British transphobia deploys its violence throughout the mainstream press and with feminist arguments to lend it credibility. However disguised, the arguments are by now familiar for their repeated obsession with protecting ‘womanhood’. One the one hand, we are told that trans women are predatory men who must be policed for the safety of other, more “real” women. And on the other, we hear that trans men are women whose transition to escape femininity marks them as vulnerable, foolish, or traitors to the cause. JK Rowling famously expounded this exact stance in both her (in)famous blog post and numerous times on Twitter. In both cases, the boundaries of womanhood form a battleground for debating the very existence of trans genders.

Meanwhile, (cis) men don’t seem at all fussed. There are no billboards telling transmasculine folk to stay away from manhood, no campaigns to rescue trans femmes from their transition. This silence follows a general erasure in men’s spaces that stretches beyond sexual/gender diversity, and represents a failure to seriously address the narrow, fragile boundaries of masculinities. There are surely some very valuable questions to ask about the psychosocial reasons for this. But more urgent are the political consequences of excluding transmasculine people as valuable members in the brotherhood of men.

Limitations of the “men’s movement”

Conversations about masculinity continue to swarm our public consciousness, boosted most recently since the murders of Sabrina Nessa and Sarah Everard. These conversations are in part developed by the men’s movement – a collection of individuals and organisations working in research, policy, education, and the arts. Broadly speaking, its aims are to unpick the “toxic” aspects of masculinities and reform them towards a more progressive model. The movement’s relationship with feminist, anti-racist, disability, and anti-capitalist activism varies. But universally, it remains ignorant of trans masculinities and approaches its project from a thoroughly cisgender standpoint.

An easy example is Movember, the movement’s most successful campaign towards men’s physical and mental health. Raising £34.5million in 2020 UK alone, and having a cultural impact far beyond this, the campaign’s entrance policy is clear: whether or not you can grow a moustache. This aligns with and reinforces an almost comically shallow standard of masculinity that equates it with facial hair: if you wanna be a bro, you gotta grow a mo.

This supremely exclusionary standard reflects Movember’s limited understanding of “men’s health” as primarily involving male biology, through illnesses such as prostate and testicular cancer. Their work on suicide prevention makes no mention of trans people, who are uniquely at risk from it. A site search for even the most general term “transgender” found 0 results. And so, a campaign that promises so much ends up repeating the ‘boy’s club’ code that welcomes only a very particular form of (cis)masculinity.

Real outcomes for trans and cis people

The primary casualty is of course trans men and other transmasculine people, who are vulnerable to extreme persecution but are totally ignored by the movement. When the NHS quietly stops providing bottom surgery to trans men, no men’s health activists get active. When the state refuses to legally recognise trans fathers on their child’s birth certificate, fatherhood campaigns are silent. When classrooms of young boys are educated on “healthy” masculinities, there is practically no mention of transmasculinities. Presumably these issues are considered niche or more properly the business of LGBTQI+ organisations, if they are considered at all. But the end result is the same: transmasculine people receive no support from the men’s movement for the medical, legal, and social deprivation they experience.

Cis men too are neglected by a movement that fails to connect them with their trans brothers. A central part of many ‘healthy masculinities’ campaigns is encouraging men to build intimate, mutual relationships with each other. But these campaigns are defective if they don’t work to connect men across the cis-trans binary. Without bridging this gap, cis men are deprived of the opportunity for friendship, joy, and mutual understanding with transmasc folk. In turn, this too often prevents them acting in solidarity and support with transmascs, something that is crucial for the spiritual betterment of individual cis men, and masculinity as a whole. Only once cis and trans people share openly in the similarity and difference of their masculinities can the rigid boundaries of masculinity begin to be prised open.

The erasure of transmasculinities

Erasing transmasculine folk from the men’s movement is a failure on all counts. At best, it limits the scope of campaigns; at worst sees them operate through exclusion and ignorance. It does further harm to already marginalised transmascs, stripping them of brotherly solidarity and support. And it prevents cis men building this brotherhood, which is ultimately in their own interest. Overall, erasing transmasculinity perpetuates the exclusionary masculinity that plagues transmasc folk today, and upholds the very systems of privilege and oppression that a men’s movement should be seeking to undo.

It isn’t trans guys’ job to save cis men, nor are trans guys exempt from toxicity. And it isn’t my place as a trans fem to speak on behalf of transmasculinities, except to point out their exclusion. Cis men and the movement that supports them must work to engage transmasc people in finding out what they need, and how to help. Numerous such people and organisations already make outstanding contributions to trans liberation both in and beyond transmasculinity. I’ve linked to a few below. As ever, the job for those wanting to work with and deconstruct their privilege is to put down the master’s tools, step outside the master’s house, and join those working outside.

Transmasculine Campaigns

Gratitude again to Audre Lorde, whose work on difference, solidarity, and The Master’s Tools continues to inspire mine.

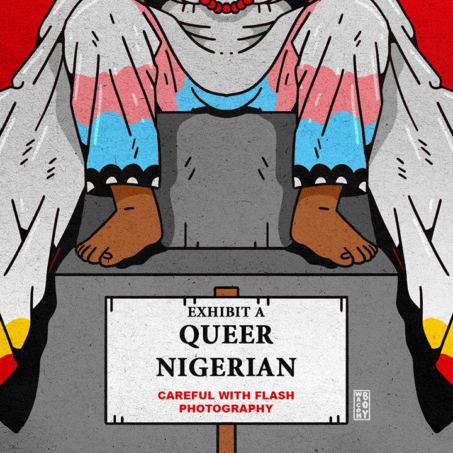

In the image the artist wanted to show how the rigid societal rules of masculinity really do a disservice to men and their ability to connect with struggles and even their own liberation. The artist wanted to create an abstract piece that shows that no one benefits from the constraints of masculinity and that indeed there are so many ways that it can be embodied and it is queer people have been shaping what that can look like.