shado first met the brilliant sisters Enas and Alaa Satir in December when the revolts erupted in Sudan – find out more here. Four months later and the revolution is still ongoing. Both artists, Enas and Alaa are based in Toronto and Khartoum respectively, and while both of their work differs in content and style, they share a position at the helm of the current movement of protest art that has been used as a tool of resistance, education and awareness-raising within Sudan and the diaspora.

shado interviewed Enas and Alaa to find out more about their motivations, aims and processes as artists and the role they have each been playing within the current revolts.

We have been following the work that both of you have been creating in reaction to the protests in Sudan since December. What have your main aims and motivations been in the art you have been creating?

Enas: In part, it is to build momentum and keep it going…momentum can easily die with the lack of support. Whether you are inside of Sudan and you are protesting, or you are outside of Sudan and are sharing the news on social media, or talking to other people; artists who can contribute their art – it’s just a way of contributing, and to show support through whatever it is that you do.

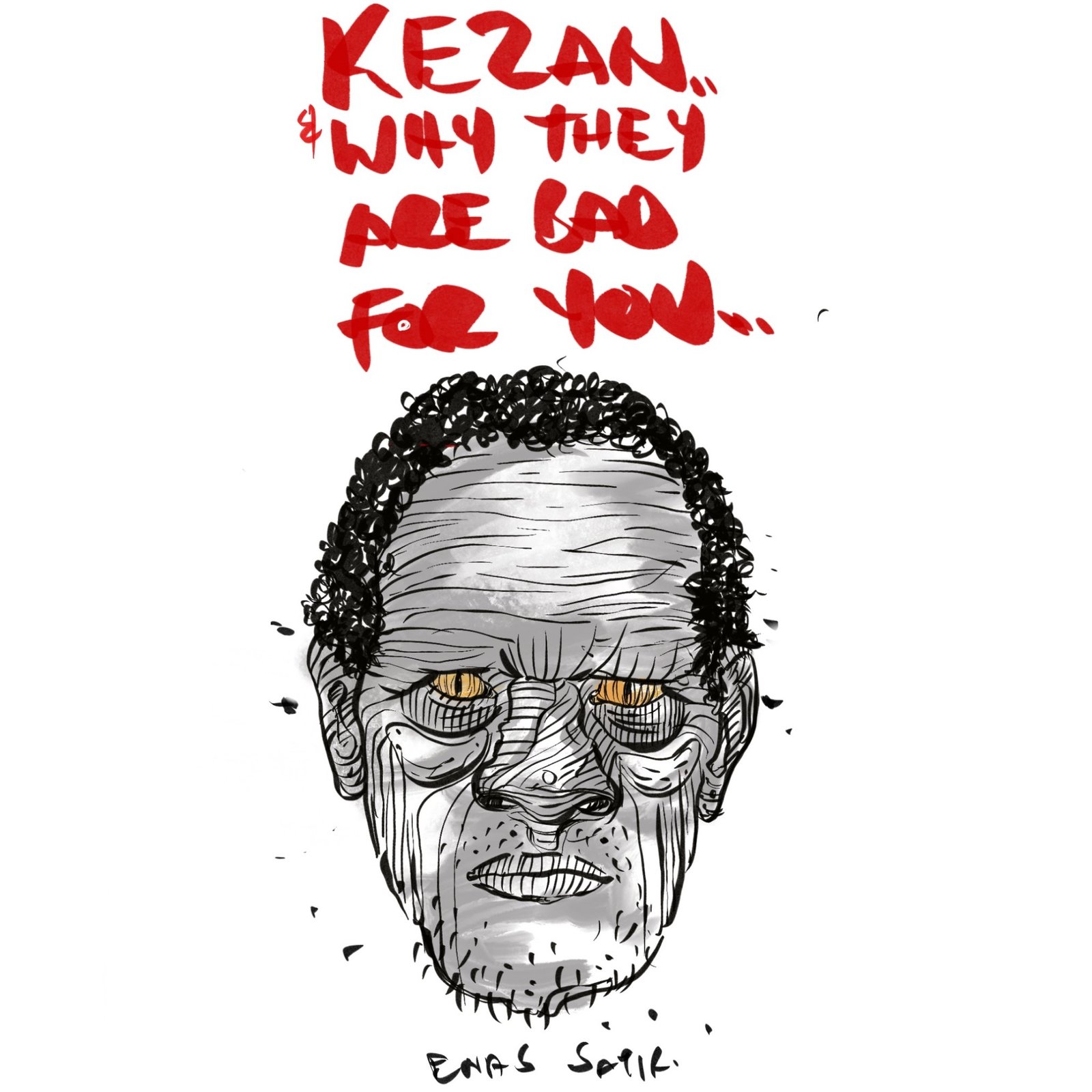

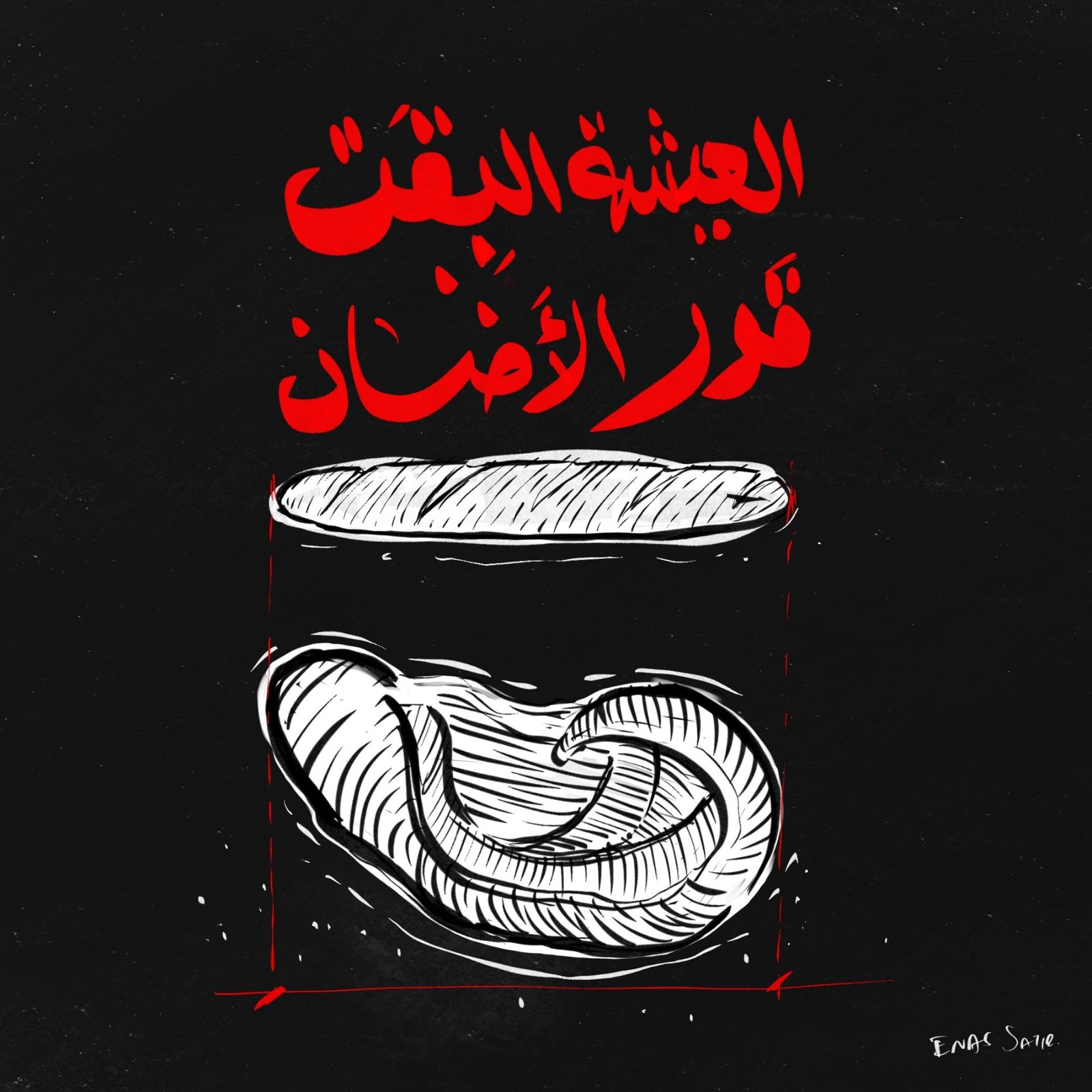

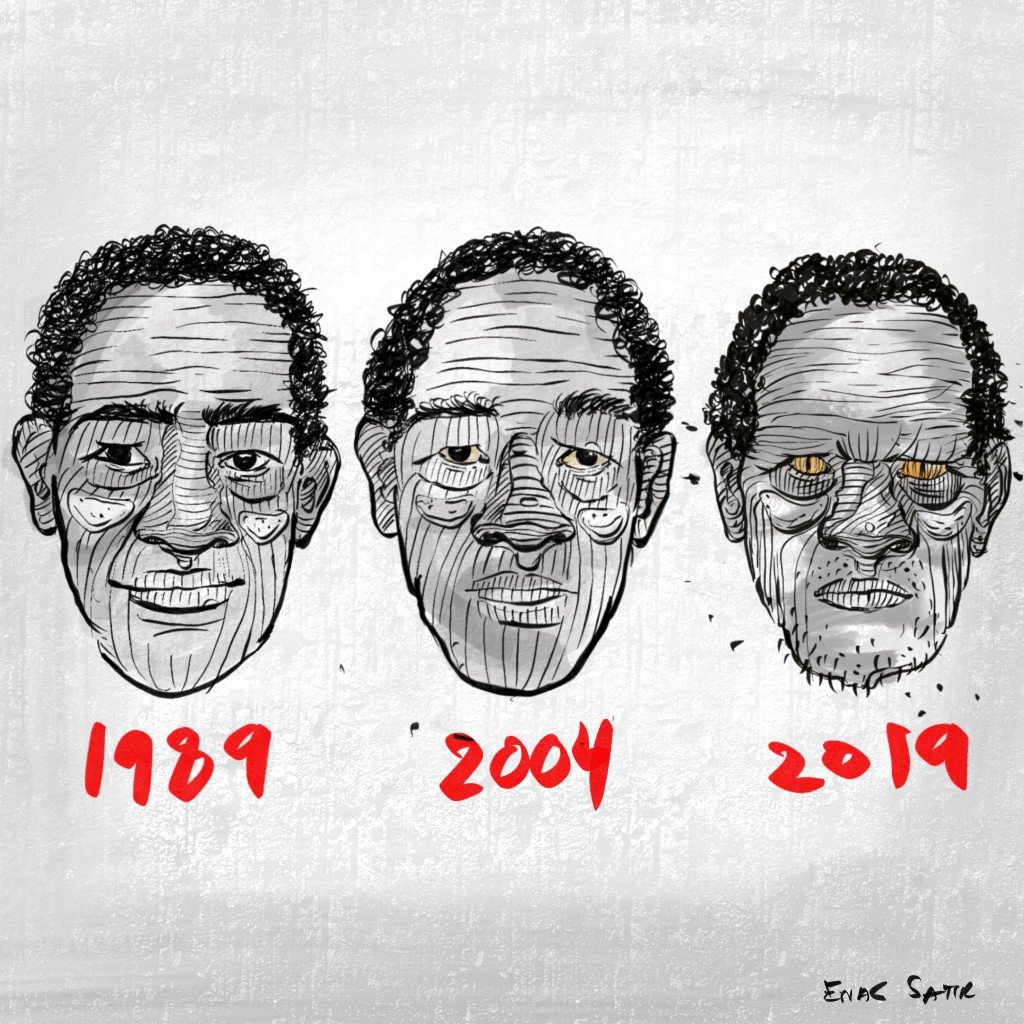

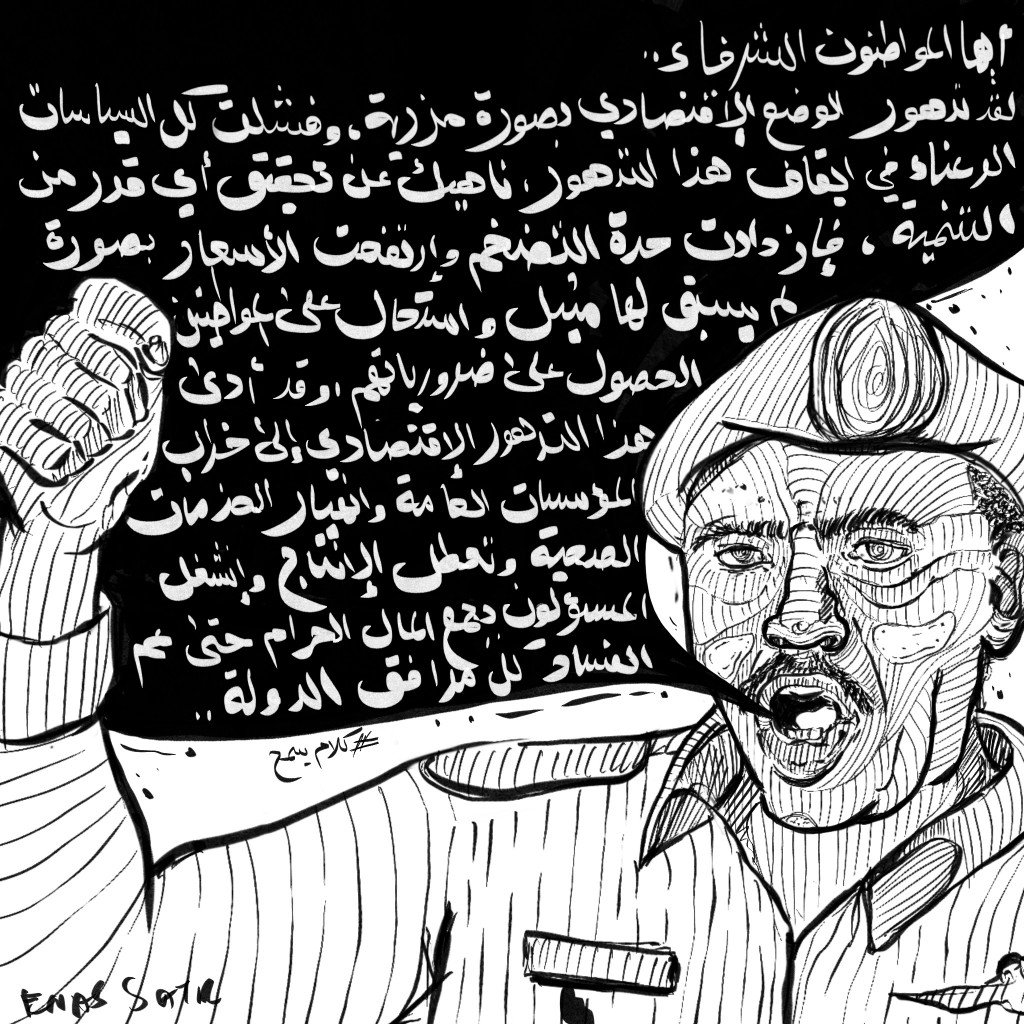

My work is not always focused on Kezan, but this first series is, because it needs to act as an introductory series. Especially when it came to non-Sudanese, I needed to explain what was happening in Sudan and I can’t do that without explaining who the Kezan are and how the current events came into play.

