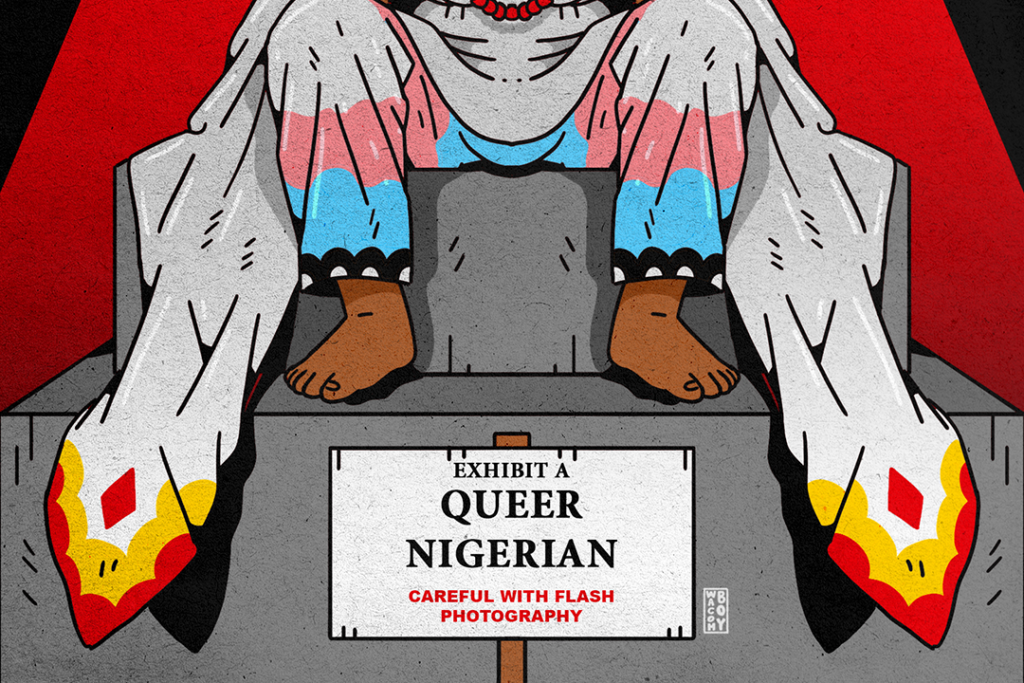

Lagos is one of the queerest places in the world. Queerness here thrives precisely because it doesn’t always call itself that. It exists in a very specific condition where it is felt, perceived, and practised, but not acknowledged.

Moreover, many of our cultural practices, from the way we dress, how we use language, to the way we interact with space, suggest that queerness is deeply entrenched in our day-to-day lives, whether we choose to admit it or not. So, what does it mean to bring visibility – particularly based on overt identity labels – to what is already known and felt, if not overtly acknowledged?

Over the past week, I have seen various content creators who position themselves as ‘representations’ of queerness post videos about queerness in Nigeria. These creators engage in content creation with the belief that their presence in these spaces is necessary a form of representation for queerness, blackness, Africanness, Nigerianness, *insert other marketable identity label that is never truly defined and/or does not seem to be understood past limited lived experiences*, etc.

When prolific use of social media intersects with the urge to commodify queerness, there is a rapid rise in the belief that queer visibility, and the consequent visibility of the queer communities they claim to represent, is the solution to queer liberation. I do not disagree that visibility and representation can be a part of what brings about great progress for the human rights of queer people, but the operative word there is ‘part’ of the work. It requires a level of tact that I do not often see in the content being pushed out.

Before I go deeper into this, a majority of this article focuses on queerness in Nigeria – Lagos, particularly, and the nuances within that milieu. This is largely because these are the areas these content creators speak to/from, but also because I spend a lot of time in Lagos myself, and have done extensive research on queerness in Nigeria. I do believe these logics transcend this region, but it goes without saying that if none of the parameters of the article apply or resonate with your context, take what does, and leave the rest.

How does visibility work?

There are various legal impediments to queer people’s human rights in Nigeria, most recently the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act, 2014. These laws don’t just simply dictate how queer people should live their lives in Nigeria, but also determine social and cultural attitudes towards queer people. They lead to self-surveillance and self-regulation among the population, and have allowed the state to govern the lives of queer people from a distance by encouraging citizens to erase, marginalise, and discriminate against queer people.

