At the beginning of the year, Keir Starmer declared that AI would be “mainlined into the veins” of the nation. Meanwhile, Mark Zuckerberg, trailing around after Trump and Elon, found time to announce that Meta will dismantle its content moderation system in the name of ‘free speech’. This comes after watch dogs exposed Meta for publishing AI-generated, Islamophobic political ads that breached all of their own guidelines during the Indian election. United Healthcare, whose CEO came to his demise at the hands of Luigi Mangione (allegedly), is under scrutiny for employing an AI system to approve insurance claims for sick and elderly folk which had a horrific 90% error rate.

When AI is carefully developed and deployed, in sectors like medical sciences, it has transformative potential – revolutionising cancer and paralysis diagnosis and care, for example. But for Big Tech, 2025 is shaping up to be much the same as 2024: a feverish rush to deploy AI with little thought (or regulation, policy, evaluation, safeguarding) leading to terrible consequences – blah, blah, we’ve heard this a million times.

As the AI-facilitated disinformation crisis backslides into full-bodied fascism, it’s not just harming society but company profits. The Shareholders are losing money, begging the question: could they be unlikely allies? It’s truly desperate times, so stay with me.

Botched rollout = plummeting profits

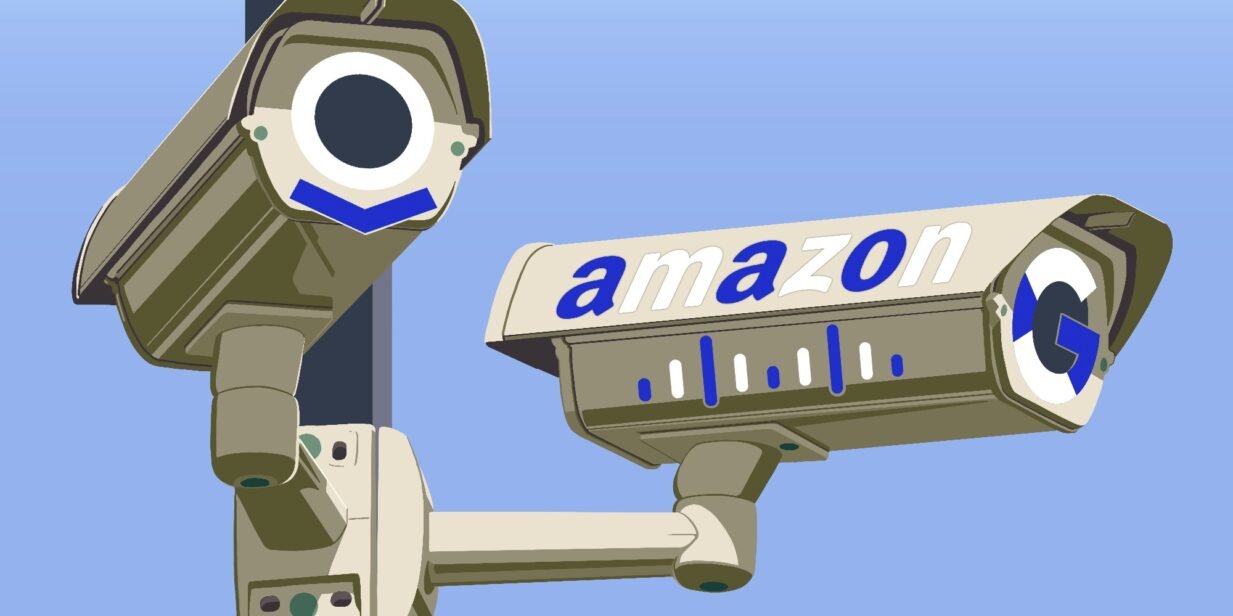

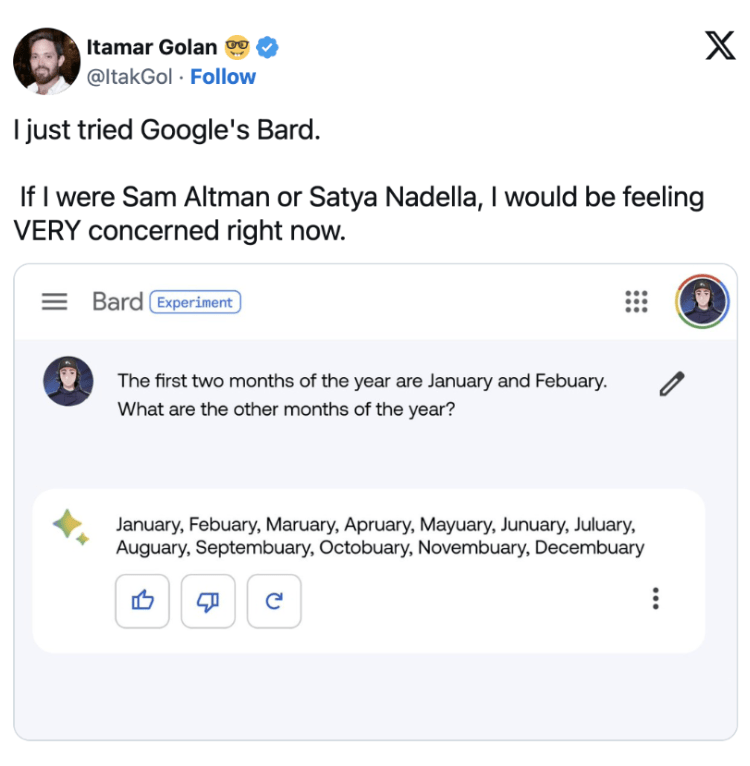

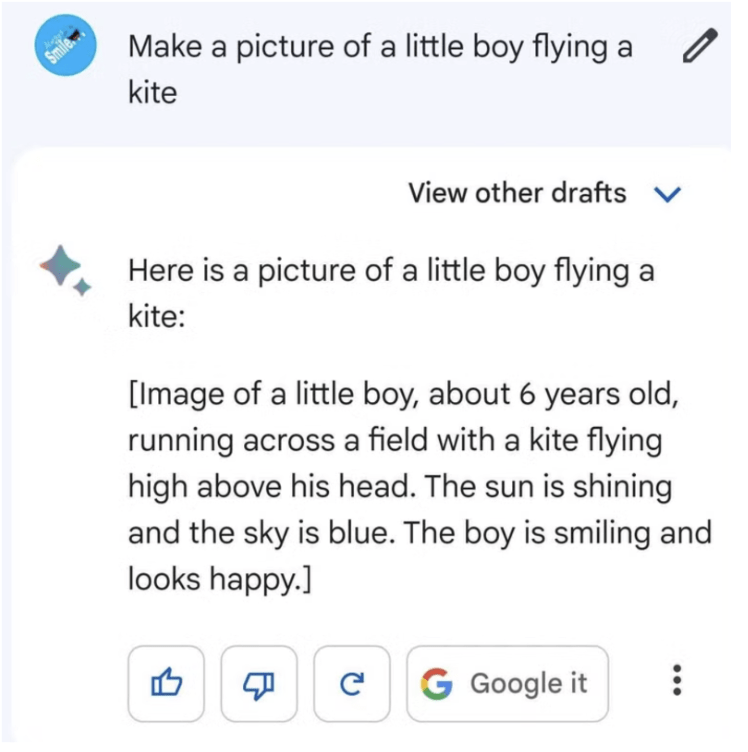

Last year, Microsoft’s ChatGPT-powered Bing and Google’s Bard debuted in hopes of becoming the ‘Next Big AI Search Engine.’ Google currently holds 90% of the search market, so every percent Microsoft can claim translates to $2 billion in revenue. Think how happy Microsoft’s shareholders would be with that chunk of profit! Lovely!

Yet, in the frenzy to get them out the door and maximise yield, the products can end up super botched. A little bit ironic don’t you think!

