Outside of the South Asian community and diaspora, Navratri – Nav meaning nine, and Ratri meaning night – is one of the lesser known Hindu festivals. While the exact date is determined by the Hindu calendar, it tends to fall between September and October. For many, it’s the crown jewel of Hindu celebrations: over nine days and nights, Hindus all over the world dance, sing and fast to celebrate the feminine divine. In essence, Navratri is a Hindu festival for the multiple female goddesses that exist in Hindu mythology, as well as one that honours the girls and womxn on Earth.

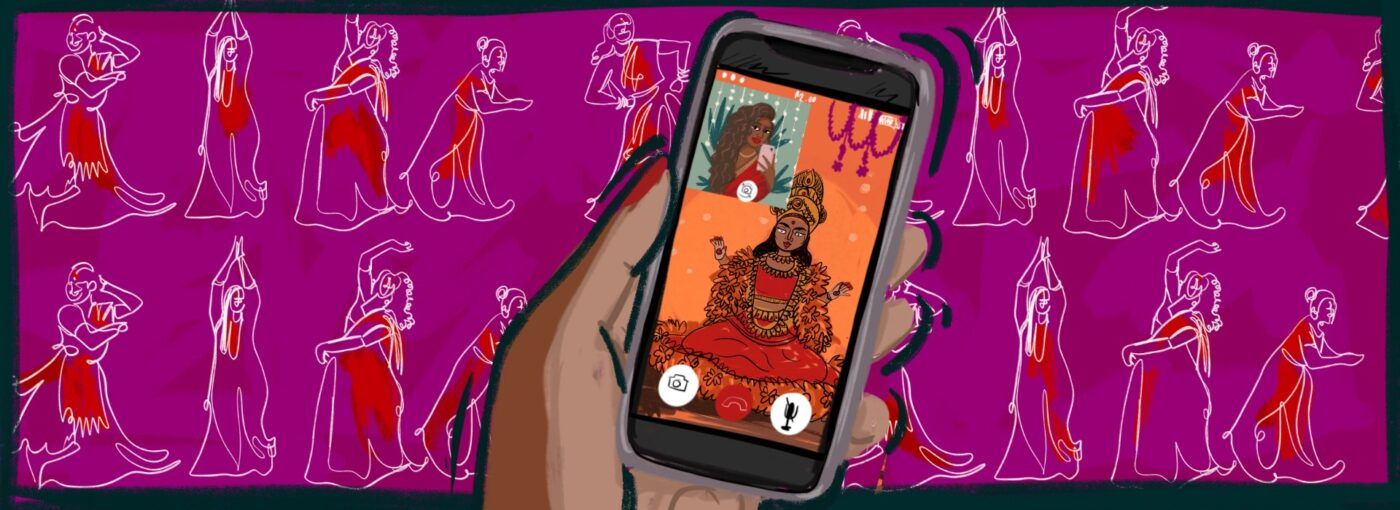

It’s no surprise that this year, as 2020 threw us around between multiple lockdowns, the South Asian community collectively bit their lips as it emerged that usual Navratri celebrations could not go ahead. Things moved swiftly to the virtual realm; the jarring juxtaposition between the ancient traditions of Navratri and the usual glitches of Zoom were at once difficult to adjust to, but necessary to preserve some semblance of normality.

With Hinduism being one of the oldest religions in the world, with multiple factions, subcultures and, unfortunately, looming shadows of caste, Navratri has evolved into a festival that is celebrated in a thousand different ways. What united them all this year was that everything had to be done at a physical distance. From two distinct cultural communities of South Asia, here are the dispatches on how Navratri adapted to the pandemic:

West India:

Gujarat, a state in Western India, is the birthplace of Dandiya Raas, a folk dance that marks the nine nights of Navratri. For a lot of Gujarati Hindus, a typical Navratri includes a prayer session – an aarti – either at home or in a community space followed by a long night of Dandiya Raas, which is also colloquially known as Garba. The best way to describe Garba is energetic: it’s a rhythmic dance, where you repeat a single step, and it is performed in a circle around an altar of a female deity. The dance is usually led by women in the community, keeping true to Navratri being a celebration of the feminine. While in India, Garba has taken on Disco and Bollywood forms as well, the diaspora are often keen to hold on to the incredibly traditional versions. At its easiest, it’s a simple rhythm of clapping while moving in a circle. At its hardest, it’s a series of rapid turns and runs that only masters can get involved in – one wrong step can disrupt the flow of the whole circle. Looking up Garba is a fun YouTube hole to fall into.

