collection, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, pulls the curtain back on secrets and secret keeping, focusing on the lives of women in the Black Evangelical church. Each story allows the reader to glimpse into the lives of several women and understand secrets they speak only to themselves or while in community with each other.

This intimate account does not shy away from narratives about sex. For so many individuals discussions about sexuality and bodies can be filled with shame, but Deesha sees Black women in all of our fullness and complexity.

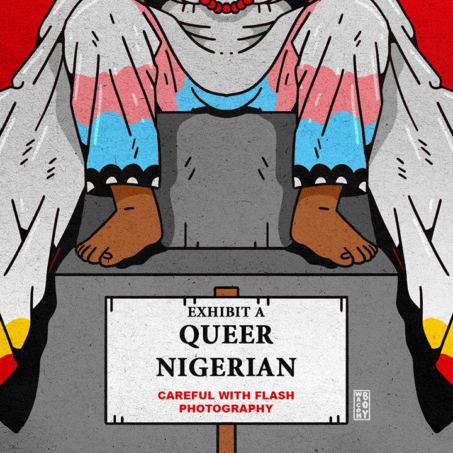

As soon as the book opens, we have a queer relationship presented to us, which, in a community still confronting homophobia, is incredibly refreshing. This story details the relationship between two women, one who is in love with the other, the other who is in love with the idea of finding her perfect Christian husband. For her, non-heterosexual sex becomes a vehicle to maintain her virginity as she waits for God to send the perfect partner her way.

When I ask Deesha about her inclusion of Black female queer characters in her collection, she tells me that the decision was organic, noting that in the Black church, while queer identifying individuals are the most hidden, Black queer women are especially relegated to the sidelines.

“Gay men can lead the choirs and all of those things, they just don’t bring their partners to church. It’s a don’t ask, don’t tell kind of thing. But Black queer women are practically invisible,” Deesha explains. “So you can’t talk about Black women and secrets and secret keeping without including queer women, because they are forced to keep secrets more than anybody else.”

In a space where there is an expectation of abstinence prior to marriage, in order to avoid temptation, many women in the Black, Evangelical Christian church end up spending time with other Black women. And as Deesha notes mischievously, “Something’s bound to jump off, right?”

And jump off it does. There are several stories detailing the experiences of Black queer women who grew up in the Black church. One notes the differences in family lives that two women navigate in their relationship as they build a home within and for each other. Another story details the thoughts of a grandmother tackling her granddaughter’s sexuality, which becomes more apparent as she reads through diary entries about her granddaughter’s desire for the Church’s first lady, which ultimately culminates in a deadly revelation.

In conversations about reproductive rights, the traditional Christian perspective is definitely overrepresented, as other religious leaders have spoken out in support of Roe v. Wade, but what’s apparent in this collection of stories is how ideas relating to sexuality and gender are reinforced in and out of the church, particularly through the elder, maternal figures – a feature Deesha describes as intentional.

“I think mothers transmit cultures often in a way that fathers don’t,” she muses. “And it’s sad too, that when we think about patriarchal messages in particular, our mothers should be our first allies and our first teachers about fighting patriarchy and white supremacy and all of its different manifestations. But a lot of times, as we well know, women – and particularly our mothers – can perpetuate that.”

A large gap exists between ourselves, our mothers and our grandmothers. Gen Z and millennials are generally more open about sexual health and sexuality; Gen X is somewhere in the middle, and the Boomer generation views these topics as more private, despite the fact that they were the ones who fought for the right for all us to have access to abortion and family planning services – though it’s a fight that Gen Z and millennials have inherited once again.

Whether it’s from family members, friends or society at large, from a young age we learn that we should be wary of our desires. Moreover, conversations surrounding reproductive health even in medical contexts, particularly for people with uteruses, can still be uncomfortable and taboo.

The dismal lack of comprehensive sex education becomes increasingly apparent when a majority cisgender, male identifying, law making body cannot even comprehend simple facts about menstruation. “I’m sorry we have to break down Biology 101 on national television, but in case no one has informed [Greg Abbott] before in his life, six weeks pregnant means two weeks late for your period,” Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said in response to Texas’ abortion ban.