In fact, I don’t think we should focus on the Kezan at all. We have so many things we need to focus on in our society that may otherwise remain unfixed, even after the Kezan leave – we can’t blame all the problems in Sudan on the Kezan or whoever is in power, and this is the jist of my upcoming work as well.

This first series was supposed to be something somewhat light, to just show the general idea behind why people are protesting, instead of just thinking that all of the protests are because of the economic crisis, or be shrugged off as a bread revolution. I wanted to show that there are other reasons that do not all concern the economic situation or the bread shortages.

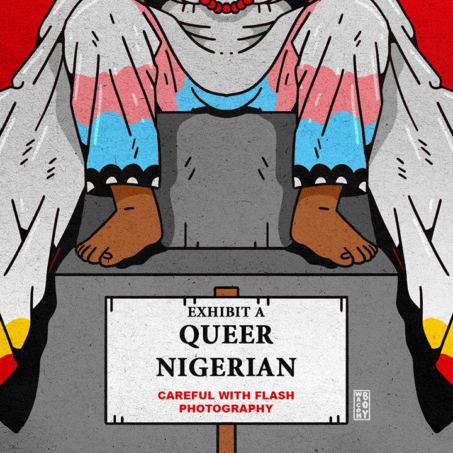

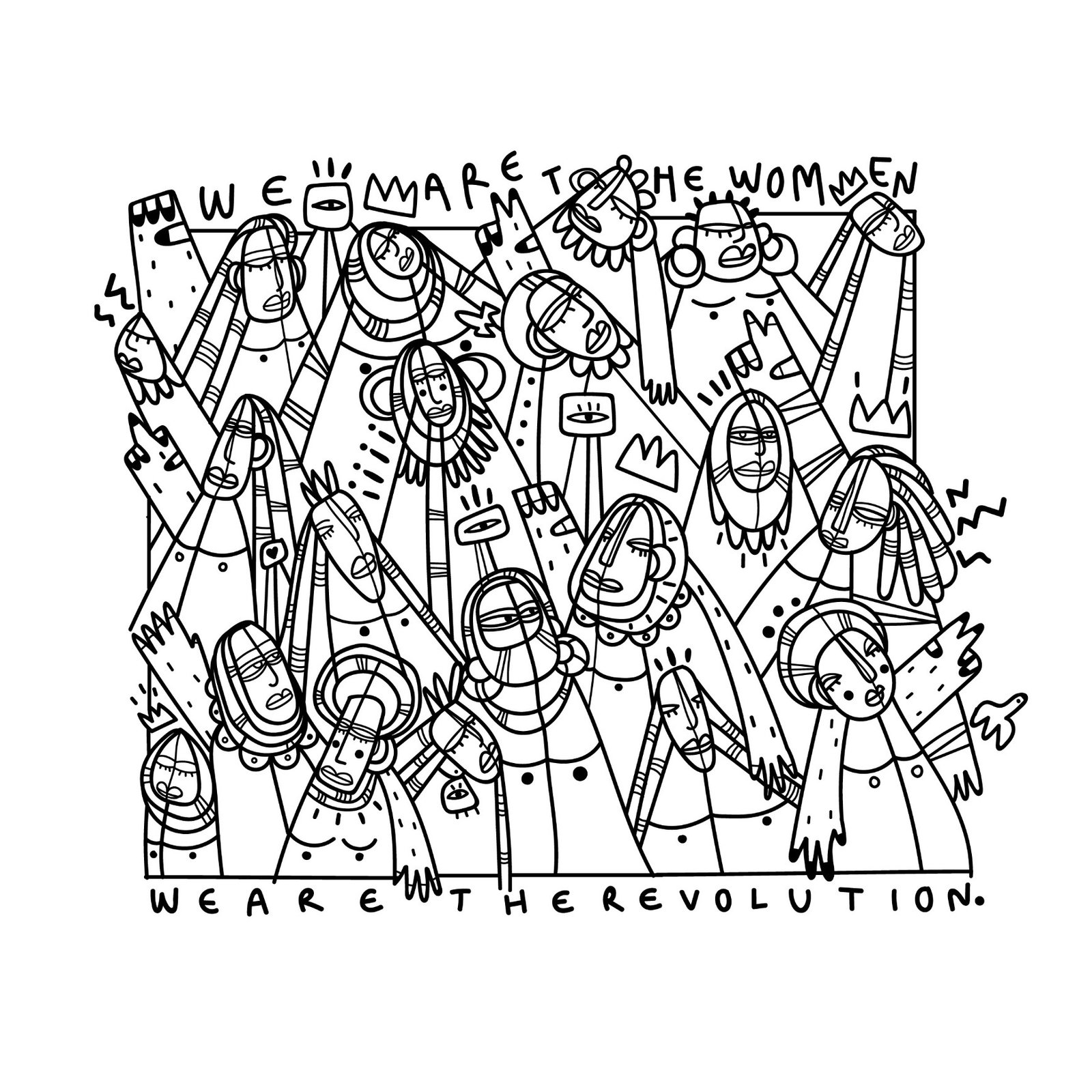

Alaa: I’d say that women have been a huge source of inspiration to me. To see them on the frontline of these protests – it was inspiring, but not surprising at all, because I believe that as women we are born to fight. It’s in our blood: we have been in this battle for freedom and equality for a very long time now, and when you see a regime that has been alive and well for 30 years that has hurt women the most, that has oppressed women the most, and people are out there trying to take it down – it’s not surprising to see that most of the crowds out there are women. It’s also a reminder that we’re not only trying to take a political regime down – we’re also trying to take a social system down with it; the ideas that we adopted from that regime, that were there to bring us down as women. So our fight for equality and freedom started way before the uprising, and it was important to me to remind people of that. It was also important to document the uprising from a woman’s perspective, since we are the casualties of that regime. We were the people who were harmed the most; we were the people who were harassed the most.

Why do you think illustration is such an important contribution to the revolts and as a means of outreach and advocacy?

Enas: Simply because when you draw or illustrate something, the eye will catch it faster than a written word. In an article, you can take your time and explain things.. but the artwork is what’s gonna stick to your mind, and it’s more intriguing to people – they may want to know the meaning behind it, or the motivation behind it. Thankfully, art still holds a certain status in our communities; it is valued and appreciated, therefore it more widely circulated.

