Last November saw the sixth edition of ART X Lagos. The fair brings together artists from all over Africa and its diaspora to showcase their works at Nigeria’s Federal Palace Hotel in Lagos. ART X Lagos serves as a place of artistic resistance and resilience, with its artists creating work around the theme: ‘the restful ones are not yet born.’

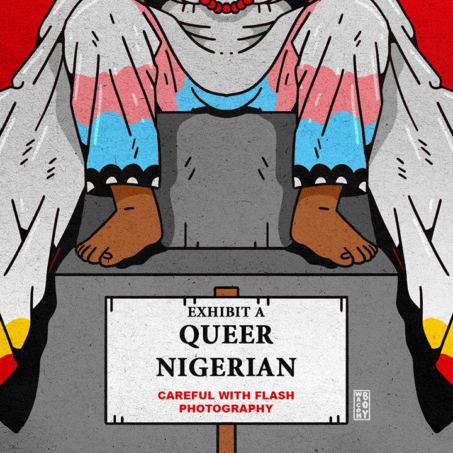

The theme is apt. As citizens in Nigeria, we cannot yet afford to rest. This is because colonial influence in Nigeria still disrupts our society; with patriarchal nationalists at the helm of the government, we are resisting constant attacks on women’s rights, queer existence and the exacerbation of poverty and class divide.

Where oppression and injustice exist, marginalised groups are often expected to maintain their positions; to not resist or push back. When these groups can and do speak outside of the boundaries set for them and claim space in the dominant discourse, they cause discomfort to those upholding these structures.

I define activism simply as a refusal to maintain the status quo. By that definition, artists who use their medium to speak out are activists themselves. I spoke to three such artists at ART X Lagos.

Zethu Matebeni, a South African queer feminist, activist and scholar, reminds us that art can be a valuable and necessary form of protest when resisting marginalisation and discrimination. It is all the more important when you look at the Western art scene’s history of dominance, which has traditionally weaponised the power of art by misrepresenting and marginalising African cultures.

The first piece by Côte d’Ivorian artist, Roméo Mivekannin that I sawwas ‘Le Nègre à L’éventail’ [The Negro with a Fan], 2019. As a queer scholar, I initially saw this as queer – as I do most things. I immediately read into it the discomfort of a naked man with a fabulous fan, posed so elegantly.

It took speaking to the gallery representative from Galerie Cécil Fakhoury to recognise that the piece was, in fact, not necessarily intended to be queer – but instead this work spoke to Western art and its legacy of depicting non-Western people without agency.

I was immediately confronted with the problem Mivekannin was illustrating. I saw his display of self-representation and agency through my own perspective of queerness, and in doing so, exposed my position and robbed him of his. Recognising this was my point of discomfort as a viewer.

Considering how the West has always represented non-Western people, it is easy to see the non-Western subject as objectified and passive. Mivekannin resists these historical depictions of Black people. In Danseuses marocaines La danse aux mouchoirs, Mivekannin reinserts himself into the classic painting by Théodore Chassériau of the same name. He places himself as the subject, and by doing so, creates ‘copies’ of Western paintings, transforming them into a series of self-portraits as a means of self-representation. Here, with the agency to present himself and tell his narrative, he challenges the idea that non-Western people cannot represent themselves.

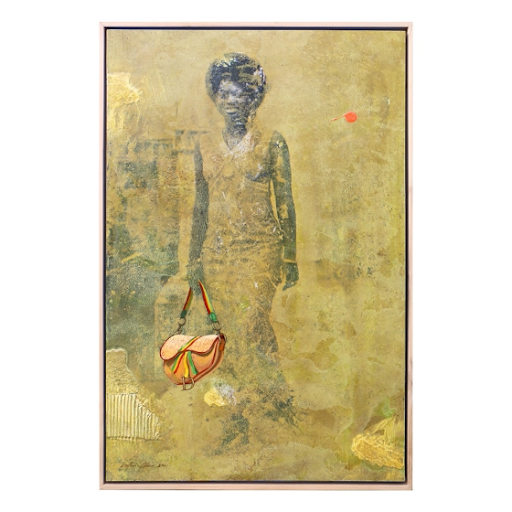

Mona Taha’s pieces, presented by Afriart Gallery, were the first to catch my eye as I arrived at ART X. Taha is an artist from Kampala, Uganda and her work, to me, is an embodiment of defiance and empowerment. With a degree in development economics and a history working in logistics, Taha defied her family and societal expectations to become a full-time artist. For Taha, the pieces are “very personal.” She tells me, “they centre around female empowerment; feminism is a strong theme in my work.” This instantly places Taha’s work in the realm of art activism, and it is a categorisation she relates to and embodies throughout her work.

