Scrolling on Instagram one day led me to a post from a group called Black Rootz. Their bio read: “The UK’s first Black-led food growing enterprise” – and that fascinated me.

I’d heard of land justice, but didn’t know what this materially looked like in the UK. It was also the first time I’d seen the concept presented through a Black perspective.

Black Rootz is the first Black-led food growers social enterprise in the UK, founded by the Ubele Initiative – an African diaspora-led collective advocating for social and economic change, based in the Wolves Lane Centre in Haringey. It came into being after individual Black growers were kicked out of the Wolves Lane site, prompting multiple groups across London to come together and form a collective which could secure a permanent space for Black growers in the site.

Black Rootz fights for food justice and sovereignty. According to the Trussell Trust, 24% of people from a minority ethnic group experience food insecurity, whilst the figure for their white counterparts is just 13%. According to a report by the same organisation, the former percentage increases to 28% for Black, African, Caribbean and Black British families, the highest out of any group. This links to the fact that two-fifths of Black households live in poverty.

With decades of lived experience of being let down by the government and state, communities know that change has to come from within. This is why groups like Black Rootz have decided to take matters into their own hands. I contacted them on Instagram after I saw their page, and they invited me to their induction that runs every six weeks. There, I was provided an insight to their growing area, the importance of growing organic food, the education and the growing safe space for Black people.

Since then, I’ve signed up as a volunteer and have been aiding growers at the site; mainly with repotting, setting out the beds and planting seeds for smaller plants. I have also learned a few basics such as mixing soil, and what creates the best growing conditions for particular plants. Recently, I learned that compost and coco is the best combination for growing okra.

I’ve picked up tangible experience, and helped upskill others, too. Being in the gardens makes you realise how acquiring and sharing basic techniques are really the first step in tackling food poverty.

Getting into horticulture

Paulette Henry is the co-founder of Black Rootz. She teaches volunteers how to grow a range of food such as potatoes, olives, spices, tea leaves, tobacco – and even paracetamol plants. I met her during this induction day, and a few days later, I got a chance to interview her.

“Growing is in my DNA!” Paulette tells me. Her grandfather was a farmer in Jamaica and provided food that went to market; when her parents came to the UK, her father grew food. Growing up, Paulette and her family – including her five siblings – grew food in the garden and in an allotment space that her father had access to.

She got into growing professionally during her previous job at Haringey Council, where she came across an organisation that trained young people how to grow food in council allotments. While supporting that organisation, she also started her own garden project which brought the community together to use wasteland behind shops in Tottenham High Road, and also worked to help elders in their allotments. This ethos of intergenerational, collective learning is something that is weaved into her practice.

With both her personal and professional attachment to growing, Paulette completed her Level 1 and 2 courses in the subject, as well as Master Gardener training. She came across Black Rootz in 2019 and has been with them ever since.

Black Rootz’s goals

One of Black Rootz’s aims is to get as many people growing organic food as possible. If you go along to their scheme, you then have access to some of the seedings grown at Wolves Lane Centre. “Food is a fundamental right,” Paulette explains, “and working with individuals and communities to grow food fundamentally gives people more access to food itself.” In this way, the organisation is tackling food poverty at its core, by empowering and upskilling people who might not otherwise have the means of growing their own food.

This spirit is embodied in Black Rootz’s ‘Community Growing Programme,’ where members deliver workshops to groups looking to develop their growing skills. Paulette explains that it’s ‘come as you are’ in its nature. “People from different stages will come in and learn how to grow – and they might use this new knowledge and grow in their own gardens, if they have them. We also signpost people to our allotments so that they can share.”

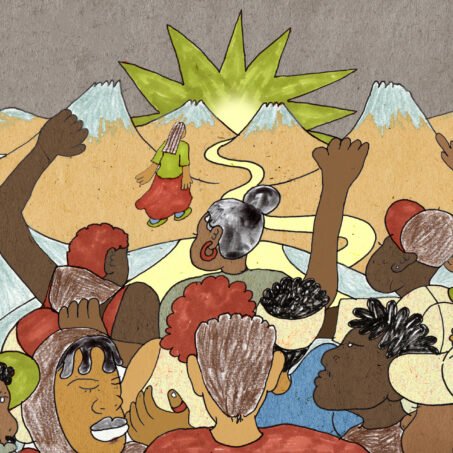

This speaks deeply to our roots in our struggle for food sovereignty. For Black communities in the UK, access to land and food has always been political. Learning how to grow is more than just a skill; it’s a reclaiming. It’s power. Food poverty isn’t random – it’s tied to the systems that have historically excluded us from land. Therefore, coming to a space like Black Rootz means pushing back and building food justice in our communities in the land we’re often denied.

A grower’s experience

Leon Quinlan is a part-time grower for Black Rootz. He was teaching me some basics of horticulture so I spoke to him about his experience with the project. He found out about the project through his old manager and, like me, was interested in how it was a Black-led safe space.