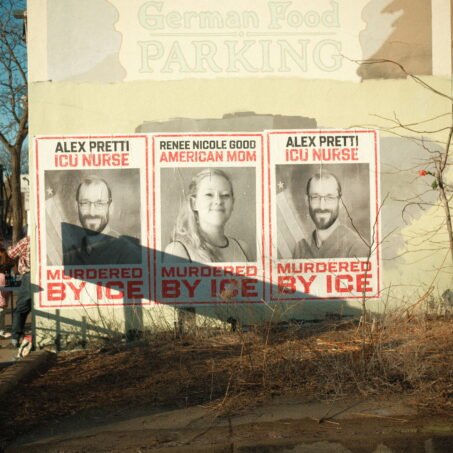

In the midst of the slogans, hashtags, and think pieces, there are very fatal consequences, particularly for working class and historically marginalised groups. It’s an issue that Black women should be at the forefront of, because forced reproduction and sterilisation have been a reality since the first enslaved Black Americans were trafficked to the US through the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade.

Unfortunately, when it comes to questions relating to motherhood, Black women and our motherhood stories are often neglected. Even now, when we see the individuals who are speaking out in the mainstream about what life in a post-Roe world may look like, the most vulnerable voices are not the ones being heard.

“We talk about reproductive rights, but not reproductive justice. Our focus should be on reproductive justice, because the reproductive rights conversation is a much smaller conversation and it doesn’t have the reach that a reproductive justice conversation has,” Deesha says.

Outside of the realm of choice and agency, we are seeing the effects of what forced reproduction can bring in a society without social safety nets, and where those who are poor or working class are viewed as disposable. What happens to the folks in Texas? What happens to pregnant people who cannot afford to travel across state lines to access services?

For now, white cisgender women appear to have the loudest voices in these movements, but they are not the only ones whose lives are at stake. When reflecting on this intersectional fail, she notes a quote from Lonnae O’Neal in her book, I’m Every Woman: Remixed Stories of Marriage, Motherhood, and Work, stating that, Black women should be the ones leading these efforts because “we’ve sat with the questions longer than anyone has.”

The lack of inclusion of marginalised voices, particularly those of Black and Indigenous women as well as the LGBTQIA+ community, is yet another failure in a women’s movement that does not prioritise intersectionality and consistently sees white women’s experiences of womanhood as universal. Commenting on the women’s marches that first began in 2017, she calls to mind an image of a Black women with a protest sign that said, “Don’t forget: White women voted for Trump,” which aptly summarises this disappointing disconnect within feminist movements.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Now navigating life post-Roe, Deesha admits that there is a necessity for her to write the stories she feels need to be told. “I was definitely late to the party in understanding what was at risk with Roe not being codified. I feel more vulnerable now because this giant step backwards has implications beyond Roe. There’s so much at stake,” she tells me. “There’s a greater urgency for today that I think is showing up in my writing and in my writing practice.”

This reality is another reason why The Secret Lives of Church Ladies is a critical piece of literature. Deesha is a contemporary Black writer who gives Black women and our experiences the centre stage in a world where this is not often the case.

What can you do?

- Read The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw.

- Follow Deesha Philyaw on Instagram.

- If you are financially able, support pro choice organisations in your local area, especially if you live in states where those are most affected by abortion bans. Organisations like Indigenous women rising, The Mariposa Fund, and New Voices for Reproductive Justice, specifically help persons with uteruses in Indigenous, Black and undocumented communities.

- Donate your time as a Volunteer Clinic Escort with an organisation like planned parenthood or at your local clinic. Oftentimes, anti-choice protesters will stand outside of these clinics to verbally discourage and shame folks from accessing the help they need. As a clinic escort, you offer security and reassurance by walking patients into the clinic, which can make a world of difference.

- Voice your support for pro choice candidates and legislation at the ballet box, especially if you live in battleground/purple states.

- Help voting efforts by canvassing with local groups that help get folks in marginalised communities registered to vote. Many of these issues are connected and one way anti-choice legislators seek to maintain control is through voter suppression, which makes initiatives targeted towards fair voting even more crucial.

- We all can continue to educate ourselves as well, to fully understand the vast history of forced reproduction in the United States. Instead of relying on a whitewashed reference to the Handmaid’s tale to express discontent at the current state of affairs, read more intersectional works and listen to the voices of those most affected. Authors like Octavia Butler and Kimberlé Crenshaw are great places to start, and this list by Black Women Radicals has more extensive resources for an intersectional deep dive.