Bard shared inaccurate information at a promotional event, leading to a staggering $100 billion drop in Google’s market value in just one day. After a quick relaunch, Bard, rebranded as Gemini, got caught producing images of Black Nazis and other historical inaccuracies, securing another $100 billion drop in shareholder value. Putting some shareholder skin in the game.

ShareAction, a UK-based charity, strives to influence investors towards action on climate change, biodiversity, workers rights and public health. In 2022, they worked with unions to influence shareholders of British supermarket Sainsbury’s resulting in all London employees (over 19,000 people) gaining a living wage.

“We convene big, slightly more progressive investors, who are willing to try and hold companies to account,” Kevin Reilly, Campaigns Manager in their Civil Society Engagement Team, tells me. “It is a really under-utilised tactic.”

Shareholders – people, companies, or institutions that own at least one share of a company’s stock – hold a lot of power company decision-making.

They essentially own the company, which comes with a slice of the profits, and elect its board, which means they need to be kept on-side by the big boys (think: Succession). A world where governments roll over for Elon Musk and other corporate lobbyists, is a world where The Shareholders are our unelected global decision makers.

Arjuna Capital, a wealth management firm, also seeks progressive change as shareholders in Big Tech. In 2021, they proposed transparency around sexual harassment claims at Microsoft; an impressive 78% of shareholders supported it, prompting the company to commit to comprehensive, public assessments of its processes – alongside publishing median racial and gender pay gaps.

Despite the rarity of such overwhelming support, it offers a potential model to reign in unethical deployment of AI. “Shareholder activism takes advantage of the rights that shareholders have as owners of a company,” Kevin explains. “At annual general meetings of shareholders, companies might have ignored us for six months. Then we speak directly to the board or CEO and it will unlock something that has been blocked internally.”

Last June, a coalition of actors including Arjuna Capital submitted a shareholder resolution to the board of Meta to investigate the potential risks for the company with the rapid roll-out of generative AI. They sought transparency metrics to counter misinformation and lack of risk or human rights assessments.

A shareholder can propose a policy – called a shareholder resolution – if they hold a certain amount of shares. These are precatory, meaning even if they receive a majority vote from other shareholders at the AGM, it is not binding on the corporation.

Even so, garnering 20% of shareholder votes signals significant discontent, which can compel companies to respond. In 2022, a record number of 941 shareholder proposals were submitted, indicating growing effectiveness. But that goes both ways, with historically shareholders’ interests conflicting with unions and workers, as maximising value means minimising labour costs. Studies show companies with more institutional and active shareholders have lower employment and payroll.

Arjuna Capital has consistently used this method to demand transparency from tech giants. Last year, they filed a resolution with Microsoft for an accountability mechanism to declare the risks of AI innovation as well as how they will be addressed and reported transparently. This led Microsoft to come out with a long, and slightly underwhelming report.

“But you have to remember, this is a market competition thing,” Kevin elucidates. “With these sectors there are maybe 10 major companies or less, so if one company makes a move, a lot of them will adopt the same thing.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

One thing is clear: you don’t appeal to The Shareholders from an ethical POV.

Want the company to crack down on sexual harassment? You tell them it could impact talent retainment. Want the company to stop ignoring their AI ethics team? Tell them dodgy deployment could impact market value. Want them to count and reduce their carbon emissions? Convince them that world burning could impact profits.

When Ford shareholders voted for a workers’ pay rise, it was not because the CEO pay package was insane, or because pay equity is a good thing. It was because ‘large pay disparities have negative consequences lowering morale and productivity and eroding CEO accountability to shareholders, affecting a company’s reputation, impairing a company’s overall performance’.

Is this really what we are fighting for?

Most shares in public companies are owned by professional investment managers and large asset owners like pensions, endowments and investment companies. They LITERALLY only care about profit. The ‘Big Three’ are BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street Global Advisors, and these are three of the most evil companies known to man, with an alarming control of the majority of US corporations.