“For the rest of my life, I want to be as happy as I can as an adult and chase happiness rather than just money,” he tells me. “After a degree, two careers and an illness, I decided that growing food was what I wanted to do with the time left.”

Leon only got into growing in his late 20s, although he was always interested in nature. He kept reptiles from the age of 12, and explains that his aunt and father would grow food in the front garden for as long as he could remember. “It starts at home,” he says. “We grew through community gatherings and survived because of it.” He knows more than most the importance of education at home – whether it’s from parents or other family members, this home-grown knowledge is key to equip the next generation to encourage Black and Global Majority folks into agriculture and horticulture, and to combat food poverty.

However, he also acknowledges that there are barriers to families teaching their kids how to grow – and this is particularly in lower-income, racialised communities. Many people don’t have the luxury of time, as they will be working to earn money: something that is particularly stark in a city such as London. Initiatives like Black Rootz are stepping in to provide this education, as they know learning must be a priority in tangibly diversifying the agricultural sector. Without knowledge, it will be difficult to collectively strive for food sovereignty that will help food self-reliance for BPOC and break the cycle of being dependent on a broken government system.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

More than half of British land is owned by the top 1% and the most economically-deprived have less access to public green spaces. Additionally, Black people are four times less likely to have a private garden, balcony or patio at home than white people.

This is due to the flaws in the British system, as well as others which are built on capitalism and colonial legacies. As poverty and destitution continues to increase in the UK, racialised groups continue to be most impacted as a result of structural and systemic racial inequalities.

An initiative like Black Rootz helps combat this lack of access, because they can provide allotment space to those who need it the most. They empower communities by fostering a social connection, creating their space as also a learning hub where people can gain knowledge about growing food, and sustainability. The green space access in an urban area means that people are offered a space to relax, engage and participate in collective stewardship – recognising our reciprocal role in our relationship to nature.

Although Wolves Lane Centre is their main space, Black Rootz has also expanded to Pasteur Gardens, located in the London Borough of Enfield, which is double the size. Paulette explains that this will allow people to have access to land, even if they don’t have an allotment space.

Agriculture: an extremely white sector

According to a report in 2017, agriculture is the least diverse field in the UK, with only 1.4% of farmers being BPOC. Another report revealed that between 2016-2019, around 1% of British agricultural workers came from non-white backgrounds. The evidence is damning.

Sadly unsurprisingly, there have also been multiple instances of racism within the industry. A 2021 report revealed that graduates and students of top agricultural university Harper Adams in Newport reported incidents of blackface, as well as sexism, Islamophobia and homophobia – proving that our struggles are interlinked. It should come as no surprise that the discrimination at this level leads to a lack of understanding of, and access to, culturally relevant foods. When the sector silences diverse voices, it also deliberately blocks out the embodied and taught agricultural and horticultural knowledge of our communities.

This is where initiatives like Black Rootz are essential – and they shouldn’t stop with one collective. Paulette believes that creating a network of BPOC-led collective organisations is our greates solution.“If someone wants to grow something, but those who manage the industry don’t believe a certain food can be grown in this country, then that person doesn’t stand a chance because they won’t be allowed to do so,” she tells me. But if you can teach communities how to grow the food they want to eat, you no longer have to ask permission from an industry that is stuck in a colonial mindset.

Goals for the future

Paulette believes that Black Rootz has been successful in its outcomes of providing a space for Black people to grow, but they recognise that they still have work to do. “To achieve or target commercially, we would need a much bigger space,” Paulette explains. “We want to give people of colour access to clean, affordable food. But since we work with no machinery, we need more people power as the space gets bigger.”

Bigger spaces will ultimately work to address the inequalities and disparities that BPOC face. They can create room for self-governance where decisions about land use, planting, and community events are made by those most invested in the space. Traditional knowledge about food growing and cultural cooking can be preserved and passed down to younger generations, and intergenerational learning can be a model which can be patterned in growing communities and at home.

Black Rootz has grown into a successful project that fights food poverty in their community. It has showcased that it has the knowledge and tools to progress to a hopeful future for greater food sovereignty, in a context where funding and education is scarce. Inspired by Black Rootz, we must acknowledge that food justice – and with it, access to green spaces and land – is a major component of our struggle to total liberation.

What can you do?

The long-term goal would be to eliminate food poverty in Black communities (and also other communities of colour) so that Black people can live a longer and healthier life. This cannot happen without the power of the people.

Read:

- What is Food Sovereignty?

- What are Food Systems?

- Rootz into Food Growing, a 2022 report on a collaboration project between Black Rootz, Ubele, OrganicLea and Land In Our Names, all organisations that work toward food and land sovereignty.

- There are also multiple linked reports on the ‘Resources’ page of Land In Our Names where you can find more information on food and land justice.

- Against western veganism, and other shado articles on food

Volunteer, support and buy food from Black-led Community Gardens

- Follow the instagram pages of Black Rootz and the Ubele Initiative, for more updates. There’s also Blak Outside who I would recommend.