Naghmeh Teymourian-Yates was going to be a lawyer until a pamphlet was thrust into her letterbox telling her that she was going to die. In January 1979 she arrived in the UK as a nineteen-year-old waiting for the streets of Tehran to stop burning. By 1980, Naghmeh’s wait in London had become a permanent exile. Studying to be a nurse as a twenty-year-old refugee was a practical choice. It offered a visa, an education, a career and a stipend. For the last forty years, Naghmeh has worked in the NHS. Nursing was once a desperate choice but she now refers to it as her vocation. She discovered that she was “good with people and people liked me. I loved caring for people and giving back to society”.

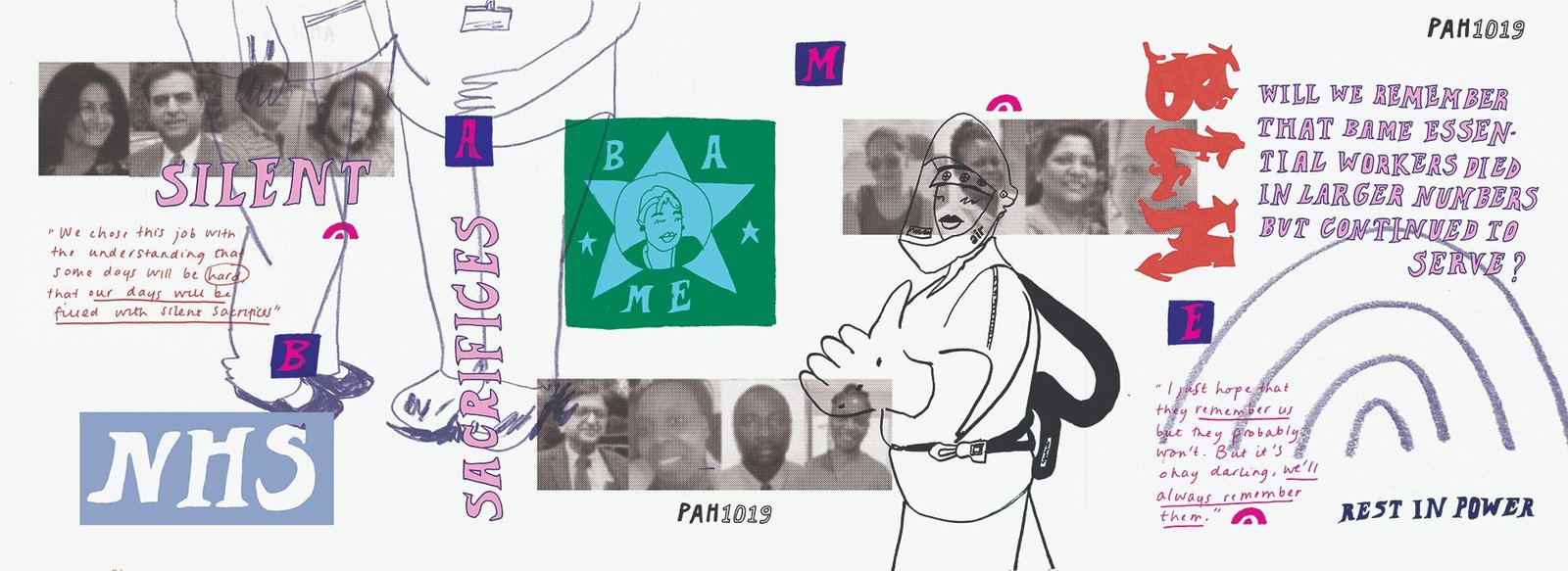

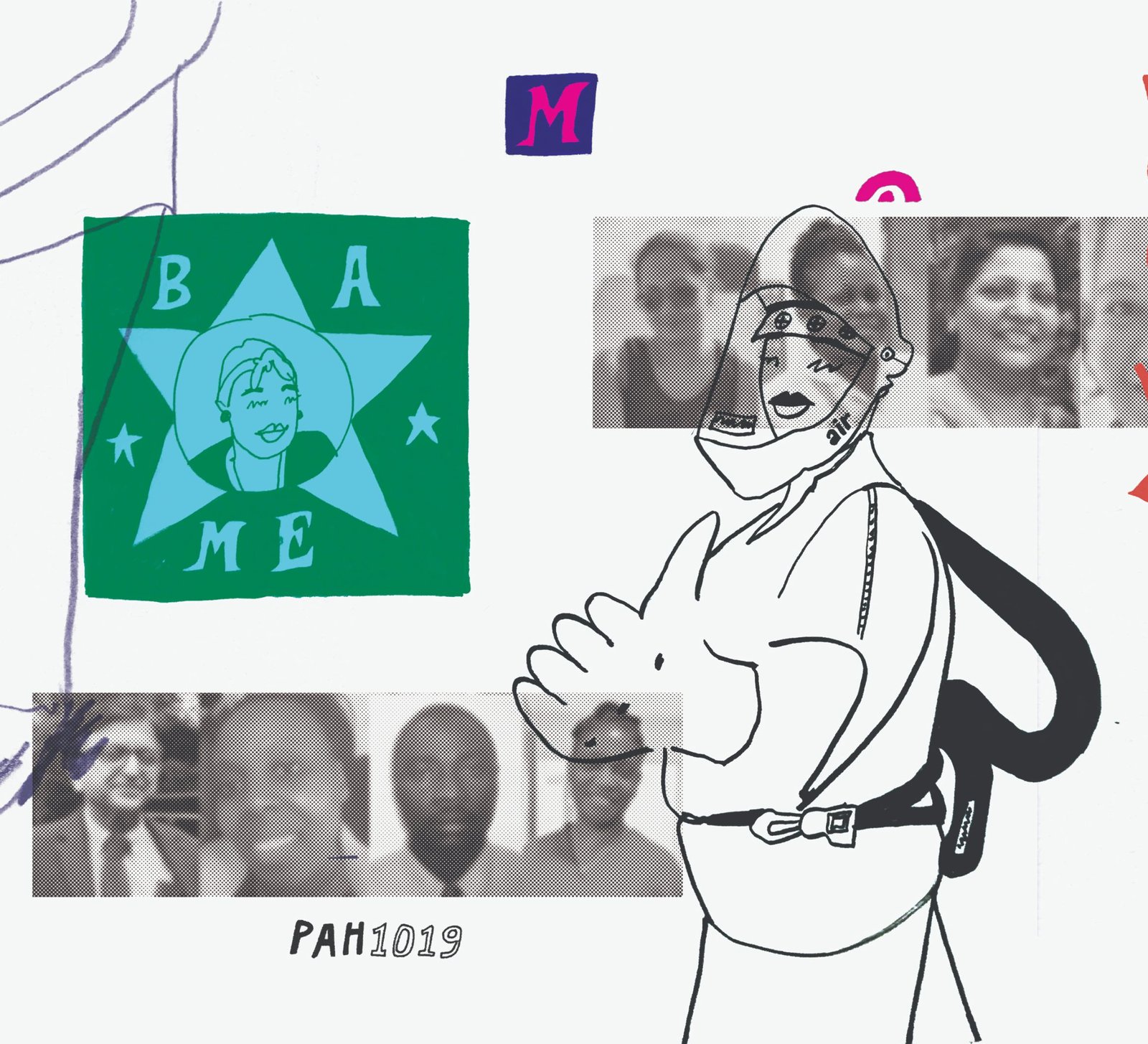

She continues to work in the NHS at a time when BAME NHS workers are the most under threat in the UK. The NHS consists of 21% of people from a BAME background and NHS England has acknowledged that “there is evidence of disproportionate mortality and morbidity against BAME people, including our NHS staff”. Meanwhile, NHS Health Boards and Trusts continue to allow conditions that place the health and safety of BAME workers in jeopardy. “[A] recent BMA survey showed that 64 percent of BAME doctors have felt [pressure] to work with inadequate PPE” in comparison to “33 percent of doctors who identified as white”. In a COVID-19 pandemic setting to be a BAME essential worker is an underlying health risk.

But when there was not enough PPE across the NHS, Naghmeh sourced her own from the local community. Naghmeh’s patients needed her and she wanted to care for them. Like all other BAME essential workers across the UK, she continues to go to work.

COVID-19: A historical moment

In early April during a work break, Naghmeh posted on her Instagram, “We choose this job with the understanding that some days will be hard, that our days will be filled with silent sacrifices.” The day before, her colleague had died from complications from COVID-19. BAME essential workers are continually forced to make the life-threatening decision to expose themselves to COVID-19 in order to take care of us.

This culture of silent sacrifices contributes to the erasure of the magnitude of the risk in which BAME essential workers have continually placed themselves during the pandemic.