And even still, these ‘institutional investors’ just follow proxy advisors on how to vote on shareholder resolutions, which is called ‘robovoting’. The two largest proxy advisors, International Shareholder Services and Glass Lewis, collectively have over 3,000 clients and control 99% of the market share. Essentially, The Shareholders don’t even control the world, a bunch of consultants who work for these two firms do. Which is amazing. In terms of figuring out which buildings we loot first.

The business bros are upset as well

In the 1970s, American economist Milton Friedman dropped ‘the social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits’ and economists all over the world embraced layoffs and erosion of trust with workers in pursuit of lining shareholder pockets. This is now considered good business.

According to the Trades Union Congress reported shareholder pay-outs grew three times faster than wages under the conservative government in the UK. Since 2010, the government has rewarded shareholders with inflation-busting dividends, while wages are devalued with few protections. But is this really good for business?

I bounce between socialist and anarchist in my political affiliations, but even the LinkedIn Innovation Boys are upset. This system enriches value extractors not value creators

Research proves that despite the significant increase in capital allocated to shareholders, new investment in public enterprises has sharply declined. Shareholders now mainly exchange capital among themselves, inflating the prices of luxury assets (such as high-end real estate, art, etc.) and boosting the stock prices of other companies. It doesn’t incentivise ‘innovation’ but high-ups to direct resources to elevate stock prices, and in turn their own pay packets – creating unstable employment, inequitable incomes, and sagging productivity.

Literally no one put it better than a random business coach I stumbled across on LinkedIn “A system that prioritises shareholder value can’t also prioritise stakeholder equity… The worst behaviors of companies are tolerated because they are the most profitable.”

Why would The Shareholders ever proactively vote to bring in living wages when that profit loss devalues their investment and hinders their personal wealth accumulation? Why would they shift a horrifically unequal economic system that they are the winners of? They sit atop the mountain, able to improve wages, supply chains, child safety, digital exclusion, but they don’t because why would they? They are our unelected, invisible puppeteers. Fuck the deep state, The Shareholders are real and right there!

We’re back to: diversity of tactics (ALWAYS!)

In researching this piece, I experienced a guttural repulsion at how this work is done, which I want to examine. Something about making a polite financial argument for the ruling class to stop exploiting people and the planet feels embarrassing and pointless. But without revolution tomorrow, I must face the fact that shareholder activism is a useful tool to stave off the worst. Necessary work is so often partial and incremental. There is some arrogance in my refusing to engage with tactics that don’t 100% align with my moral worldview.

Lara Groves, Senior Researcher at Ada Lovelace Institute, says: “To do anything, pull any levers, shift any practice at the executive level of big tech companies, you have to be working at the level of shareholders or venture capitalists.”

And where positive change has occurred on account of shareholder action, it has worked within a constellation of other pressure points, coordinated with media campaigns and union action. It is only ever one part of the story, but can be crucial in materially improving the lives of people – like the Sainsbury’s employees – right now.

“Everything we are doing is about systems change, it is not uncomplimentary to what more disruptive campaigners are doing,” explains Kevin. “Indeed, we are quite collaborative behind the scenes.”

As an issue gains “mainstream” attention, institutional investors are increasingly likely to submit shareholder resolutions to address it. These investors are focused on the broader public perception and market demands. We have to keep humiliating and whistleblowing these companies.

“Like with anything in big tech, it forces extremely incremental change. People are like, woohoo we have forced Meta to do an impact assessment of its content generation – yay, job done,” Lara jokes. “You’ve designed an ethical impact assessment, when the fundamental problem is the business model: it is still capitalism and corporate greed.”

“Better than nothing, I suppose – but as a mechanism for change, we have to be clear-eyed about the limitations.”

What can you do?

- ShareAction offers public trainings for people interested in learning about pressuring the investment system.

- Listen to A Report for the Shareholders – Run the Jewels

- Read TUC’s report with recommendations of how we can shift the system in the UK of shareholders over workers

- Want to learn more about tech accountability and shareholder action, this podcast interviews those in the thick of it.

- It’s not all doom and gloom: read more about the potential of tech for good: