*TW: homophobia, police brutality*

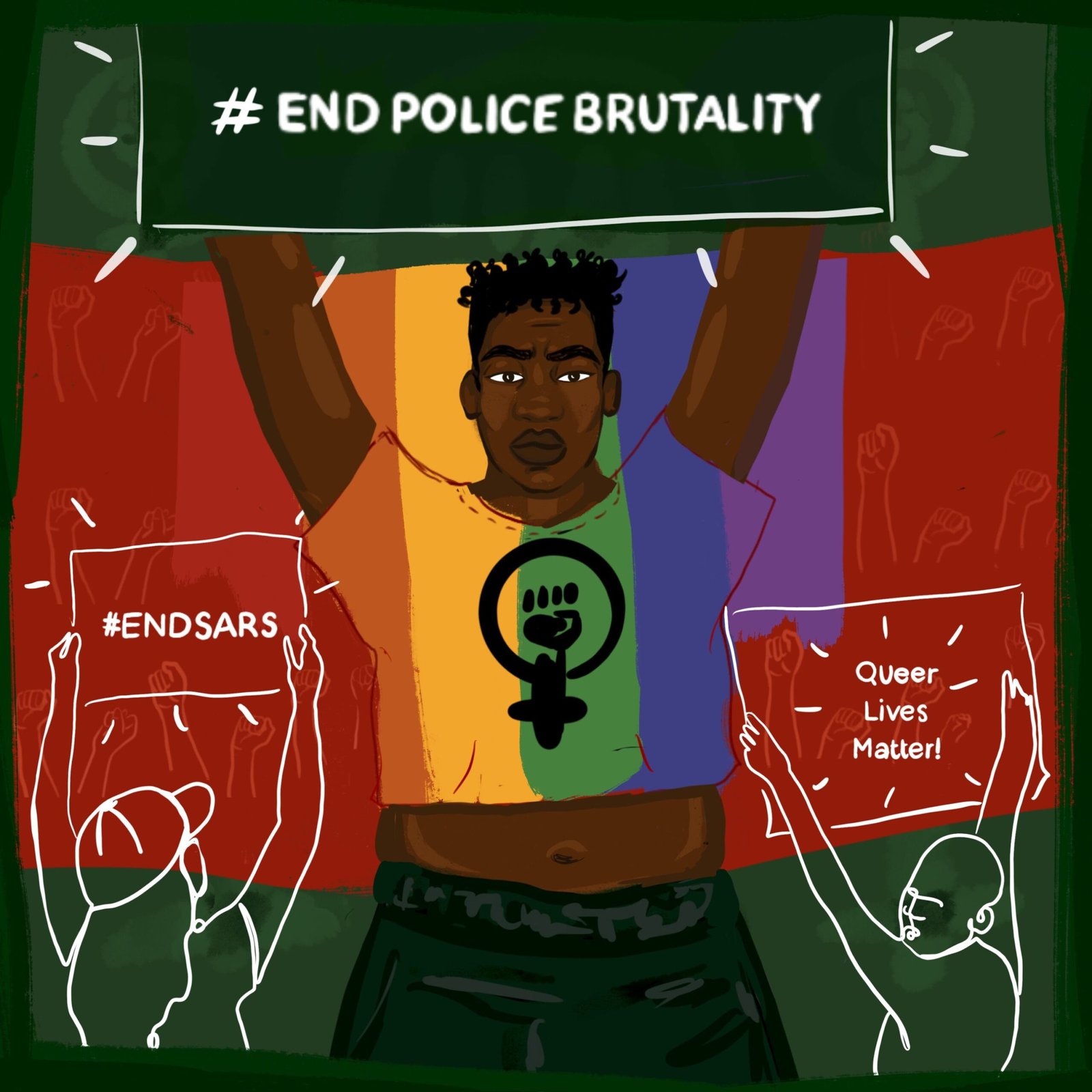

Matthew Blaise, a queer Nigerian LGBTQI+ activist on the frontline in Lagos, shares their powerful story of queer resistance in the face of police brutality.

“You’re stupid for telling us you have human rights, because here in Nigeria, human rights don’t exist. Other homos we arrest pay money and go – but you’re proving stubborn. You will be locked up in jail and nobody will know where you are’’. The policeman’s fingers twisted and pulled at my ear. His other hand kept a tight grip on a strand of my locs while the other policemen crowded me. All I could see was the black of their uniform, the ground, their boots and the extension of the AK47 he held. I squinted to keep the sweat out of my eyes. It didn’t work. I hoped I was dreaming. I knew it was not a dream. I tried to breathe slowly as the policemen pulled me towards their van for no reason. Well, they said they had a reason. I looked gay. This was the first time.

The conversation around police brutality has been present online in Nigeria for a while. However, stories of queer Nigerians are continually sidelined because Nigeria is a highly religious and homophobic country with laws in place to erase queer folks. Hence, queer people are seen as non entities. Our lives and safety are subject to the whims of those that hold power – in this case, the police.