Alaa: I think that illustrations are just like any other form of art. Illustration is a way of documenting what is happening now;

it is a way to write history as we go.

It’s also a way to evoke emotions which will connect us more to the problem and to the cause, and that will inspire us to push even harder or to fight more. It’s also a way to grab people’s attention; people who are not in the middle of all of it. If they hear a song, or see a photograph, or an illustration, that will make them curious enough to know about what’s happening here in Sudan – and that is really important.

How have your own experiences influenced your work?

Enas: The pivotal point of all of my work is my experience; something that is unique to me.

There’s always this debate between imagination and authenticity. Creative people are always pushed to be imaginative, and how imaginative they can be is usually a measure of how “good” they are. Imagination is great.. but I rely more on authenticity. Authenticity is your own point of you that stems from your own experience. Your story is always gonna be different and unique to you.. sharing it with others will helps them to identify with you, because they are touched by something they know is true, and not a fraction of your imagination.

When I was younger I was more intrigued by writing that art. I actually believed I was going to be a writer. Every time that I would go to writing workshops, they would always ask me to write out of imagination. The further I can go with my imagination the better artist I would become.

I couldn’t disagree more.

I’d rather write about what I know best, and don’t just tell me “what happened”….I know what happened.. tell me what YOU THINK about what happened.

If you put aside the things that define you, or you think define you – being a feminist, an activist, an artist, whatever it is – and share something (art or otherwise) from the basis of you being a human first, as opposed to having it ingrained in your mind that “I am a feminist/artist so I need to talk and act like a feminist/artist”. Instead, I talk about me, being just me, Enas, and simply speak my mind and share my experience.

Speak your mind and tell your story – it’s really as simple as that.

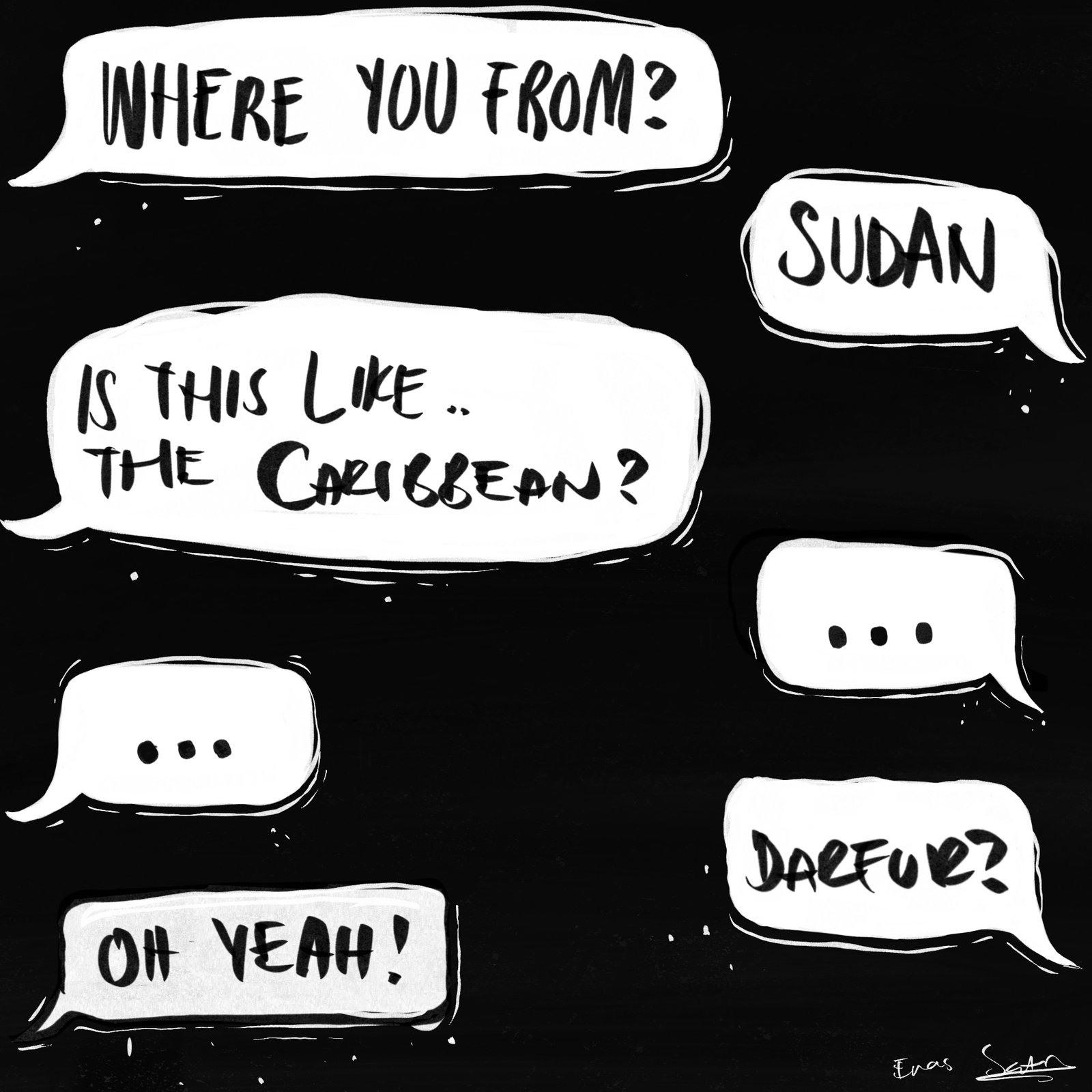

When I talked or made projects coming from being discriminated against due to my skin tone or my hair in my own country, being a woman, being Sudanese, being a Sudanese living in Toronto…all that is my experience and little snippets of my story, so a lot of my work revolves around that. My work usually has a point of view, so it is considered political, which fine, but it comes from true experience and incidents that shaped my life.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

I remember when I did Dominance, which was a project about the two identities of Sudan: the Afro/Arab identity. I felt that there was a huge difference between the Arab identity and the African identity. Something that was very obvious to me was that those with an Arab identity always had the privilege of being on the ‘Arab side’. Although they were officially black, because they were Arab, they didn’t feel that there was this huge divide – but, I felt it, because I’ve always had people commenting on my dark skin-tone in a negative way, or commenting on my hair, saying it is not “good hair”, that my skin-tone is “too dark.” And that I was “too African” to be Sudanese! I was once in Kassala Airport wanting to go back to Khartoum, the guy in the counter refused to let me get on the plane, because he insisted that I wasn’t Sudanese even though I was holding out my Sudanese passport and talking in plain Arabic to him. This is an experience, like many other experiences in my life that drive me to talk about discrimination, no matter what kind of discrimination it is. I cannot think of anything I have done, or written about, or drawn, or created in any way, that was not influenced by my experience. It is easy to be kind of general, and talk about “being black”, but there is a specific thing about being a Black Sudanese, or being a dark-skinned black, or a dark-skinned black with an afro.

Alaa: My work is actually just a way to document my experience:

living on this earth as a Sudanese, black woman living in a Muslim country, and hoping to god that people will connect with it

even if they don’t share the same environment that I inhabit. So, yes, it is not just influenced by my experiences – it is basically my experiences put into art.

How does your female Sudanese identity play into your work?

Enas: If you see any of my artwork, my writings, my “art”, you can see that I am always influenced by Sudan. Because Sudan is a big part of who I am and is a very complex country, with a complex culture, it’s not like any other culture. There are Arab complexities in it, and while this is beautiful, it is at the same time very challenging. So either I would be portraying the beautiful side of that, or I was portraying the difficult side of it. It has very much been an integral part in everything that I do, to the point that people often ask me to forget that I’m Sudanese and just try to do something different. But I always feel that I come back to being Sudanese, or at least very specific to Sudan.

I currently live in Toronto, but I’ve lived in Sudan for a big chunk of my life. Being a woman in Sudan, a place where people told me that I was supposed to act a certain way; I was supposed even to dress in certain ways,talk in a certain way, think in a certain way…you are packaged in the “good girl” package, and you better fit!

Of course, all of that shaped my personality, so this has also informed my work. My work, and writings, that is very much influenced by being a woman, and especially a woman in Sudan.

Alaa: I think Sudan is a very rich and complex culture that I find myself everyday trying to learn more about – so, it’s a very huge source of inspiration for me. As a woman, I think my work is basically me trying to present the everyday challenges that come with being a woman living in Sudan. Sometimes I even try to make fun of these challenges or mock them. I think this combination of being Sudanese and being a woman has influenced my practice a big deal.

How do you think your work is informed by where you are living (Enas in Toronto and Alaa in Khartoum)?

