Working in the Western music industry as an Indian presents its own particular set of issues. I’ve often found myself on the receiving end of comments that either talk down the genuine artistry in the Indian music scene or highlight only the increasingly popular trend of auto-tuned club remixes, which, although catchy, are drastically simplified versions of classic songs. But beyond this blinkered view of the Indian music industry lies a wealth of sometimes controversial, often layered and complex music that goes beyond the pseudo-EDM-like soundscapes and misogynistic lyricism that has become the ill-conceived emblem of Indian music.

With a recent surge of socially conscious, politically opinionated artists emerging from all corners of the country, protest music in India might seem like a modern movement. But the history of protest songs in India can be traced back to the pre-independence period. In fact, a poem (first publicly recited at the Indian National Congress in 1911) went on to become a symbol of patriotism as India emerged as an independent nation in 1947. The first stanza later became the national anthem of India, ‘Jana Gana Mana,’ originally composed in Bengali as Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata by polymath Rabindranath Tagore. A symbol for the nation’s commitment to its freedom and its diversity, this song embodies Indian dedication to secularism.

The power of music has continued to succeed in India where words have failed – or been deliberately silenced – in a culture where citizens’ rights to protest are curtailed.

In mid-April, as the election season enveloped parts of India, several Bengali artists came together just days before the first phase of polling in Bengal for a protest song promoting freedom of speech. ‘Nijeder Mawte Nijder Gaan,’ written by actor Anirban Bhattacharya, roughly translates to ‘our song from our point of view’ and seeks to push back against hate with unity. The viral hit featured national award winners Anupam Roy, Riddhi Sen, and Rupankar Bagchi as well as several prominent Bengali personalities.

Opening with powerful lyricism, “Our India is a country of diversity and love, one of unity. If hate and lies are cultivated then we must speak out,” the song vibrates with anger as it denounces othering terms such as “anti-national”. The lyrics instead call for attention to be directed towards the real issues plaguing the nation, including but not limited to fuel price hike, demonetisation, and the ongoing farmers’ strikes.

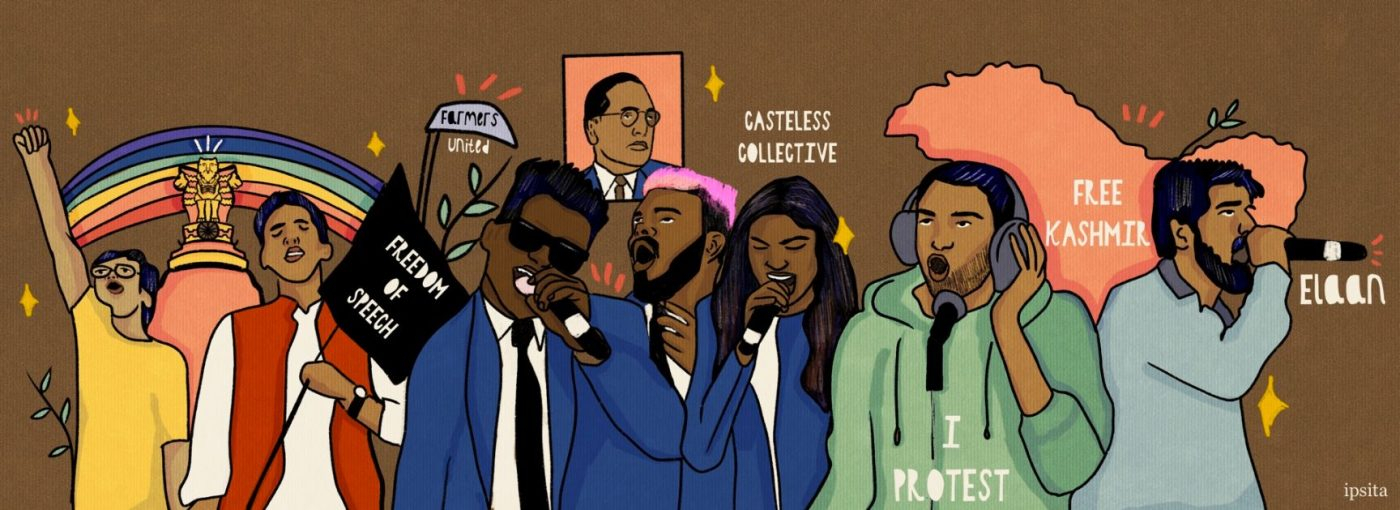

Where Bengal’s artistry highlighted the need for harmony and an end to monopolisation of patriotism, Kashmir’s political hip-hop movement was a living example of how a region’s volatility seeps into every aspect of human life. The movement slowly bloomed to life in 2010 amidst a prolonged civilian uprising in Kashmir, when Roushan Illahi, aka MC Kash, dropped I Protest, a no-holds barred, visually-traumatic remembrance for civilians killed during the insurrection.

