On 1st May, 2024 a group of so-called counter-protestors attacked the pro-Palestine student encampment at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). This was one of over 200 protest encampments across the United States in what has now come to be known as the “Student Intifada.”

The attack lasted 3-4 hours before any police or university intervention. Several witnesses state that though police did arrive early on, they stood aside as the violence continued with one security officer claiming that this “was the pro-Palestine protestor’s fault.”

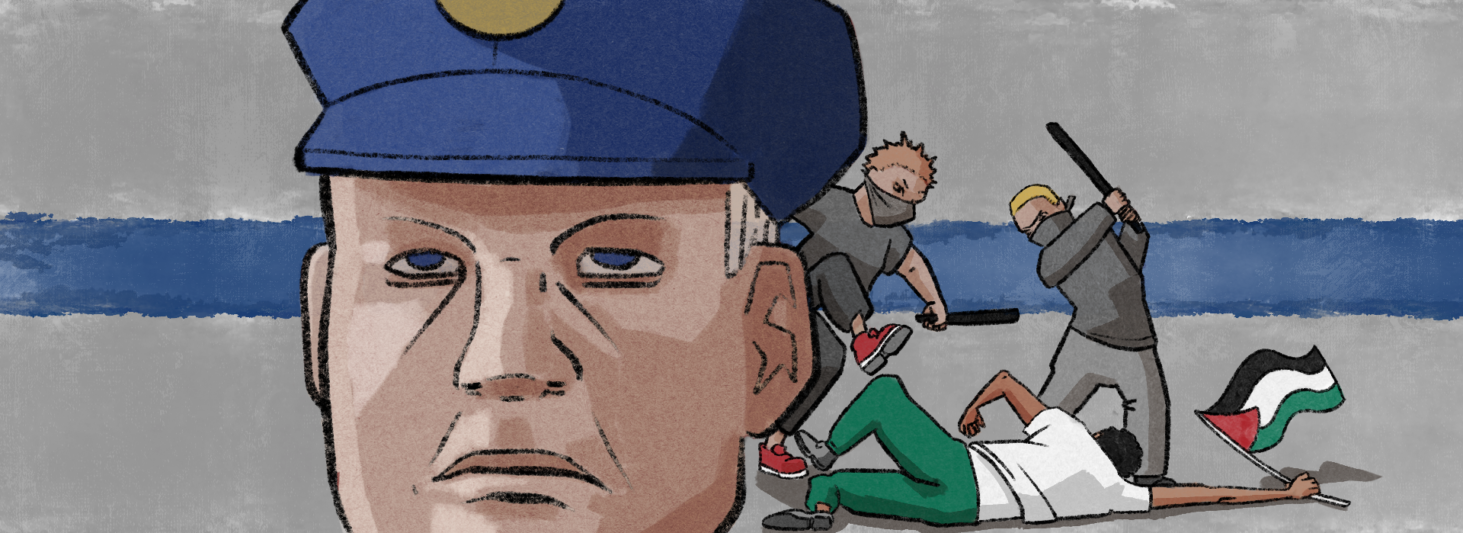

The strategic and targeted violence that unfolded at the scene that Wednesday morning, along with the evident impunity with which the violence took place, exposes the same type of classic deniable atrocities carried out by urban paramilitaries from the dirty war era up to the current date in Mexico.

As a professor and author of political economy and geopolitics, I have spent the last 25 years of my life investigating, and documenting historical and contemporary acts of military and paramilitary violence in Mexico and their direct connection to US military and intelligence intervention in Mexico.

The CIA’s Dirty War in Mexico

In 1947, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) assisted Mexico in the creation of the Federal Security Directorate (DFS) as part of the Truman Doctrine.

The DFS was extremely effective in quelling insurgencies and social movements during what is now known as the Dirty War era by committing state-sponsored crimes against humanity and atrocities such as massacres, torture, kidnapping, and targeted assassinations.

The Dirty War in Mexico officially lasted from 1964 to 1987. Independent researchers declare that it lasted from 1954 to 2000. I would argue that it began with the formation of the DFS in 1947, and has never ended. What has changed over time is who exactly is presented as the official enemy, and who is used to confront said enemy.

In the late 1940s Mexico already had in place the beginnings of a counterintelligence program within higher education institutions in Mexico City. By the 1950s, this strategy spread throughout universities in Mexico City such as the National Autonomous University (UNAM).

