The UK’s first Black Month was celebrated in October of 1987. Prompted by the growing shame among Black children of their African identities and ancestry, Ghanaian born Akyaaba Addai Sebo devised a series of events to challenge the growing identity crisis among the Black British youth. 2020 marks the 33rd anniversary of this cultural space dedicated to celebrating Blackness and instilling pride among Black people. Since its inception, Black History Month has been used to celebrate the contributions of Africans and people of African descent to British society – and to the world.

There is something to be said about the relegation of Black history (which is, in fact, world history) to a single month in the year and the whitewashing it undergoes to maintain the UK’s illusion of innocence. There is also much to be said about how the world so readily questions the validity of the month (does “we don’t have a white history month” sound familiar?). Both merit their own explorations and to do so would constitute several essays worth of unpacking. My goal here, though, is to unpack the (mal)practices of different institutions as they scramble to organise commemorative events every single year.

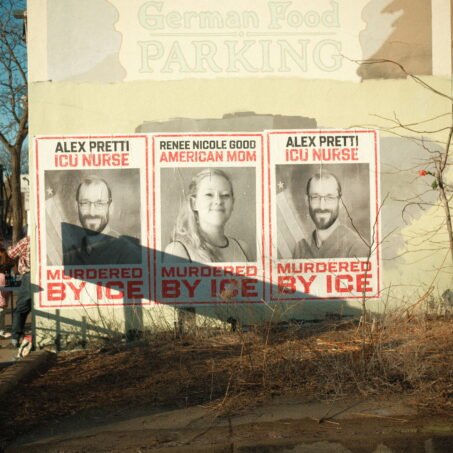

Collective Black grief spilled over following the very public brutalisation of Black people and manifested through different forms of resistance. These included radical self-care, the Fed-Up uprising, and various forms of online activism, such as the plethora of Instagram infographics aimed at educating the world on racism and anti-racism. Such work, mostly being done by Black people, requires emotional and intellectual labour from people who are on the receiving end of systemic violence. That is to say, gripped by both a pandemic and collective grief, Black people were still ‘managing’ their emotions and producing and presenting knowledge for the world’s consumption.

We have this year also witnessed a rise in ‘allyship’, performative and otherwise, from non-Black people and majority white institutions in the wake of George Floyd’s death. People were quick to do (or portray doing) the work of anti-racism; sales piqued for books such as Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race and How to be an Antiracist, and companies and institutions upped their efforts to have diversity and inclusion conversations. Of course, allyship demands constant learning and correction, so educator Marie Beecham created a resource in which she outlined the Dos and Don’ts of allyship where she noted importantly:

Don’t expect Black people to educate you. The expectation for Black people to explain themselves and their suffering to you is an example of white supremacy.”

Black people are being faced with hypervisibility in the workplace after the events of the year. Despite the infographics and events aimed at anti-racism and increasing diversity and inclusion, events have largely depended on Black labour.

Priscilla, who works as a corporate consultant, said that she has suddenly been approached, by people she had never spoken to before, about putting on events for diversity and inclusion – often at short notice. The work being asked of her had become overwhelming and she had been advised to put her foot down: “sometimes you have to redirect them to material and let them do the work”. She speaks of having been included in many spaces this year for diversity and inclusion purposes, but stresses “Black people’s work is not just about that. Don’t limit us, we are more than that.”

Mica, an assistant research psychologist, relates similar experiences. After having pointed out the violence within a space that was designed to improve race relations, she became the go-to for all things racism; “but not everyone is trying to be your racism mentor!” Mica’s workplace had also been organising internal diversity and inclusion training events for staff, but she says that the event organiser told her from the offset; “we don’t need a budget for this.”

Black History Month has been central to institutions’ public relations in 2020. Yet history repeats itself: like in previous years, these same institutions have scrambled to organise last minute, budgetless and tokenistic initiatives for a cultural event that occurs every year. “I’ve stopped replying to emails now,” says Mica. “You don’t need Black people to come and tell you about their traumas, you are the ones that need to be striving to be better.”