Navratri crept up on us this year, as did the whole back-end of 2020 . Neelam Keshwala, the founder of the creative community DON’T SLEEP ON US, posted about her homebound Navratri on Instagram. Zoom, a tool preserved for professional, formal interactions, was taking on a whole new face for Neelam and many others, a very real blurring of worlds for many in the diaspora.

An ugly part of the celebrations that many don’t discuss is that the Hindu faith has always stipulated that people who are menstruating should not be allowed to participate in anything holy. In extreme cases, girls and womxn are not allowed to cook for their families while they are on their periods, because it is considered ‘unclean’, and thus ‘unholy’. It’s a grey area that many are beginning to question the relevance of in the modern world. During Navratri, it feels highly ironic to be excluding those because of something that is key to their femininity.

Digitisation and physical separation as an effect of COVID-19 have had two distinct impacts. Jaineesha Patel, a renowned make-up artist, has been having the difficult conversation about period stigma on her Instagram for two years, much to the disapproval of some of her followers. For her, Navratri-from-home this year was a real breakthrough: “It becomes even more difficult to exclude people when you’re not physically leaving home for Aarti or Garba,” she says. Most Gujarati Hindus have a small altar in their living rooms – a Sthapana – where they would have shifted their Navratri festivities towards. “Our living rooms became our sacred places of worship. Are you really going to tell your family members to go to a different part of the house while you pray? We are not uncompassionate enough to do that to one another.”

That said, the Sthapana itself is considered to be as holy as a temple, and so some girls and womxn still found themselves relegated to bedrooms while other family members prayed. It is easy to assume that it is the older generation pushing these ideas onto younger generations, but in fact, young people in the diaspora might be upholding these cultural norms themselves. They’re ultimately anxious about disrespecting traditions, and appearing to cherry-pick the traditions that they want to be part of. “So many people are still worried about touching something holy because of everything they have been told,” Jaineesha continues. “There is still so much fear. But that fear can lead to disconnection from the culture. Garba is supposed to be an empowering activity, but alienating certain individuals does the opposite.”

South India:

Navaratri celebrations in South India take on a very different colour to those held in the North. Religious worship focuses on the different forms of Devi, who encompasses the feminine forms of creativity and energy. Indeed, each of the nine days has a unique significance, with elaborate poojas (ritualistic ceremonies) dedicated to different goddesses and items. Another distinguishing feature about a South Indian Navratri is the grand display of dolls, which are intricately arranged to reflect timeless folklore stories that are recollected throughout the festivities. Evenings are usually spent visiting family and friends to admire their collections, all whilst sharing festive food, partaking in a few short customs and most importantly of all, catching up with loved ones. This year however, things were very different.

The aforementioned pujas were muted and simplified, with none of the usual ostentation that makes the festival so special. “It just didn’t feel the same,” said Anuradha Arun, 44, who usually celebrates Navratri with her extended family in Bangalore, India. “There were none of the usual grand processions and cultural activities. Even getting pooja items were difficult, as the usual flowers, fruit-sellers and doll-sellers weren’t out in full force due to coronavirus concerns.”

As a result, many families were unable to carry out their usual traditions. Chandrika Samprathi, 50, is also from Bangalore. She spoke about missing out on a particularly special family custom. “My mum, who sadly passed away, used to buy my daughter a new doll every year. I’ve been trying to keep that culture going ever since, as I know how much it means to our family. It was very sad that we were unable to do that this time round. The scare of getting coronavirus was just too much.”

Indeed, even though India is no longer in lockdown, both Anuradha’s and Chandrika’s families decided to keep celebrations scaled down and limited to immediate family only, but this was not an easy decision.

Chandrika said: “We are used to inviting around 100 to 150 people home for the festival on any one day to come and see our dolls and enjoy dinner with us, but we missed out on everything this year. We know we could have gone to the temple, which is usually such a big part of our week, but this was just a risk we were not willing to take, especially with so many vulnerable elders in the house.”

Yet Hindu families still tried to find silver linings throughout the festivities. All over the world, virtual celebrations took place, from sharing photos of doll collections on group WhatsApp chats, to arranging zoom calls to catch-up with those they usually would have seen. Anuradha added: “Whilst the online celebrations were devoid of the proximity and warmth that this time of year is usually filled with, it still meant a lot to spend time preparing for poojas and cooking with our loved ones. But when so many people are experiencing such great loss, we’re grateful to have even had that.”

See more of Tinuke’s work on her instagram HERE

See more of Sharlene’s writing HERE