One key strategy is known as porrismo (urban paramilitarism) and is still in place today.

A porro is a paid and protected student or non-student thug, who belongs to an organisation much like a syndicate with other porros, functioning particularly within a public education framework. They are compensated in various ways for carrying out acts of violence against student organisers, specifically at protests. They can generally be associated with right-wing conservative political alliances within Mexico’s political parties. These associations are in addition to providing payment for services, also provide protection from prosecution or sanctions from the university administration.

The word in Spanish for “cheer” is porra, hence the root of the name. Porros are organised, violent cheerleaders for political, economic, and military interests within educational institutions throughout Mexico. Porros are one of the roots of paramilitarism in Mexico, and serve as a model of militarised counterintelligence and counterinsurgency against the general student body. Porros have functioned and continue to function in Mexico with impunity to this day.

Defining paramilitarism

One could reasonably argue that the hyper militarised police we see around the world today are a form of paramilitarism. Within the Mexican context however, militarised police or the actual military carrying out police duties, has now pretty much become the norm.

There is nothing new about militarised police forces, not just in Mexico or around the world, but throughout the United States as well. However, paramilitarism as experienced in Mexico has specific functions, strategies, roots and intentions. It is this type of paramilitarism that we are beginning to see more of in the USA as well.

Paramilitary forces are armed civilians who receive training, support, and financing, or simply receive protection from official entities such as a political party, a government administration, the police, or the military. A paramilitary organisation may also be generated and supported by non-governmental institutions like corporations, banks, or individuals such as local land barons, or the political elite as well. Paramilitaries use violence to carry out social, political or economic objectives against a target civilian population that is either considered a disposable variable, a barrier, or a direct threat to a given political, economic, or military interest.

The primary purpose and function of paramilitarism is to generate and exploit what are known as deniable atrocities. That is to say, its purpose is to carry out obscene acts such as threats and acts of violence, extrajudicial executions, kidnappings, beatings, rape, and torture against a civilian population in such a way that governments, police, or the military can deny involvement in and/or responsibility for those atrocities once committed. These atrocities are used to dissuade social, political, or economic opposition.

A key calling card of paramilitarism is that the agents carry out their atrocities with total impunity. It is impunity of this nature that further delegitimises governments and their justice systems altogether.

When a paramilitary group is generated from a local population to cause internal conflict in a target region, oftentimes ideological, political, religious, cultural, geographic, or social differences between opposing groups are exploited to generate violent confrontations.

A common end result of the “deniable atrocities” carried out by heavily armed paramilitaries around the world is the further official militarisation, policing, and criminalisation of the community, organisation, group, or individual being targeted.

1968 Student Massacre

By the late 1960s, various porro organisations were active. In 1998, declassified CIA documents exposed a working relationship between Mexican PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) government officials beginning in 1947. This relationship evolved steadily and in 1960, under the auspices of a CIA agent by the name of Winston Scott, the CIA began a programme named LITEMPO.

The programme entailed the creation of an untraceable covert communication and coordination apparatus between the CIA and top Mexican officials including the Mexican president Diaz Ordaz himself, and the Secretary of the Interior Echeverría Álvarez as well.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

On 2nd October 1968, ongoing tensions erupted between the Mexican government and leftist student organisations engaged in a massive protest in Mexico City. The protest ended in a bloodbath at the hands of infiltrated provocateurs and the Mexican Army itself under direct orders by the Diaz Ordaz presidential administration, through the Secretary of the Interior Echeverría Álvarez. Both of them would later be identified as on the CIA payroll through the LITEMPO program.

The infiltrated provocateurs, some of whom were identified as soldiers of the Army, opened fire at the scene and the military responded by firing as well. Both fired into the crowd. The official death toll was 300, but witnesses claim hundreds more were murdered and disappeared. None of the soldiers involved in the massacre were ever charged with a crime.

Less than two years later on 4th May 1970, the US Army National Guard would open fire on peaceful protestors at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, killing four, injuring nine, and paralysing one. Though soldiers responsible for the Kent State massacre were tried, not one was ever charged.