Enas: Take for example the latest Kezan zine I made. I doubt that, if I was living in Khartoum, that I would still come up with this zine. Like I say, everything that I do is specific to my experience and to my circumstances, and this is no different. The Kezan zine came out of the experience of living in Toronto, and being around people who didn’t know much about Sudan, and when I would tell them about the protests, they would kind of…not shrug it off, but sort of label it as a general thing, although there are a lot of things that are very specific to Sudan that make these protests different. Also, when I tell people that I am Sudanese, most of them don’t even know where that is. When I tell people specifically about Sudan, it is clear how little they know about it, because they just ask me very obvious questions…which shows that you really need to tell them even the basics of the basics. So, I have had a lot of conversations that I wouldn’t have had at home in Sudan, because of course, everyone at home knows those things. But, yeah, if I was in Khartoum, I wouldn’t make the Kezan zine, because nothing that I drew in it was something new for Sudanese people – but, it was particularly eye-opening for those who are not Sudanese. Here in Toronto, the reason I came up with it was because I was in a different society and I needed people to know a little bit about where I came from; what is going on; you know, to keep the conversation going.

Alaa: Yes, Khartoum has hugely influenced my work. It only makes sense that Khartoum would inform my work,

because this is the city that I know the most, the city of my people – so everything about Khartoum is sort of a source of inspiration for me.

The things that happen; the social issues; the political issues; the conversations I have; even the way that the streets look and the people look – how we dress, how we behave…everything about Khartoum is a source of inspiration to me.

Has your position online and on social media allowed you to mobilise different, diasporic audiences who are in support of the revolts?

Enas: Yes, very much so. Also, this is one of the reasons that Sudanese art has been so vital in this revolution, and in these protests, simply because the media has not been playing its part. This was especially true at the beginning, because now it has finally been gaining momentum –

but at the beginning, the reason that everyone was spreading the news on social media was because the media was not covering it, and what they did say did not cover it in enough detail or with enough clarity – which was very frustrating, and it made us feel like we needed to step in.

Then, I feel like everyone put in all of their efforts, and all of their resources, into trying to communicate what was going on in Sudan. When I share something on my social media, most of my friends, after seeing it, will ask me what is going on. They would like to know more, and with the media, they don’t get the same picture. So, I feel like

social media has been very active, and that it has been very crucial in all of this, because we are communicating real stories that the media doesn’t have time for

or maybe we have different agendas. Whatever the reason is, it was more covered on social media than it has on regular news outlets. Also, it has to do with my living outside of Sudan. When you live inside of Sudan, everyone knows what is going on, but outside of Sudan, most people don’t know. This is because they have their other lives, and that the news has been occupied by [supposedly] ‘bigger’ crises, because of course they have a marketing agenda as well. Whatever the reason is, people do not know about what is going on, so in order to get the news out of Sudan, it is very crucial to use social media. In Sudan, everyone knows, for example, today there is a protest and this many people died – it’s not as important to spread the word inside Sudan. The main thing is making people outside more knowledgeable about what is going on.

Alaa: I think we are lucky to live in this era of social media. It was really nice to see that people were reaching out, trying to know more about the uprising and what is happening, because of a story that I shared or a post that I posted on social media. It’s a great time to be an artist, because I don’t know how I’d be able to reach so many people if I used traditional media or newspapers or exhibitions. Now,

social media helps to lift these barriers between people

and it helps also to make room for information to flow easily. That really benefits not only me personally, and my work, but it’s also benefiting the uprising.

There has been a huge outpouring of protest art in Sudan and the diaspora. Who, or what, are some of your influences?

Enas: The answer, first, is Alaa. Not just because she is my sister – her art has been very inspiring, and very different. Also, Dar Al Naim – her work is great. A lot of Sudanese people have been great. I feel like the revolution has created more artists: a lot of people have been sitting up and working hard to put the messages out there.

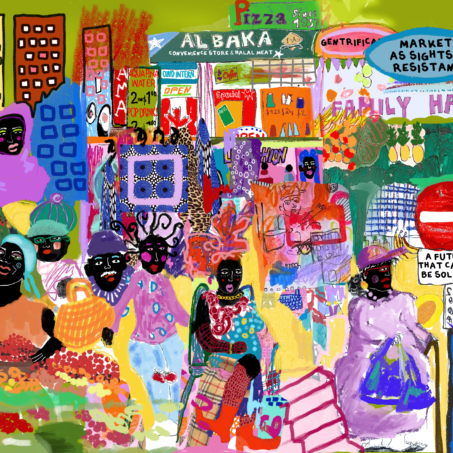

Alaa: It was really inspiring to see different artists mobilising their talent to help and advocate for the uprising. I see a new artwork every day, from either artists that I know or artists that I have got to know during the uprising. To mention a few of the artists that I like, I’ll say that the design that Enas created that was called ‘Kezan and why they are bad for you’ – I thought that this was a very important piece of art, because not many people are familiar with Sudanese political history. Even some of us, as Sudanese people, are not very familiar with the political history of Sudan, because they do not teach us that at schools, so if you know anything you know it because you wanted to. So, it was really a nice piece of information, put in a very attractive and artistic layout, that I really enjoyed seeing. Also, there are a couple of music tracks I like. One, I don’t know the artist behind, but the other one is by Sammany Hajo. He’s a young musician who took tracks that were circulating during the uprising, and mashed them together in this musical piece that was really emotional to listen to. It was something that I really enjoyed.