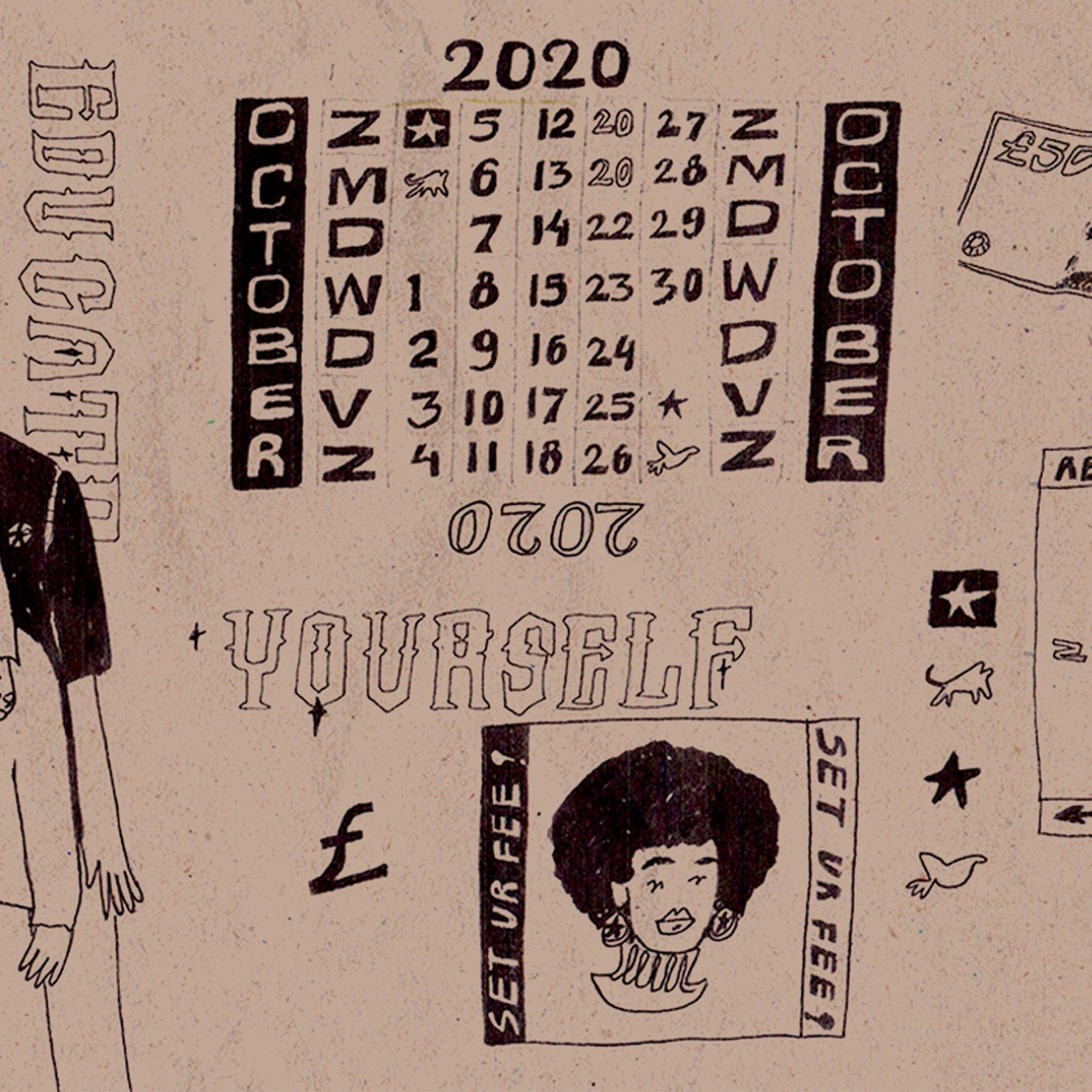

I, too, have been a victim of such demands from the higher education institution that I used to attend. It seemed at the time like an unproblematic, even progressive, request. It had also been packaged as a ‘great opportunity’ for me to showcase my work as an artist in front of a ‘receptive’ crowd. It had not occurred to me that I should be compensated for the labour. I don’t think it had occurred to the event producers either – and, if it had, they hadn’t bothered to discuss that budget with me. I was excited, though: somehow convinced that the invitation was a validation of my intellect; that it was compensation enough.

