I feel like I am in a made-for-TV movie on my chain bus ride to prison. They call it a chain bus because all the riders are handcuffed and leg-ironed, connected by two chains which are pulled up around the waist with another locking the whole contraption together. There is just enough chain to bring my hands to my mouth if I bend over slightly – not ideal for eating or wiping my ass. When all 30 or so of us move about, it sounds like a bad symphony of cymbals clacking together.

Just me and the two prison bus drivers are white. I’m terrified, my guts are shaking like a vibrator pounding against my insides. But everyone aside from me is relaxed, chatting, as if they’re old friends catching up at a party.

“Man, this prison sucks. I was here in the 80s, they ain’t got no hustle going on,” one rider says.

“Yeah, but they’ve got lots of female guards,” another commented. Yells of “hell yeah!” follow.

None of this chat is directed at me. In fact, no one has uttered a word to me except the bus drivers who did so when they were chaining me up. I get up the nerve to ask my seat partner a question: “So, you’ve been to this prison we’re driving to before?”

Without looking at me, he stands up and screams out: “This white boy does talk. He better keep that mouth shut, cause soon he’ll have a big Black dick in it.” That comment causes a chorus of laughter like I’ve only heard in a comedy club. Even the bus drivers have a chuckle.

I feel the blood rush to my face and the heat hit my cheeks. I’m going to hell.

Tennessee in the 60s

“Can I touch your hair?” Keesha asks me.

We’re in second grade, in the schoolyard. No one had ever asked me such a question. Was something wrong with my hair that it needed examining? Keesha was the first Black girl I was this close to.

Growing up in Tennessee in the 60s, life was full of racial firsts. Neighbourhoods and apartment buildings began to be more diversified, mostly because Clarksville was a large dwelling for military personnel at Fort Campbell Army Base. Downtown shops where I used to see only white patrons now had Black customers. Schools became integrated, and the people I had always been taught to believe were the “others” were now my schoolmates. Some, like Keesha, were my closest friends.

It was never clearly stated in my childhood home that Black people were not equal with whites. But it characterised the undertones of conversations that chipped away at the level playing field. My family was already at the bottom. I never had a new set of clothes or a new pair of shoes until I went to work aged fifteen. One of my first purchases was a new pair of off-brand sneakers and stiff new blue jeans from the co-op store.

But however low folks viewed us to be, apparently there was a social and ethnic class that was lower than poor white trash.

In a visit to Tennessee in the 1960s, after encountering displays of blatant racism, President Lyndon B. Johnson famously made the comment: “If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best coloured man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.”

This sentiment was patterned by my small town. Just because the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination based on race, the local courthouse still had “White Only” painted on the wall behind the water fountain. Across the hall and down the stairs to the basement, a second fountain had been removed, but the painted words “Colored Only” remained there, clear as day. And I never saw any person that wasn’t white drinking out of that fountain.

My lightbulb moment

There were two permanent features at the lone pump gas station in town: Mr Lewis and Mr Dudley, two men stinking of chewing tobacco and stale coffee who, between them, didn’t have a pot to piss in. While putting some air in my bicycle tires one day, a car pulled up, a much nicer one than we were used to seeing in those parts, polished up like it had been on exhibit, with a young Black man driving. “Fill ‘er up, kind sir,” he instructed the attendant.

Mr Lewis and Mr Dudley immediately started up conversation, loudly pondering on where the man had stolen the car from. These two men, who lived in a shack on the edge of town, who ate raccoon stew and shit in an outhouse, felt superior to a person they didn’t even know, just because he was Black.

Kids are basically mixed up marionettes, being pulled and tugged in the direction of the other puppets. There is a point in time, however, that a kid sees or hears something that makes him uncomfortable; something is not right. Overhearing these men spewing such ridiculous assumptions and hateful remarks made a light go on in my brain and helped me realise how crazy their sentiments were. That’s when I began to acknowledge and question racist behaviour that I heard from then on.

What keeps a child from withdrawing his consent to the herd’s behaviour? Some things come to mind: family rejection, not fitting in, looking ridiculous, and ultimately, not being loved.

Mom and Dad are racists?

We were driving into the parking lot at the church one Sunday in our old Chevy. I’m not sure what colour it was originally, but it was mostly rust looking then. I loved it, I could spit on the street through the hole in the floor while in the backseat. This was all fun and games until it was raining, then I would have to put a grocery sack over the hole to keep the water from splashing up.

The breeze coming in the window blew the scent of Aqua Net hairspray around the car. Momma sprayed it like she was killing ants in her hair each Sunday after she teased it up real good. She always said, “Higher the hair, closer to God.” After all that work on getting it up high, she pinned a navy blue hat right on top, which squished it down a bit. God apparently didn’t like ladies bare-headed.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

As we approached the sanctuary, my brother Bubba and I would always get the same lecture from Momma: “Don’t let me have to tell you boys to hush up or be still. And don’t turn around in the pew and stare at people singin’. Cause if I have to, I’ll tan your hides when we get home.” Just then, Daddy noticed a new car, not one of the regulars, pulling up behind us.

“Betty Jean, is that a n***** lady in the car behind us?”

I turned to peek out the back window to see a Black lady wearing a yellow hat driving up behind us. By the time we got parked, the Deacon had approached the woman and informed her, “Your people’s church is down the road about two miles. Go on now, before you’re late for service.” She was the only Black person I ever saw on our church grounds.

“Good Ol’ Boys” stick together

My childhood taught me that Black people did not share the same privileges as white people. As a child I figured that must be the way it was meant to be. My community folk choreographed my existence into a dance of white privilege.

In my college years in Tennessee, 1979-1983, I found more nuanced forms of racial divide. We had mixed classes, and some words became politically and socially unacceptable to say out loud. I was experiencing cultures and accents that were intriguing and fascinating, not scary and dangerous.

The good ol’ Tennessee boys stuck together, with Jack Daniels, rebel flags, and racist slang shared with peers. But I gravitated towards a different clique of people, with a broader base of political ideas, and a community more accepting of people who weren’t white. But I still didn’t stand up to the people using racial slurs – I couldn’t push back, for fear of becoming a social pariah. I just slipped away through the side door, so I could still be accepted in the good ol’ Southern boy network if need be.

Prison stinks – literally!

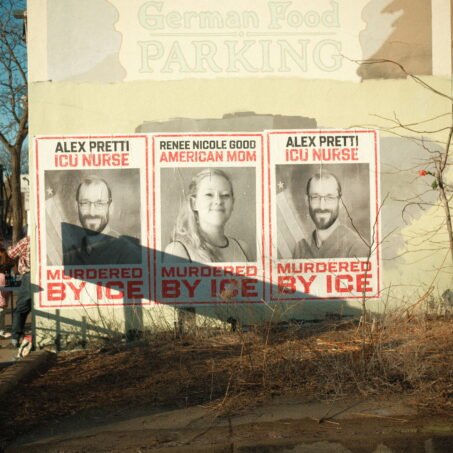

In the US, Black people are jailed up to six times the rate of white residents. Prison population is racially representative of racism in the infrastructure of the US – racist housing, racist policing, racist sentencing, and so on. The power structure in prison isn’t a reversal of power, but a continued consequence of unchecked white privilege outside the prison. This fact was materialised as I walked into my first prison cell.

My cell is upstairs. When I first walk in, the unit is chaotic and so loud I can’t distinguish words, only a concussion of noise. When others notice me, silence falls. I could hear a pin drop. The dominoes and cards stop being slammed on the table and the chatter is hushed. All eyes are on me, but I say nothing in fear of a repeat of the interaction on the bus.

“Fresh white meat,” are the first words to break the silence, and they come from a tall, built, older Black man. I say nothing and keep walking. Someone behind me grabs my ass. I jump, and laughter breaks out. My face becomes flushed with embarrassment and fear. “Save that ass for me, boy,” the ass-grabber yells. I pick up my pace to my cell.

I open Cell 215. The other person assigned is not here. The TV is blasting, a cigarette is burning on top of an opened Coke can. There’s bunk beds, the bottom one has sheets shuffled about, the top bunk has a thin bare mat. The metal shelves are full of crap except one empty cubby – that must be mine.