Visibility can be a great tool to challenge these forms of erasure and discrimination. Queer people in Nigeria know this more than many. Between activists demanding to be seen during the #EndSARS protests against police brutality in Nigeria, and countless efforts in the NGO, activism, and arts spaces, queer people in Nigeria are demanding to be seen. They consistently and insistently show up to spaces and scenarios where they are erased to embody a right to appear, actively asserting their visibility and right to protection.

However, the problem lies in treating this visibility as the entirety of the work, and in conceptualising it as the only precursor to queer liberation. This is especially insidious when it is adopted, commodified, commercialised, and proliferated by the #OutAndProud queer content creators hoping to use this demand for visibility for views and clout.

There has been a recent rise in LGBTQ+ content creators – often living abroad – who create content centred on being #OutAndProud. They offer advice to queer people; show themselves existing ‘freely’ in ostensibly ‘free’ and ‘utopic’ Western states; and document their daily lives as an aesthetic for public consumption.

Again, this is seen as somehow necessary for queer liberation, and supposedly seeing them existing in this way is what queer people need in order to see that it is possible to be queer. They buy into the false equivalency between what is possible and what is seen. We think that queer people cannot be what they cannot see, implicitly suggesting that what is seen is all that is real and all that matters.

Queerness as a commodity

Once again, I am not disputing the need for representation and visibility, but there is an increasing commodification of queerness, particularly pertaining to the spaces queer people occupy, due to an increase in tourism and a transition from spaces being community-focused, to being increasingly entrepreneurial in order to drive profit.

Spaces now find it important to show their cultural credentials by providing seemingly boundaried and safe areas for marginalised people. These spaces present the presence of marginalised groups as signals of ‘inclusion’ and ‘diversity’, therefore attractive to a cosmopolitan visitor looking for a good time. While this can be seen as a good thing in some cases, it is also fundamentally about profit.

For content creators who are visitors to these spaces, they are offered a fascinating look into how marginalised (in this case, queer) people live that they are not accustomed to experiencing or seeing. And for content creators who already exist within these spaces, they offer a way for curious people on the outside to see how they live. Either way, it must be documented and shared because it is an attractive hook.

In recent years, and especially in Lagos, with the influx of the African diaspora and international patrons, especially during peak seasons around December, popularly known as ‘Detty December,’ the spaces queer people occupy have become more visible in this consumer culture, acting as symbols of cosmopolitanism, acceptance, and inclusivity for these tourists. Detty December is often a series of parties, concerts, and events in Lagos, and other West African cities, such as Accra, usually primarily aimed at international visitors and tourists. The term “detty” (dirty) expresses the idea of indulgence, fun, and letting loose in the spirit of the holiday season.

Organisers of these events and spaces can bring together queer and ethnic spaces, and reduce their individual meanings and the complexities of the people within them, making them interchangeable objects of entertainment in the urban sightseeing experience, and encourage profit for these establishments. This fuels the cosmopolitan mindset that entails a fascination with other cultures, and the freedom to explore them.

Capitalising on the good vs bad state

Coming from or living in a country that is presumed ‘better’ and ‘safer’ for queer people, such as the UK, USA, or Canada, some content creators present insights and experiences from spaces like Nigeria that are presumed ‘bad’ and ‘unsafe’, often without any critical engagement. Content creators in Nigeria can also capitalise on this dichotomy of ‘good’ vs ‘bad’ states by providing sensationalised content, also without any critical engagement. This provides data to a curious international traveller who wants to signal their chicness by consuming other cultures.

So, engaging with these spaces, and content-ifying it to show these experiences, become paramount for the financial gain of both the establishments and the content creators. The sensationalised story can reach a wide audience because it buys into the voyeuristic view of how the West sees spaces that criminalise LGBTQ+ people. It presents these expressions as miraculous exceptions that need to be consumed and experienced.

On the other hand, it also triggers a flood of queerphobic violence from local actors who reject these forms of visibility and inclusion. These vitriolic attacks do not end with the content creators, but extend to queer people at large. Either way, engagement is up, curiosities are piqued, and flat and reductive discussions are had. In an age where attention on social media serves as a source of income, more attention equals more financial gain, no matter the cost.

Visibility without infrastructure

I have seen various content creators discuss the few in/formal infrastructures that queer people in Lagos have developed for themselves to experience joy. These content creators are fascinated by it because of their assumptions about Nigeria, and so they try to bring visibility to the fact that queer people are, in fact, being queer in Lagos – what a shocker, right? While these creators do not always give specific details of these spaces, it doesn’t help when they have content-ified their entire trip and shown and named all the spaces they have been to. It’s only a matter of time before the connections are made.