Despite being created in an era where viral hits weren’t popularised on social media, the song spread far and wide. It served as an anthem for the youth fighting Indian police in the streets and catapulted MC Kash from obscurity into fame. Gaining a reputation as Kashmir’s revolutionary rapper, MC Kash went on to release several hits centred around the ongoing conflict in the region. His music inspired many others like SXR and Haze Kay to add their voices to Kashmir’s burgeoning hip hop scene. However, intimidation by the Indian government, financial constraints and lack of opportunities snuffed the flame that could have ignited the movement. In its place came a new wave of gangsta style rap which focused on misogynistic lyrics which did little to represent the struggles of peoples across Kashmir. This largely dominated airwaves of the 00s.

It wasn’t until nine years later in 2019 that the scene managed to reclaim its political agenda with ‘Elaan’, a song which delved into the lived experience of growing up in Kashmir. Featuring Ahmer Javed, who rapped in a mix of Kashmiri and Urdu, the song took Kashmir’s music across India ushering in an age of community-based hip hop focusing on sharing, learning and collaborating. With a newer spate of artists who better understand the nuances of politics in art, Kashmir’s protest music has begun to paint vivid pictures, darkened by brutal honesty and softened by artistic freedom. On“Tanaza – Conflict,” Ahmer’s collaboration with Tufail – one half of the duo SOS: Straight Outta Srinagar – was a marriage between poignant lyricism and cinematic visuals rooted in realism that tells the stories of corruption.

With catchy beats and confident vocal delivery, the electro-soundscapes of Indian protest music would not be out of place in any club. However, perhaps unbeknownst to clubbers are the stories the music tells, which bely the pain and trauma of the artists behind it. Lyrics narrate tales of loss, helplessness and righteous anger, in a protest space these tracks become fight songs thrumming with unity and humanity.

If certain parts of the country opt for powerful hip hop influenced sounds, others find expression in more stripped-back styles, such as those used by Tamil music project ‘Enjoy Enjami,’ which has taken the world by storm this year. Composed by Santhosh Narayanan and sung by Arivu and Dhee, the track is a transportive soundscape that takes listeners back into a much more harmonious, almost utopian, time in the world’s history where humanity stood strong above caste, race and gender. The track is a multi-genre experience which brings rap and folk together with the mourning artfulness of Oppari. An ancient form of expressing grief through music rooted in South Indian folk culture, oppari songs are a mixture of eulogy and lament typically sung by a group of women to mourn the loss of life. In his music Arivu uses this word-play rich art as a cry of resistance against the plight of landless labourers. Weaving tales with colourful idioms, Arivu, whose own grandmother was a migrant labourer, sings, ”I planted five trees/Nurtured a beautiful garden/My garden is flourishing/Yet my throat remains dry.”

Arivu, whose career reached its crucial turning point after becoming part of the band Casteless Collective, continues to tap into collective experiences and examples of historical defiance. From tracing the social oppression and caste hierarchies within the nation to dismantling the quota reservations imposed by upper castes Arivu and Casteless Collective build on real life stories of privilege and marginalisation to usher in a new era of protest music in India, that brings people together beyond boundaries of language.

There is no art without conflict, and there are no protests without anthems. What began as an ancient generation’s way of telling stories through song morphed into poetic assertion of the patriotic values of an oppressed country. Today these songs are shared symbols for the fight against injustice, cutting across various languages, genres and styles. These songs push against the merciless crackdowns of a fearful government against democracy. Where words are muted and actions are tied down, music fills the silence.

These anthems will be the motifs that lead generation after generation of protesters in India, journeying to an utopia free of oppression, injustice and inequality.

See more of Ipsita’s work on instagram