1999 UNAM Student Strike

On 20th April, 1999 at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), the University Student Assembly (AEU) became the General Strike Council (CGH), and the UNAM entered into an enormous system-wide general strike, which lasted 11 months. The 300,000+ student university system came to a grinding halt. The primary goal of the CGH was to stop a near 500% tuition increase at the institution. However, among the list of demands by the CGH was also:

“The dismantling of the apparatus of repression and espionage created by university authorities as well as the ceasing of violent acts or sanctions against teachers, students, and workers who participate in the movement.”

In 1999, UNAM students were still dealing with porros. The porro strategy during the student strike was two-fold. On the one hand, porros would carry out various acts of violence against student protesters, and on the other they would also carry out acts of sabotage in order to erode popular support for the student strike. The students at the 1999 UNAM strike had already dealt with porros in their daily student life. Therefore they would follow disciplined protocols for engaging in civil disobedience.

For students who participated in the general strike, acts of plunder, theft, holding people captive, mutiny, injuring others and damaging university assets would only serve to delegitimise the student movement and justify repression. These acts were consistently committed by porros and not by student organisers.

Over time the acts of violence and sabotage carried out by porros would greatly contribute to the popular support for police intervention to end the general strike, in particular among the mainstream media. Hundreds would be arrested. Strike leaders were identified, isolated, tortured and charged, while all others were simply forced to sign blank confessions in order to be granted their freedom.

Towards the end of the 1999 UNAM strike I had the opportunity to travel to Mexico city to meet strike organisers and get to know the autonomous zones they had created throughout the university. Inspired by the 1994 Zapatista National Liberation Army´s Indigenous uprising in the southeastern Mexican state of Chiapas, the UNAM students decided that in addition to their permanent protest encampment, they would need to experiment with building actual autonomy.

In order to confront the porros, students organised security patrols with a central communications centre. They occupied meeting halls, built a student cafeteria, built a student clinic, took control of printing presses and launched an unlicensed community radio station.

For me this would be the very beginning of my understanding of the importance of self-determination, self defence, and autonomy to liberatory social movements. It would be these same UNAM students who would later invite me to the states of Oaxaca and Chiapas to learn about social movements and the militarism and paramilitarism they would confront.

Back to UCLA and the American Dirty War

What was witnessed at UCLA in May this year can easily be associated with the Mexican dirty war strategy of porrismo, first and foremost because of the level of documented impunity granted to the violent attackers by the university and the police. It is this impunity that exposes a clear relationship between supposed fringe counter-protestors and university and police authorities. We do not have any footage of the police or military standing by during a porro attack in Mexico since the early 1970´s. As a result attacks have become extremely violent and even deadly in the coming decades.

Though several mainstream media outlets and concerned individuals on social media have begun to actively expose the identities of the UCLA attackers, none have been arrested or faced any charges. It is this type of impunity that emboldens these types of acts of violence.

However, Pro-Palestine protestors, at UCLA in particular, but also across the USA, have been arrested and charged with a variety of violations as well as suspended and expelled from their universities. The strategy worked in exactly the same way.

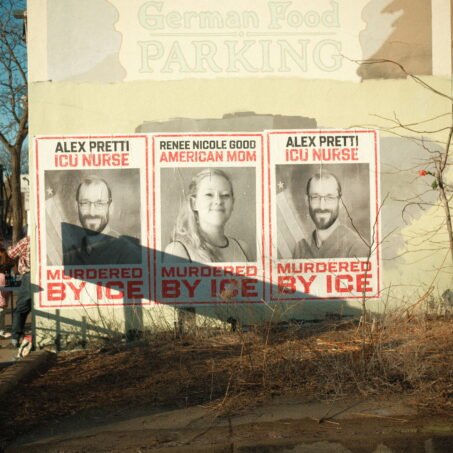

The UCLA attackers, coupled with other violent paramilitary style attacks against protestors during the 2020 George Floyd uprising against police violence across the US, which included the unpunished murder of two protestors by an under-aged armed vigilante by the name of Kyle Rittenhouse in Kenosha, Wisconsin USA does beg the question: Exactly how long before we can officially declare an American Dirty War Era?

What can you do?

Read:

- On Paramilitarism, Disappearances, Fascism, and Civil War

- Kenosha, Wisconsin: The Calling Cards of Fascist Paramilitarism

- LITEMPO CIA eyes on Tlatelolco Massacre LITEMPO: The CIA’s Eyes on Tlatelolco

- Kate Doyle & Jesse Franzblau, Official Report Released on Mexico’s “Dirty War”

- More shado articles on Palestine

Watch: