The clicking of the remote as you flip through the endless thumbnails of content on a streaming platform is, by now, a unifying experience across continents. Most times for me, this leads to a rewatch of a favourite, but sometimes something new wins the contest. This leads me to a random midweek evening, unwinding with a new Netflix show Next Gen Chef in one of my favourite genres: cooking competitions.

As is the general format of these shows, we are slowly introduced to the contestants and their family through endearing photo montages played over personal interviews. One contestant, 23-year-old Ilke Schaaf, explains that she is an American of white Afrikaner South African and Namibian heritage. Within her proud recollection of this, her grandmother features prominently as a source of cultural memory centred on cooking and the transfer of recipes considered uniquely Afrikaans. Curious about how this story would be told, I kept watching.

Rewritten histories make the sweetest stories

In one challenge, contestants were tasked with creating a dish that showcases their heritage incorporated into American Southern cooking. Ilke presented a meat pie with a Bobotie mince filling.

Recalling this recipe passed down from her grandmother, she refers to it as an “Afrikaans curry,” which won her the chance to lead the other chefs for the rest of the challenge. Since this challenge foregrounds heritage, I anticipated a larger explanation of the dish’s history even if a distorted version claiming cute exchanges of culinary tips between colonisers and the enslaved was offered. The history ended with Ilke’s grandmother and her endearing culinary pursuits across apartheid South Africa and Namibia.

My first thought when she explained her heritage was apartheid. The trifecta of Afrikaner-South African-Namibian heritage for a young white woman who now lives as an American, reminded me of the often-overlooked point in our dialogues about the past: apartheid was not only a colonial project in South Africa, but in Southern Africa, with Namibia bearing the brunt of white Afrikaner colonial expansion that inserted white Afrikaner culture into a society already violated by German colonialism.

The nexus of that duality that Ilke now expresses with pride, is attached to a profoundly devastating history of violence. This legacy, while it erases many people like me, now propels its white descendants to global platforms to retell this history, heavily redacted with all the warm-and-fuzzies needed for an audience in search of a feel-good watch to have with dinner.

Escaping accountability and other recipes of whiteness

I grew up in South Africa as a Coloured person in the ‘90s, in the newborn afterlife of apartheid – a time of reclamation, reflection, and re-education. As we got to work, with the best of intentions, to process and heal from our traumatic past, South Africans could once again proclaim their identities with pride. Public holidays commemorating the pride and pain of the past were introduced to bind a new social compact that acknowledges where we come from, to ensure that we never forget the tragedy of such unfathomable inhumanity.

One instrument used in our attempt at national healing and accountability was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The TRC was a court-like body set up to pursue restorative justice in the aftermath of South African apartheid. What many now look back on as a failure delivered little accountability, and even less healing. For those testifying and witnessing, the simultaneous recollection and obfuscation of the brutality committed by white state actors and civilians alike retraumatised those who still live without the closure the TRC was meant to provide.

This great escape from accountability allowed white Afrikaners to thrive in post-apartheid South Africa, under a government that stunned the world with a call for unity that washed them clean of the stigma of their actions. The pariahs of the ‘80s were reborn in a world of opportunity that not only left their lives but also their culture untouched.

Washing heritage gives whiteness an easy out

Today, South Africa celebrates Heritage Day on the 24th September each year. The day is widely regarded as a celebration of culture, which for most people involves dressing in traditional regalia and cooking cultural foods.

Culture here is specifically in reference to what is broadly termed “African culture.” This involves varied practices and artefacts that link modern South Africans, of various ethnic groups, to long histories of cultural formation, and hopes to display the continuity and preservation of traditions that have resisted erasure across numerous colonial onslaughts.

With the help of corporate whitewashing, a controversial solution has unofficially rebranded Heritage Day as “Braai Day” – which references South Africa’s version of a barbeque, which is said to unite all South Africans around our love of grilling meat.

This rebrand gives white people generally, and white Afrikaners specifically, a comfortable way out of facing the implications of heritage in a country where their legacy is largely one of destroying said heritage. With eyes wide shut, they are coddled within the glowing warmth of the embers of a farcical South Africanness that does not, and should not, engage seriously with its own history. In this way, food has been made an accomplice to the erasure of colonial legacies that continue to victimise its original targets and egg on its beneficiaries to follow their noses wherever they lead them.

This conundrum of heritage, and the celebration thereof, has stalked me, and so many people classified Coloured people, for related but severely different reasons to white Afrikaners. In the ongoing process of reclamation South Africans engage with in a post-apartheid society, it took me reaching early-to-mid adulthood to realise that the culture I was said to be without was in fact stolen and rebranded by colonisers who installed themselves as custodians of that culture, which I believed we were scavenging on.

Cooking the (recipe) books for a whiter palate

Within this deeply disorienting and alienating experience, food has always been an anchor of identity for me. If I knew nothing else about my history, heritage and culture, I knew that I was of a people known for their way with food.

In South Africa, although often denigrated for being without culture, Coloured people and more specifically Cape Coloured people are known for their culinary prowess to such an extent that the celebration teeters on the edge of exoticisation. Within this, an offshoot of Orientalist discourse makes of Muslim Coloured people, largely descended from enslaved South-East Asians, culinary sorcerers who conjure intricate flavour and colour profiles with expert knowledge of spices and seasonings such as turmeric, cinnamon, cloves, cardamom, coriander and cumin, to name a few. If I knew nothing else about myself, I knew that we make some of the most flavourful and fragrant food in South Africa.

This knowing has, however, always come up against a problem of (mis)representation through cultural media. The notion of Afrikaans cooking has enjoyed the help of millions of Rands in broadcast and publishing budgets aimed at sustaining white Afrikaner cultural production. While many cookbooks claim to offer a comprehensive collection of “South African” recipes, one of the most well-known culinary publications in South Africa – Cook and Enjoy It – was first published in Afrikaans in 1951. As official South African values were defined by the precepts of Afrikanerdom at the time, while erasing everyone else, South African meant white Afrikaner.

A paper trail of colonial erasure hiding in plain sight

Bobotie, which inspired Ilke’s dish on Next Gen Chef, is often at the centre of contention when South Africans try to decide on a national dish. Known to many as a cultural mainstay of white Afrikaners, the dish consists of a curried beef mince mixture featuring turmeric, bay leaves, and curry powder, topped with an egg custard and baked. The version that most South Africans would have tasted, from the hands of white Afrikaners, is often sweetened through the use of apricots and muted by modest inclusion of spice. Justifiably, with this recipe, it is not widely enjoyed and is shelved as a weird white people thing.

According to Wikipedia: “The origin of the word bobotie is contentious. The Afrikaans etymological dictionary claims that the probable origin is the Malayan word boemboe, meaning curry spices. Others think it to have originated from bobotok, an Indonesian dish which consisted of totally different ingredients. The first recipe for bobotie appeared in a Dutch cookbook in 1609. Afterwards, it was taken to South Africa and adopted by the Cape Malay community.” This statement itself is a roadmap of colonial erasure that persists to this day to conceal the history that makes this dish so contentious.

Food features prominently in white Afrikaner cultural imagination as a site of innovation. A part of the “valiant” story of Afrikaner colonial expansion rests on the narrative trope of white Afrikaner women cooking and baking for the survival of their men and the economic survival of their communities in the face of British imperialism. The story of their rise to the seat of power is often oversimplified to be the outcome of bake sales and cookouts, which serve as symbols of the community’s divine perseverance.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

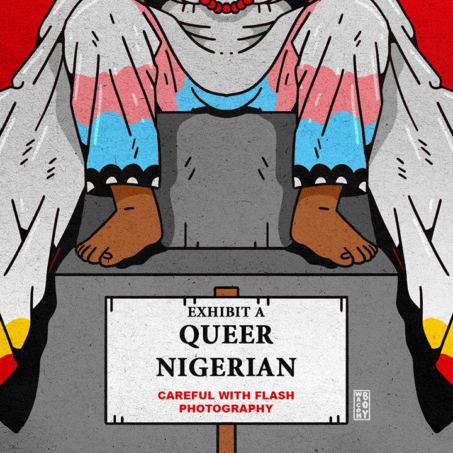

While there has been progress in how the cultural production industry engages with history, the convenient workaround that still absolves whiteness is to create separate platforms that enable us to showcase our culinary talents within their respective histories, while the dots remain blissfully disconnected.

