The #StopAsianHate hashtag gained traction in the US this year after an uptick in violent attacks on the Asian community. Notably this included elderly Asian Americans, with the reported attacks occurring almost daily by the middle of March, as reported by Asian American news outlet, NextShark. Since this increase in hate crimes, activists around the globe have been trying to draw attention to increased racism towards people of East and South East Asian (ESEA) heritage and appearance, with limited success. The incident that brought this widespread issue out of the echo chamber was the tragic killing of eight people, of whom six were ESEA women, at spas in Atlanta, Georgia, on Tuesday 16th March.

In the UK, pre-Atlanta, there was a small amount of coverage of the increase in hate incidents over the past few months, focusing mainly on the violent attacks against Singaporean student Jonathan Mok in London and the Chinese professor Peng Wang in Southampton. The London Metropolitan Police data from 2020 saw an overall increase of 74% in reported hate incidents from January-December compared with the previous year. Police figures reported from other UK regions (such as Essex and the Midlands), though less comprehensive, indicate that similar increases in anti-ESEA hate crime were observed nationwide in 2020.

Despite this increase being largely ignored by mainstream publications, organisations like besea.n (Britain’s East and South East Asian Network), End the Virus of Racism and CARG (COVID Anti-Racism Group) have been raising awareness of anti-ESEA racism since at least July 2020.

It’s a strange time for the ESEA diaspora at the moment. Our causes are suddenly being amplified left, right and centre, but this notoriety comes off the back of a horrible tragedy that has left a devastating hole in the Asian American community in Atlanta and impacted the mental wellbeing of many members of the global community. There is a collective sense not only of grief and trauma, but also fear, anger and frustration.

Fear because we live in a global society where we can draw a clear trajectory from every day, biased, bigoted behaviour to actual targeted, violent hate where people lose their lives. Fear because we can’t protect our friends and our families and people who look like us, because we know that anyone is at risk for the colour of their skin. Anger and frustration because it shouldn’t take a mass shooting for our voices to be heard and finally brought into the mainstream consciousness.

Due to the blame game perpetrated by the west against China, racism towards ESEAs began to enter public consciousness last year. However, this discourse has been sorely lacking in its ability to address the structural and systemic drivers behind this anti-Asian discrimination, focusing instead on sensationalising only the stories that deal with extreme, pandemic-related violence. Prior to the pandemic, racism against ESEAs has gone largely under-reported in the UK media. Last summer, the organisation End the Virus of Racism was approached by a television producer concerning a documentary to explore anti-ESEA racism, but then ultimately told it would not be ‘relevant to the news cycle’ unless an actual killing had occurred. And now here we are, only a few months later: Vicha Ratanapakdee. Xiaojie Tan. Daoyou Feng. Hyun Jung Grant. Soon Chung Park. Suncha Kim. Yong Yue. Sia Marie Xiong.

In the UK, a BBC Panorama documentary aired earlier this month was intended to highlight the issue of anti-ESEA racism. The production team approached several ESEA organisations for interviews, with individuals reporting distressing experiences recounting their trauma and being asked to provide photo and video evidence of incidents. When the programme aired, however, there was a distinct lack of focus on the proven systemic inequalities that people from ESEA backgrounds face in the UK,instead treating the COVID-related incidents as an isolated phenomenon.

However, ESEA communities have been faced discrimination and erasure in the UK for a long time prior to the outbreak. A key reason for this is a gaping hole in national statistics and a frustrating lack of consensus around the language we use to identify ourselves. While Asian Americans have laid claim to the acronym AAPI(Asian American and Pacific Islander) – in which both groups have much in the way of shared solidarity and experience – that acronym is not so useful to a UK demographic. Most of the time when you hear the phrase ‘British Asian’, people will often think of people with South Asian heritage, as Indians make up the biggest ethnic minority group in the UK, followed by Pakistanis. For example, the BBC Asia Network is predominantly focused around South Asian culture. A 2018 Ofcom report on diversity on BBC One and Two found that just 66 ESEA people featured on screen, in a sample size that covered the peak time from 6pm until midnight over a period of four weeks, across a range of programmes including news.

In both the 2011 and 2021 Census for England and Wales, only one specific East Asian classification (Chinese) and all the other countries of East and Southeast Asia (sixteen in total) lumped together: Other Asian.

Are we not ‘othered’ enough in society as it is?