But even in receptive crowds, whiteness is inescapable. There I was, another Black person on the panel, speaking to mostly white people about erasure and other forms of violence, yet unsure if this would fundamentally change any of their lives. I was taken aback when a white woman approached me tearfully to tell me how she had no idea about all the things we had to endure. Unequipped and performing what has for so long been expected of Black women, I held it together for the both of us and comforted her. In this space, where I had vulnerably laid out personal and collective trauma, she, and the other white people in the room, had been the priority.

Herein lies the multi-layered and dissimulated (to those who, like me, didn’t know any better) violence of these platforms. I have since learned new vocabulary and have come to understand that ‘holding it together’ after micro- and macro-aggressions is neither a strength nor a virtue. White entitlement to the products of Black physical, intellectual and emotional labour is a colonial vestige, the fact of demanding it during Black History Month is simply to add insult to injury. With all the resources that have circulated freely, especially this year, it is clear that anti-racist “efforts” are done to placate Black people.

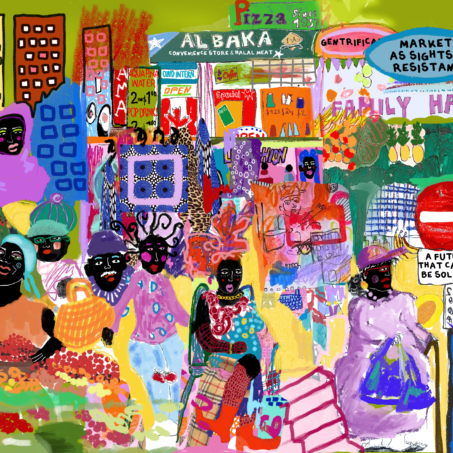

Black people in the UK still suffer large pay penalties in comparison to their white counterparts. Caribbean and African households earn 20p and 10p respectively for every £1 earned in a white household. You’d think the long history of forced labour that occurred under colonialism and slavery seems like an obvious reason for institutions not to demand free labour, let alone on this month – but it is an indicator of how little things have really changed. To stand ‘symbolically’ with Black people is to refuse to actually do the work, and ultimately it reproduces the racism that disadvantages us. White people get to leave events feeling enriched (but often none the wiser) and self-congratulating for their progressiveness. Black people, on the other hand, are still faced with wage gaps, exploitation and poverty on top of emotional and intellectual fatigue.

Respectability politics will have us believe that to be deserving of simply existing as Black people, we must first educate white and non-Black people on how not to be racist. The work is presented as a choice between continuing in racism or choosing to teach non-Black people how not to be racist so that it would end. We know, though, that it is not that straightforward; if that is all it took, racism would have been eradicated by now. These opportunities present Black speakers, educators and artists another choice. “Who am I doing this for? That helps me decide if I want to engage in these initiatives,” says Mica. Who are your audiences at these Black History Month (or any other month) events? Will it help Black people, or will it help white people feel better about themselves while leaving you drained and uncompensated?

With all the resources that already exist for free on the internet, it is laziness on the part of anyone who refuses to seek it out and it is racism to consume Black trauma and labour for self-gratifying coming-of-age stories. So, I write this less to speak to non-Black people, and more to Black people like me, who have not always had the tools or language to understand the violence inherent in being asked to perform free labour to educate white people on racism. So, from this month forward, redirect them to the resources that exist. If they must have you educate them, set your fee. On Black History Month, triple it. If non-Black people and their institutions are committed to anti-racist practice, then let it begin with how they learn it.