You have both been central to the situation in Sudan, but are there other issues that you feel strongly about representing and supporting in your work?

Enas: I have a lot of topics that I would like to talk about, because most of my work is surrounding feminism, and also racism and discrimination in general.. especially when I was younger in Sudan and these topics were not talked about. Discrimination against people with dark skin was not talked about, nor was the discrimination that would exist against girls with kinky hair. This argument was not brought up before. Even at the time I started talking about it, people would look at me, or talk to me, as if I was just being bitter about it; as if I was jealous that I didn’t have the ‘right’ sort of skin-tone. It’s not that this was something that I wanted to aspire to:

it’s that I am calling out an injustice

and the way that people think or talk. Definitely, now, more people have become aware of it, because of a lot of art projects that have been happening on the topic of dominance, and people have been more vocal. For the younger generation, it has been much more open and liberal, and people have been much more aware of what is going on and more fearless about discussing it. So, I feel like these issues which have been very important to me are being addressed by the younger generation.

It’s funny that you ask this question, because last month, there were lots of people posting pictures of themselves with a white Sudanese Toub (traditional dress), to kind of symbolise the Sudanese woman. There is someone – his name is Ahmed Umar – he posted a picture of himself wearing this Sudanese Toub, posing as a woman, wearing makeup, with hair extensions in, and he took the time to explain all of these traditions, and why this movement is great, talking about the protests and all of that, and people had a serious issue with him posing as a woman. Of course, it shows a great deal of homophobia, which I know exists greatly, because people who come from Sudan often don’t understand that homosexuality isn’t a disease, or against God – so, it just showed me that people could be open to women rights; they could be open to Africanism; but made me wonder if this is as far as they would go!

We still have a long way to go when it comes to the rights of gays. This is something that is a difficult argument, because anything that involves religion and sex becomes a very contentious topic, and people are unlikely to want to talk about it. They shut it down with the reason that it is mentioned in the Qur’an or so. So, yeah, this is one of the things that made me feel like we really have a long way to go, and that this should be addressed more, but at the same time it takes a lot of courage for people to talk about things like that: to talk about the red lines of sex and homosexuality when you have been raised to believe that they are wrong. At the end of the day, when you are protesting for freedom, you need to understand that freedom means freedom for everyone – not just freedom for you, or for people who look like you, or act like you, or dress like you, or think like you. It includes freedom for people who look different from you; who have a different point of view. The backlash on Ahmed made me feel that we really have a long way to go. So, yeah, I’ve always liked to talk about these sorts of topics, and also other topics that are very personal to me, such as mental health – the way that the issue of homosexuality gets tied up with religion, it is the same way with mental illness. People think that being depressed is no different from being sad, and that the reason you are depressed is because you are not practicing your religion right: you’re not praying, or you’re not reading the Qur’an often enough. Mental illness has nothing to do with that.. it is a medical condition, and it ruins people’s life and not out of choice, or lack of discipline like most people think.

I haven’t yet been addressing these issues as often as I would like, because I know they are sensitive topics, and how they will be received depend very much on how I approach them. But I am confident that one day we can at least talk about them, even if we don’t agree, but at least us talking and discussing them, means we are not ignoring them, and pretending they don’t exist.

So, Yes! there are a lot of issues I would like to discuss. In Sudan, we have a lot of things that we need to talk about, and we have a long way to go, so that’s why art is always one of the best mediums to discuss all of these difficult topics. It makes it easier for people to discuss it – and if it’s shocking, it starts the conversation ( and lots of hate mail lol). It is not always going to be a pleasant one, but at least it is going to start – especially in a society like Sudan, which has always been all about a certain kind of religion; certain kinds of societal pressures; a certain set of values. So, hopefully, people will start to open up, and start to question things, like they have been more over the previous years. Hopefully, they will come up with new conclusions from the ones they have reached now.

I am always going to feel strongly about black matters; I’m always going to feel strongly about feminism; I’m always going to feel strongly about any kind of inequality, whether it is to do with racism, homophobia, religion, mental health…any of those things.

This is what art – or, at least the kind of art that I like and relate to – does, and it is what I aspire to do. I’m not saying that the art I create does all of that, but this is what I aim to be and do. I could do it right or wrong, but at least this is what I am trying to do.

Alaa: As artists, it’s always important to keep your eyes open and your ears open to what is happening around you in the world. it doesn’t have to affect you personally to care about it. It was really important to me to always try to keep up to date with what’s happening around me. Maybe with the uprising, it was also very interesting to see other uprisings happening in other parts of the world – like Venezuela, Algeria, Zimbabwe or other countries. It was really inspiring to see – and it was also a reminder that all of us were looking for the same things.

We are all looking for life with dignity and peace and freedom

and it’s nice to see how things turn out differently from one country to another, and sometimes also to compare things in other countries to what is happening now in Sudan. Maybe most of my work is directed towards what is happening to me personally, because it is just so close to home and close to my heart, but as an artist, I think it’s really important to use my work to also advocate for other problems and to support other movements that are happening around the world – because, as I said,

at the end of the day, we are fighting for the same things.