I am an out and proud gay Nigerian, but given the treatment that queer people undergo in this country, I have always prayed never to get involved with the police. This is because when queer Nigerians are brutalised by the police, we are blamed for it. Instead of holding the government and its attack dogs, the police, accountable for the violence they inflict on the queer community, the culture of victim-blaming exonerates the government and blames queer people instead.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CGK580Bncvs/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Recently, I was picked up by the police again. I’m still processing it. I still can’t sleep without seeing their faces but I refuse to be silent. The Nigerian government is waging a war against queer Nigerians, and the police are its tools.

That day, I had planned a beach hangout with my friends. It was supposed to be a celebration of our ability to see each other, and a way to get my mind off the things that were bothering me. I had just come out to my brother and, although it could have gone worse, it could have gone better. I was trying to get away that hot afternoon when a police bus stopped and pulled me over. I became afraid. I am used to being afraid – fear is a collective feeling we queer folks in Nigeria have whenever we encounter men in black. As I got close, the first question I was asked was “why you dey do like woman and why you carry big yansh, you be homo?”(this means: why are you behaving like a woman and why do you have a big ass, are you gay?). I didn’t answer any of those questions because they were dehumanising and homophobic. One of the policemen dragged my bag and the other snatched my phone. They searched my bag for a moment, but couldn’t find anything incriminating. I thought that I would be released but instead, one of them gestured with his gun and pushed me into their van.

I asked where I was being taken but got no answer. There were possibilities in my head; maybe they were going to shoot me and abandon my body like they do to other gay people, maybe they wanted to get access to my funds to see how they could extort me. I thought about my future.

It is my dream to attend a colourful gay pride in Europe and even one day, in Nigeria.

I was jarred out of my thoughts when the bus stopped at the police station. Instead of taking me to the police counter, I was dragged to a corner where they had detained some boys who were caught with drugs. I realised later, that it was where the police carried out their illegal activities. They left me there for some time while they tried to extort money from the other boys who were illegally detained. After getting my phone, one of them came up to me to ridicule me. He called me “leaking ass”, “a community disgrace”, “a disappointment” and many other words that have become familiar to me. They reminded me of my family’s reaction when I was outed in a national newspaper in 2019. Since then, the harassment I’ve faced both online and in person has only multiplied.

The policeman handed my phone to me and told me to unlock it. I declined, and they became violent. They dragged me by my ear and hair. They kept making references to my body; about how “thick” it was and how they would throw me in jail where I would be “battered and sexually tortured by men” without anybody, even my family, knowing. They said all this without a face mask on, after having ripped mine off earlier. Though my country was relaxing quarantine restrictions at the time, it was not safe to be without a mask. They went out of their way to do every cruel thing they could think of.

It was a nightmare. Every time they spoke, they made references to my sexuality and the criminalisation of it. I was pushed into a chair and an officer sat across from me. He threw taunts at me with a smile on his face. There was a difference between me and the other boys. While they were subject to the whims of the police as well, they had some measure of protection under the law. I didn’t and he knew it. The Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (SSMPA), criminalises my existence.

The SSMPA fuels the hatred towards the LGBTQI+ community in Nigeria. Prior to its passing, queer people were targeted and ostracised. Our homes were burnt, our families ridiculed, jobs lost, and for some of us, lives lost. Despite all of this, there was a sense of hope because trends around the world showed a decline in homophobia. In 2013, the SSMPA changed that. With the criminalisation of homosexuality, the Nigerian government declared that the lives of queer Nigerians didn’t matter. They told us that we deserved to be locked up. They told us that we are less than human, because the basic human rights given to everyone do not apply to us. Before the SSMPA, Nigeria had penal codes that criminalised non-heterosexual activity, but they were passively upheld. The laws utilised ambiguous wording and prohibited sex “against the order of nature”, but did not specifically target gay people. The SSMP clearly outlaws the participation in, and officiation of, “same-sex” marriage. The SSMPA also explicitly bans LGBTQI+ organisations and penalises membership in them with a maximum sentence of 10 years in jail. Queer unions have a maximum sentence of 14 years.

So, as I sat there, across the table from a man empowered and legitimised by state sanctioned bigotry, I made a decision.

When the policeman asked me again to unlock my phone, I said no. I decided I was not going to bribe them, or deny that I was queer: all I was going to do was resist. I refused to open my phone, I refused to let them get my money. I thought I was going to die. I could have paid them, but suddenly I felt like everything depended on this moment and what I did. I realised arguing that I wasn’t gay would be participating in a life where the price for survival was self-denial. If I paid them, I would be contributing to the culture that allowed people to be relatively safe as a queer person in Nigeria only if they had money. Either way, it suggested my right to exist was up for negotiation.

I don’t know why, maybe they got tired and decided whatever money I could give them wasn’t worth the hassle I was giving them, or maybe I just got lucky, but they let me go.

I didn’t cry until I left the police station. Then, I went to the beach where my friends were waiting for me, and we danced.

Follow Matthew on their Instagram

See more of Tinuke’s work on her Instagram