I find the bedsheet the prison staff gave me and put it over the plastic mat. It’s stained and reeks of cigarette smoke and urine. I take out my few bottles of state issued items: soap, deodorant, toothpaste, and put them on the shelf. Roaches scurry about, trying to get out of my way.

My first cellie was a neo-Nazi

A thin white man rushes in. “Thank God, you’re white,” he says in a thick Southern accent. I learn his name is Slick. “You must be in for one of those white collar crimes, cause you talk all proper,” he smirks.

“Murder,” I tell him.

“Oh shit, I’d never guess that,” Slick says. “This place is full of n******, so you better click up or get ready to fight every day.”

He sounds like my old peer group from high school and college; the groups I walked away from years ago. I had evolved, educated myself, and grew more accepting of different races and cultures. I had left Clarksville, the city of my birth, and hadn’t looked back. But I was still in Tennessee, and at this moment I suddenly feel like a little boy once again. The one that is now beholden to this racist man in front of me who shares my prison cell.

“You ain’t a queer are you?” Slick asks. “Have to ask, cause the Brotherhood can’t cell with no queers.”

As sickened as I am am by the realisation that he’s in a neo-Nazi gang — on top of the brazen homophobia — I’m ashamed to say that at this moment, with Slick, the racist man whose racist world I recognise, I realise that I’m relatively safe – as long as he doesn’t find out that I’m gay.

I shake my head. Slick smiles.

“I can talk to Tank about getting you clicked up with the Brothers.”

Slick brings me up to speed on the culture of the prison: “You’re white, not tatted up, clean looking, not a druggy, so you’re prime meat. You have three choices, fight, fuck, or check in.” ‘Checking in’ is where you go into protective custody, and are generally locked down in your cell for 23 hours a day.

Slick tells me about the Black gangs in the prison. “You got the Bloods, the G’s, the Vice-Lords and the Memphis Mafia. If you violate their space, you’ll get charged. If you don’t pay, you’ll get beat up or killed.”

Now I’m in position to get charged for violating a Black space, like back at the courthouse in Clarksville, where “bad things” happened to the Blacks who dared to drink out of the “white only” water fountain.

The sheet hanging from the vent around my neck is looking like a better option than those Slick has just laid out for me.

Gangs control the prison

Waking up in prison is an awkward experience. Navigating the small space with another grown man, we move around peeing, washing our faces and brushing our teeth. On that first morning, look at the window and see the guard opening only a few of the cell doors – all belonging to Black guys.

Slick explains that the Black gang members, because they are in a majority and have the most influence, get out first to get ice, shower, pass dope about, and warm up their coffee in the microwave After that, the guard will let the rest of us out.

I notice that the warden at this prison comes around occasionally inspecting the unit. He always makes time to stop by the gang leader’s cell to chit chat about life and what their needs are. If they are happy, then the compound remains relatively safe. If the gangs rob, assault, deal drugs, a blind eye is turned very often. Because if the inmates are only hurting each other and not the prison staff, the administration takes that as a win.