The issue is not simply extending visibility to these spaces; it is providing visibility to these spaces as ‘queer spaces’. Naming them as ‘queer’, in such an overt way, means mainstream events that have managed to get by without the burden of labelling them as queer, are placed under scrutiny.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

It is quite lazy to approach providing visibility in this way because it lacks any awareness of what structures – if any – are in place to handle the consequences of such exsposure in a space where queerness is criminalised.

While queer activists and communities in Nigeria are deeply resilient, active, and persistent, the in/formal infrastructures that have developed are not equipped to withstand the repercussions of the visibility these content creators provide. The reasons for this are numerous, and I do not have the room to get into them here, but it is clear these structures remain underdeveloped in part because such visibility often exacerbates risks rather than alleviating them.

Over the years, we have seen the consequences of visibility when adequate infrastructure to accommodate such visibility has not been established. A recent prominent example is in Ghana, where an LGBTQ+ centre intended to be a safe space for queer people had to be shut down shortly after opening because of the attention it received, leading to multiple threats and abuse. Along with other measures to garner favour with homophobic people, politicians have used this to discuss legislation that bans LGBTQ+ advocacy and other impediments to queer rights. They explicitly stated the opening of this centre as an issue in its Memorandum. This undoubtedly has ripple effects on surrounding areas like Nigeria, where a bill to ban crossdressing has been discussed to impede the rights of queer people further.

Therefore, bringing visibility to the few informal infrastructures that queer people in spaces of criminality have developed to find joy is NOT doing what you think it’s doing. This is especially true if your intended audience is not within the group you’re speaking about. Those who NEED to know about these structures already know about them. In fact, often content creators speak to the fact that they only heard about these events via word of mouth. So, who does the visibility you’re providing through the video serve? What are you doing for the queer communities in Lagos by making your TikTok videos about their parties?

It’s also not lost on me that the people that position themselves in this the most are people that are elite (adjacent), either by virtue of their class position or their proximity to Western spaces. They are in better positions to consume these spaces and their inhabitants as voyeuristic visitors before returning to their default spaces. They are able to bring back tales of their journeys; stories of ethnic, othered communities that live in ways that would be inconceivable by the West due to previous misconceptions. They can proliferate these stories, but the consequences do not touch them because they have left.

I could also say a lot about how these events they are ‘revealing’ and proliferating, in themselves, are also products of the commercialisation and commodification of queer safety. The notion of safety is not something that these events are particularly creating; rather, they are establishing a sense of security that is already embedded in the socio-economic realities of the elite spaces they choose to host their events in. These events then provide a packaged form of safety that is constrained within these elite frameworks, and sold back to a specific subset of (elite adjacent) queer people who can afford the financial and logistical measures it takes to access them. But this, in itself, needs a whole book to tease out the nuances, so I will not digress.

Visibility is not survival; survival is

In There’s a Disco Ball Between Us: A Theory of Black Gay Life, Jafari Allen notes: “As the 1980s wore on, we learned, tragically, that ‘visibility’ is emphatically not ‘survival’. Survival is … To be seen does not automatically conjure positive relationality or solidarity.” Visibility does not necessarily equate to safety, security or survival. In many instances, increased visibility can intensify the vulnerability experienced rather than provide protection. Especially in spaces where the infrastructures aren’t developed yet.

There are various queer events in Lagos that thrive in spaces free from the burdens of visibility. Yet the recent interest from Western media and content creators in documenting and broadcasting these spaces transforms them into public spectacles. They lose the intimacy and sanctuary that being out of view affords.

We have seen countless times that these media driven visibility efforts lack the necessary mechanisms to protect people who face the personal and societal repercussions of this exposure. If we want the visibility so bad, we need to support the groups to develop the infrastructure to withstand the backlash. Every time queer people in Nigeria go viral, we are reminded of this lack of infrastructure, so it should be at the top of our priorities – or at least, should be up there with our desires for visibility.

Visibility is not the work. Put the camera down for a second, turn off the ring light, and get back to work!

What can you do?

- Watch Kito: Blackmailing LGBT people in Nigeria

- Read Vagabonds by Eloghosa Osunde

- Listen to Odejuma | The Politics of Being Queer and Nigerian with Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi

- Read Invisibility and power in the digital age: issues for feminist and queer narratology by Tory Young

- Read There’s a Disco Ball Between Us: A Theory of Black Gay Life by Jafari Allen

- Read Cities, Queer Space, and the Cosmopolitan Tourist by Dereka Rushbrook

- Read Queer In/Visibility in Africa by Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi

- Read The Shit and the Sunrise by Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi and Ayodele Olofintuade