How can we possibly make data-driven policy changes to tackle socio-economic issues affecting specific ethnic groups if we don’t even distinguish between them statistically at national level? Looking across the pond, a 2020 Smithsonian APA webinar, ‘The Model Minority Myth’, given by Dr. Kiona, Liz Kleinrock and Takeru Nagayoshi, demonstrated the positive outcome of using disaggregated data when discussing Asian ethnicity as it helps to demonstrate various disparities between different Asian ethnic groups living in the US, helping to dispel the ‘model minority’ myth. In the UK, we can only dream of this.

A critical example is a 2020 report by Public Health England, which concluded that ethnic minorities were more likely to die from contracting COVID-19 than the white population. While the report did make some attempt to examine the reasons behind why this is the case, all signs point to the fact that we simply don’t have enough data on different ethnic minority communities to understand the jobs they are doing, the medical care they are or aren’t receiving, or their economic and family situations. In terms of ESEAs, the report in question only mentioned Chinese ethnicities specifically. Why is that the case? We know that Filipinos are the second highest ethnic minority working in the NHS, for example. We also know that 1 in 3 nurses who have died from COVID-19 are Filipinos, according to research conducted by the organisation Kanlungan Filipino Consortium.

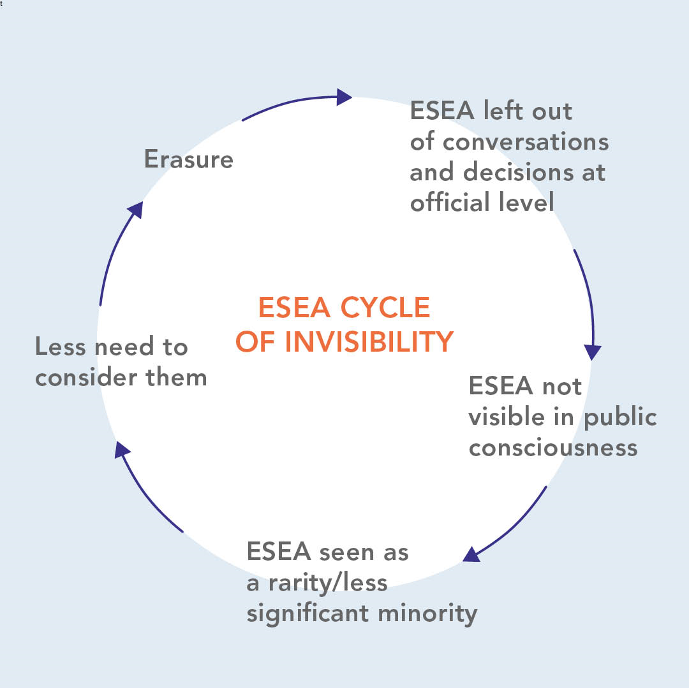

Credit: ESEA Cycle of Invisibility, by Amy Phung & Mai-Anh Peterson

In 2020, an Ipsos Mori poll found that 1 in 7 people in the UK would intentionally avoid people of Chinese origin or appearance. Deeply entrenched, historical sinophobia (fear of and discrimination against Chinese people) compounded by geopolitical relations with the CCP and an overall inability to distinguish different ethnicities, means that anybody who is perceived to be of ESEA origin, including Chinese people, is at risk of racist treatment. For this reason, we should and must continue to use correct terminology, in the interests of all demographics. Additionally, focusing on geographic regions – East Asia and South East Asia – takes the emphasis away from skin colour, though it is critical that we are cognisant of the ways in which colourism impacts and marginalises darker skinned ESEAs.

Finally, this problem is underpinned by a lack of positive representation to balance out the negative attention we have been receiving. Enter besea.n, an organisation that carries out advocacy at public and private level, but also works to reclaim the narrative by spotlighting the UK ESEA community on an online platform. Across the country, different ESEA groups are mobilising to speak out about their experiences and push for the visibility they deserve. Ultimately, the work of ESEA orgs in the UK such as the ones mentioned, as well as SEEAC (South East and East Asian Centre), ESAS (East and Southeast Asian Scotland) and BEATS (British East and Southeast Asians in Theatre and on Screen), including the research and outreach that they carry out, should have garnered much more support and attention than it has.

The bottom line is this: we, as ESEA people, should not need to provide receipts of our trauma to be taken seriously. The UK needs its own racial discourse around ESEA communities, and it needs it now.

See more of Natsumi’s work on instagram