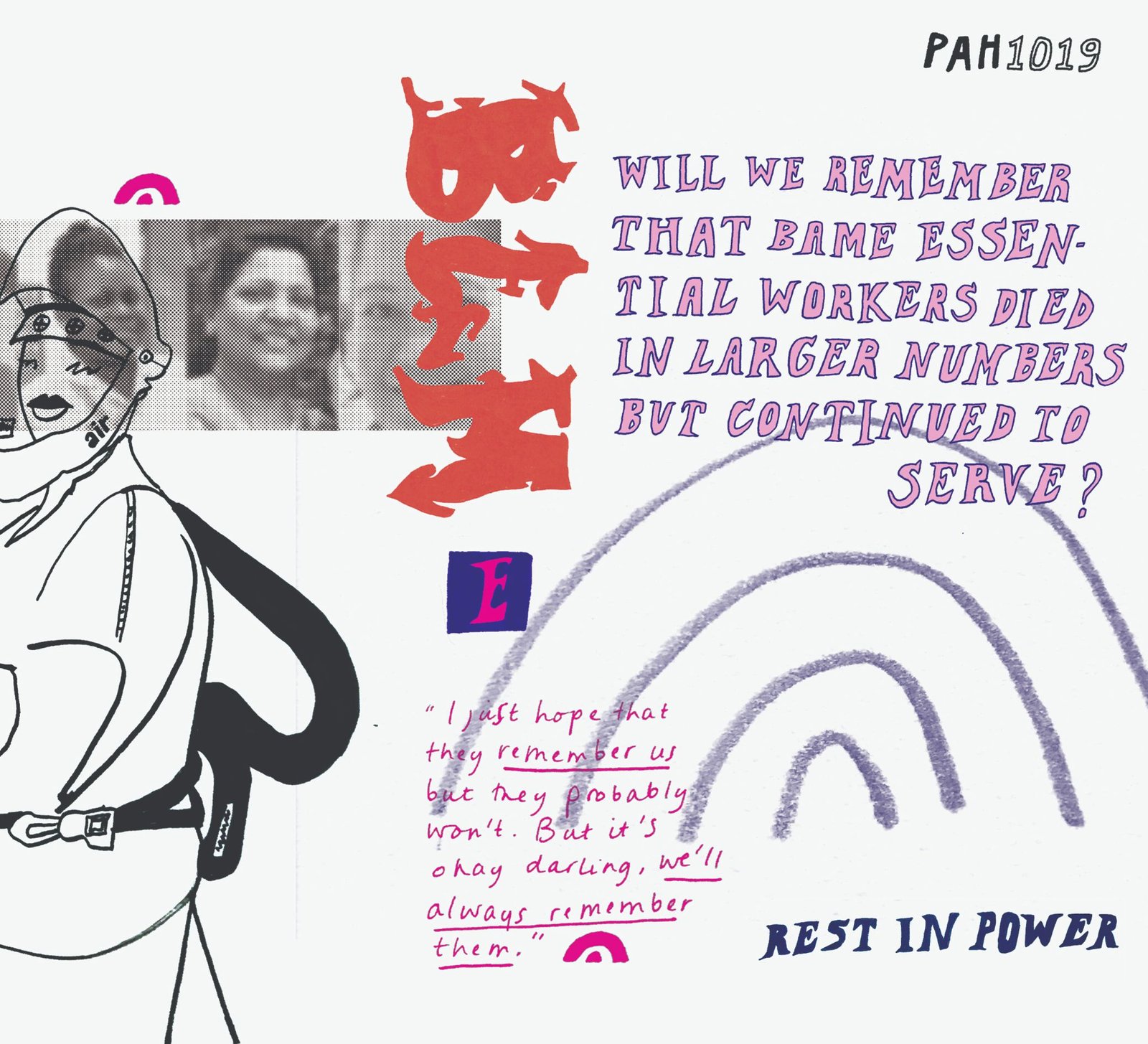

COVID-19 is a contemporary issue that is already being defined as a historical moment. The perception of COVID-19’s impact on the social and political order of the UK is still undefined. Social media is already littered with memes about how we will talk to future generations about COVID-19. But will we remember that BAME essential workers died in larger numbers than any other group but continued to serve their community?

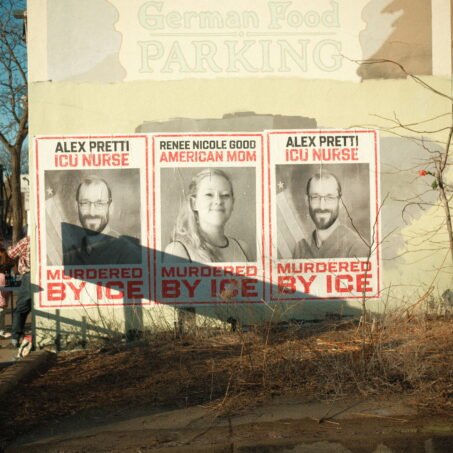

Consistently, historical events have erased the contributions of BAME individuals when their contributions have de-centred the white experiences of those events. Whilst the intersecting events of the Black Lives Matter movement has given us a heightened awareness of how to discuss issues of race, BLM hashtags receded from the social media landscape within weeks of their emergence.

The construction of the story of COVID-19 has begun to be written and the beginnings of how we will perceive BAME essential workers is already being established.

Why are BAME people dying at a higher rate from COVID-19?