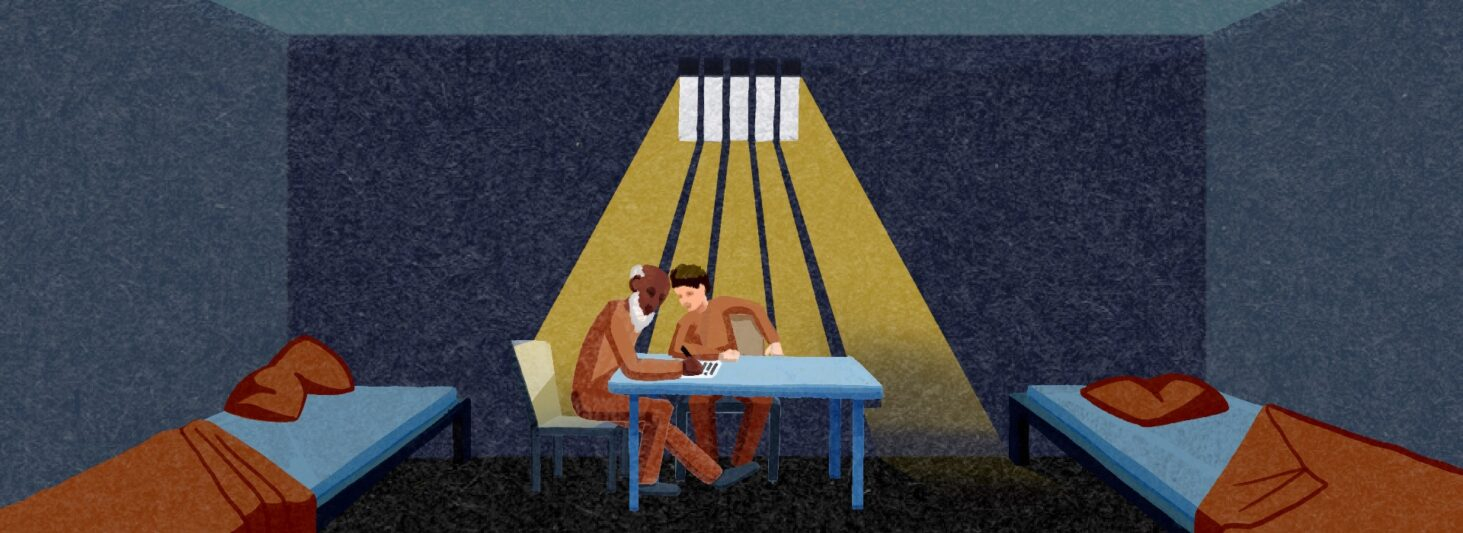

So how did I avoid all this? After a few years in the system, I found the prison’s “Switzerland.” Randal was an 6’5” oldhead, in for 25 years already, a thug on the street but not in a gang. Somehow he had gained respect from both the Black and white gangs.

When he discovered that I was educated, he asked for my help in writing. Attached to him, I was left alone by the gangs – and everyone else. His friendship allowed me to get close to gang members and have real conversations. Taking the time to listen to people’s stories that didn’t look like me opened my heart to new friends and relationships that I would not have experienced otherwise. When you know about someone else’s life, you are less likely to harm them and them you.

What 30 years in prison has taught me

After being in prison for almost 30 years, I’ve learned a few things.

In the 60s, if the people at my all-white church would have taken the time to invite that Black lady in the yellow hat inside the sanctuary to worship along with us, we may have learned that she was wanting a place to sing and praise the same God we were celebrating.

If I had asked Keesha why she was so intrigued with my hair, I may have learned that she was as amazed by my whiteness as I was of her Blackness, and the differences of skin colour have little to do with the basic desires and needs we all have.

In prison, I can no longer slide in and out of a racist culture like I did at college. I realise now that it’s because, back then, none of the comments or actions were against me.

Living in a small bubble of existence creates extremist levels of prejudice and causes harm to those that are different or “fewer than.”

People do not want to be alone, especially in prison. It’s easy to fall into a Black or white group – whichever looks like you. Instead of spending time on convincing those that look like us that are better than those that don’t, why not stroll over and say, “Hi, I’m Tony, who are you?” Injustice largely depends on those around remaining silent. It took being in a minority for the first time in my life to make me realise that fully.

Most of my friends these days are Black. We’ve formed book clubs, writing groups, attended classes together, laughed and cried together like brothers. It seems we all want pretty much the same thing: to be loved and accepted for who we are.

What can you do?

Read:

- The New Jim Crow

- White Fragility

- Never Surrender

- Secrets from a Prison Cell (written by the author)

- Locked In and Locked Out (written by the author)

- More shado articles from incarcerated writers:

Volunteer:

- This story was supported by Empowerment Avenue, a collective that supports incarcerated writers, and is always looking for volunteers with writing backgrounds – just email empowermentave@gmail.com

Contact:

- You can reach out to Tony Vick via the mailing address below. (Do not use address labels or stickers, and only use white envelopes and black or blue ink.)

Tony Vick #276187

SCCF

PO Box 279

Clifton, TN 38425

United States

- You can financially support him through JPAY (Tony Vick / #276187 / Tennessee Department of Corrections).