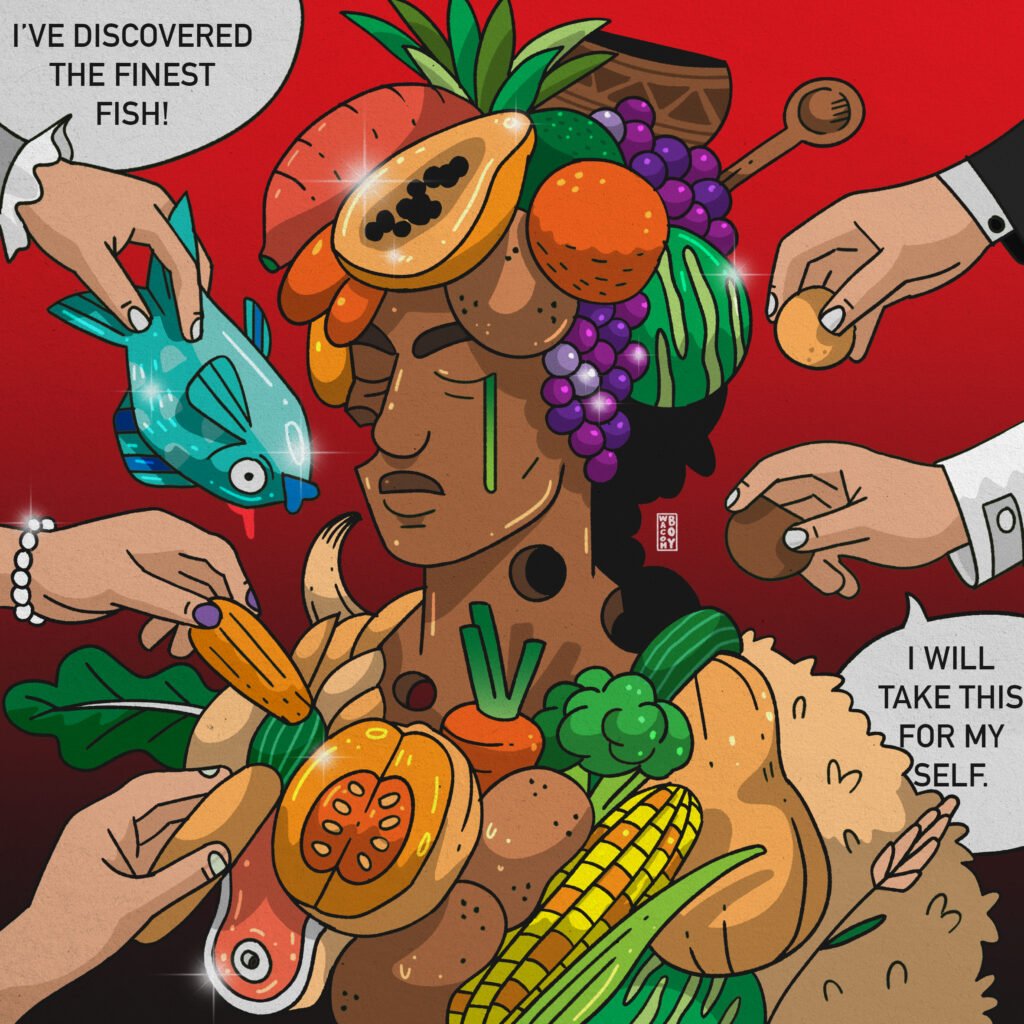

This disconnection allows the persistence of the impression that we practice a confused colonial culture when we cook our ancestral food. In all versions of Afrikaner food history, the innovation of enslaved and Indigenous people lurks in the corner. Whether it is through the inconvenience of historical memory, or the presence of a juniorised Black person preparing the ingredients off camera, pretending to learn from someone who stole and botched their recipes.

Ending apartheid includes remembering the cultures it destroys

In this global moment, where a genocide of the Palestinians under a brutal Israeli apartheid regime continues, this story issues a warning and an invitation to us all. The warning sounds a message that when colonial perpetrators of crimes against humanity are allowed to walk away from accountability with all their possessions and memories intact, they will continue to enjoy the privilege of rewriting histories that eventually wash our collective memories of brutality away. This is particularly sinister in the context of Donald Trump’s decision to grant white Afrikaners asylum on the claim that they are being persecuted in South Africa.

The show is also complicit in rebranding colonial theft as an interesting cultural practice of white Afrikaners who are now free to bring their “‘gifts’ to the world, while the victims of their crimes could only dream of receiving that level of interest. Significantly, the prize money for the competition is $500,000 – an amount that can change lives, showing again how the fruits of colonial misinformation continue to hand out chances for further enrichment to the beneficiaries of colonialism, while its victims languish in obscurity.

In response to this atrocity of memory, we are invited, in our activism against the colonialism that seeks to wipe Palestinians from the face of the earth, to not only insist on saving their lives but also their memories and cultures. As South African apartheid shows us, 31 years later, it will continue to replicate itself at various levels of social organisation, with repeated attempts to erase the histories that implicate its beneficiaries in its crimes.

Though I now do this work relentlessly, in some ways, it is too late. I now embody an ethnic identity plagued with the weight of enduring misinformation and dehumanisation through centuries of dispossession of land, property, and culture. The myths have stuck to us now. This will happen again, if we are not vigilant and brave enough to resist and strike down every single aspect of colonialism which threatens to rebrand even Palestinian food as a bounty of Israeli innovation.

In pursuit of a more honest recollection of Indigenous culinary histories at the nexus of colonial destruction, I ask, with tears in my eyes: “What do white people know about spices?”

What can you do?

- Food as the language of occupation: Culinary Zionism and the colonisation of Palestinian foodby Mouna Madanat

- Cape Malay food has a dark past, delicious future in South Africa by Griffin Shea

- The colour of Cape Malay culture by Haji Mohamed Dawjee

- You can read other shado articles by Jamil HERE