Pandemics are accompanied by constructed narratives on why some of us deserve to be sick. Susan Sontag said: “Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick”. Sontag explains that as a society we collectively concoct stories of who deserves to inhabit the kingdom of the well. We make the transmission of a virus an individual choice, a calculated risk that leads to a deserved punishment of sickness.

The pathology of COVID-19 remains uncertain but discussions on BAME mortality rates are already being attributed to the individual choices of BAME people. Early speculation claims that BAME people are more susceptible because of underlying “health issues, living conditions and occupation”. As Operation Black Vote (OBV) stated in an open letter on the 27 May 2020, “They…will say: ‘It’s our genes, our culture, our preferred lifestyle’ – and if we dare speak out about being overly exposed to this deadly virus, caused in part by frontline occupations, health inequalities, social and economic disadvantage, they say we’re pursuing a ‘Victimhood’ agenda’…”.

However, the main demand from the proponents of this “victimhood agenda” is that research and speculation on BAME vulnerability to COVID-19 be met with pragmatism and holistic representations of the BAME experience. An expectation that was not met in a recent report by Public Health England (PHE) that identified statistics on the higher mortality rate of BAME people but did not examine the reasons for the higher mortality rate. The findings made by the PHE were said to include further information about the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on people of BAME backgrounds but was not shared “over fears it could stoke racial tensions”. The British Medical Association referred to it as a “missed opportunity” to provide practical steps to protect BAME NHS workers.

The erasure of BAME contributions to COVID-19

Boris Johnson, after his recovery from COVID-19, specifically praised the efforts of his immigrant nurses. But the Prime Minister has yet to successfully abolish the NHS surcharge for migrant health workers despite consistent pressure from advocacy groups that work on behalf of NHS staff . As Yasmin Alibhai-Brown prophesises: “The contributions of migrants always fall into oblivion. These corona heroes will go the same way”.

In the early 80s and 90s, Sarah Schulman wrote that queer communities bore witness to the deaths of countless friends from AIDS. “[O]ur world was destroyed because of the neglect of real people”. But their stories were re-written by those who lived and who provided “perceptions of the privileged and call[ed] that reality”. BAME people will survive COVID-19 but it will be dependent on mobilisation of BAME people and support from the community to continue to bear witness to the actual realities of those experiences.

BAME NHS workers are currently having to create their own protections and research on their vulnerability to COVID-19. The BMA has repeatedly advised that BAME NHS workers be their own advocates in their workplaces. Perhaps a lack of leadership in protecting BAME NHS workers stems from the fact the NHS executives do not reflect their workforce. Whilst a little under half of the NHS workforce comes from BAME backgrounds only 7 out of 279 of the Chief Executives of the NHS are persons from a BAME background.

Leadership of the BAME experience has had to come from the social media accounts of BAME NHS workers. Instagram accounts with varied followings like @amileya @circa1948.co @gynaegeek @decolonisingcontraception @blackbeetlehealth @naghmehty provide evidence of the lives of BAME NHS workers and how BAME individuals can better navigate the NHS. Like with the AIDS crisis, BAME persons and NHS workers are required to advocate for their own health and safety conditions whilst providing health advice for their community.

Data collection and the BAME experience of COVID-19

In early May, the NHS published a blog about data collection on the BAME experience of COVID-19 for NHS workers. Key areas of focus included the (1) Protection of Staff; (2) Engagement with staff; (3) Representation in decision making. The NHS blog further stated that “data is important, but this is not just an equality, diversity and inclusion issue – it is an urgent medical emergency and we need to act now”. The high death rate continues to be an “urgent medical emergency” but the eventual questionnaire presented to BAME NHS workers did not amount to questions about systems and resources –it was about individual circumstances.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Naghmeh diplomatically demurs in her characterisation of the eventual questionnaire that was presented to her “I ticked the box that asked whether I was from a BAME population, my living situation and I reported underlying health conditions… hopefully it helps!” As OBV articulated the data and information collected by the NHS will contribute to a confirmation bias that depicts BAME NHS workers as agents of their own sickness.

Michael Marmot writes that “people have difficulty making the decisions that will improve their health if they do not have control of their lives”. BAME NHS workers have a lack of leadership in executive positions and endure the dual burden of providing care and advocating for their own healthcare and support in a pandemic setting. However, the questions presented to BAME NHS workers like Naghmeh did not ask how to improve leadership or how to enliven her experience as a BAME NHS worker in subsequent policies to protect BAME workers in a pandemic setting, it asked for her weight and her postcode.

So when I ask Naghmeh about her experiences of being a BAME NHS worker during COVID-19, I ask her what she wants people to know. “I just hope they remember us but they probably won’t. But, it’s okay, darling, we’ll always remember them”.