Taha believes we exist in a culture where a woman is expected to be “a Good Girl [the title of her artwork]”. A culture where a woman is expected to be “silent and doesn’t give much of her opinion.” Her work is about “having the courage to put yourself first” and representing how you choose to be seen. In her self-portraits, Taha has agency: she uses her art as a medium through which to tell her story and she refuses to be quiet.

I couldn’t help but also read queerness in Taha’s ‘Good Girl’, with its display of sex, sexuality and desire. Taha agrees with this, saying, “you can’t talk about feminism without talking about sexuality and having the freedom to be yourself.” This is a crucial piece that still evokes discomfort for many in Nigeria considering the multiple laws that mark female and LGBTQI+ existences with state-sanctioned discrimination and violence. By presenting ‘Good Girl’, Taha shares a tender moment that resists the status quo in this space and time in Nigeria.

Photo by Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi

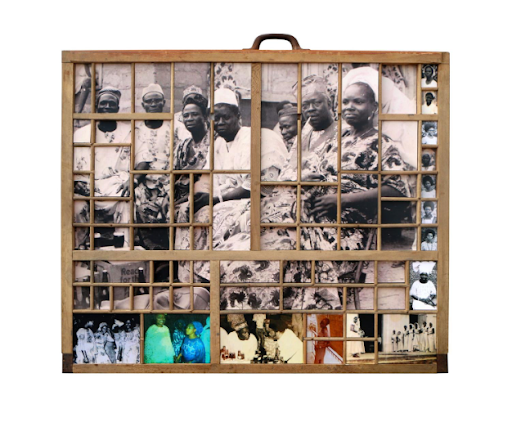

Kelani Abass, a Nigerian artist, also looks at the role of women through his work. Their piece “Unfolding Layers of Time” looks at the different roles women have taken throughout history. Each picture highlights that women were present during specific eras in history. Abass reminds us that: “in the past, if you look at politics in Africa, they created no space for women.” He believes this makes it easy to erase women from history. By focusing on the role they played, he also highlights that it’s time to see what women can do in politics.

Through ‘Fading Vanity’, Kelani also speaks to how accumulation of power and wealth plagues Nigerian political ambition. He explains that this is futile and leads to further marginalisation for some members of society. Kelani exhibits fading, sepia-toned photographs of poised, fashionably dressed people, whose designer possessions have been painted over in bright colours. This simultaneously speaks to how some things never change – despite the time that has passed, we still exist in an era where Nigerian society is preoccupied with consumerism – but material possessions will come to lose value over time.

This exposes the nuance and complexity in his works. As Abass says, “we like materiality. We like to accumulate, and we can’t take that away from women, either.” This spoke to me as a critique of representation politics and the complexities of women’s inclusion in politics. It is also a critique of capitalism and the consumerist culture that plagues our society. By highlighting women’s participation in these systems, he illustrates how simply having women in power won’t be enough if there isn’t a critical analysis of capitalist systems and our attitudes towards the consumption and power-hungriness that guides Nigerian politics.

Abass’ works highlight a significant issue in Nigeria. Alongside the sustained consequences of our colonial history and the marginalisation of various identity groups, we are forced to confront the reality that the positions of power expected to bring the necessary changes have become a place for purposeful apathy, corruption and wealth accumulation amid intense poverty, police brutality and discrimination. We are forced to confront the need for a transnational and intersectional struggle that not only fights for representation but critically assesses the systems we are fighting so hard to be a part of.

“The restful ones are not yet born”, and it is clear that discomfort is necessary. We cannot rest. Many artists embodied this through their works at ART X Lagos. By delving into critical points of activism in Africa, they explore self-representation from the shackles of colonialism and orientalism; women empowerment and feminism, including queer politics; the erasure of women participation from history; the pitfalls of representation, and an interrogation of the accumulation of wealth and power. They explore our complexity and present us as beings with a convoluted history and an imaginative future.