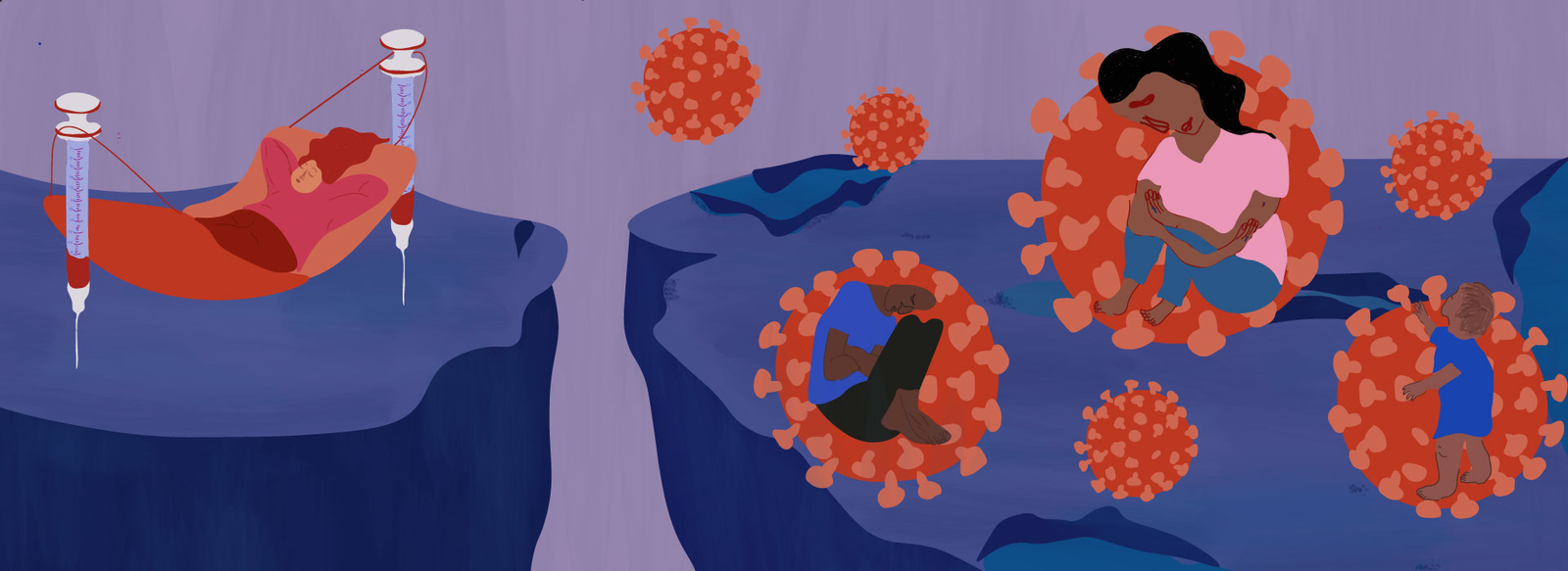

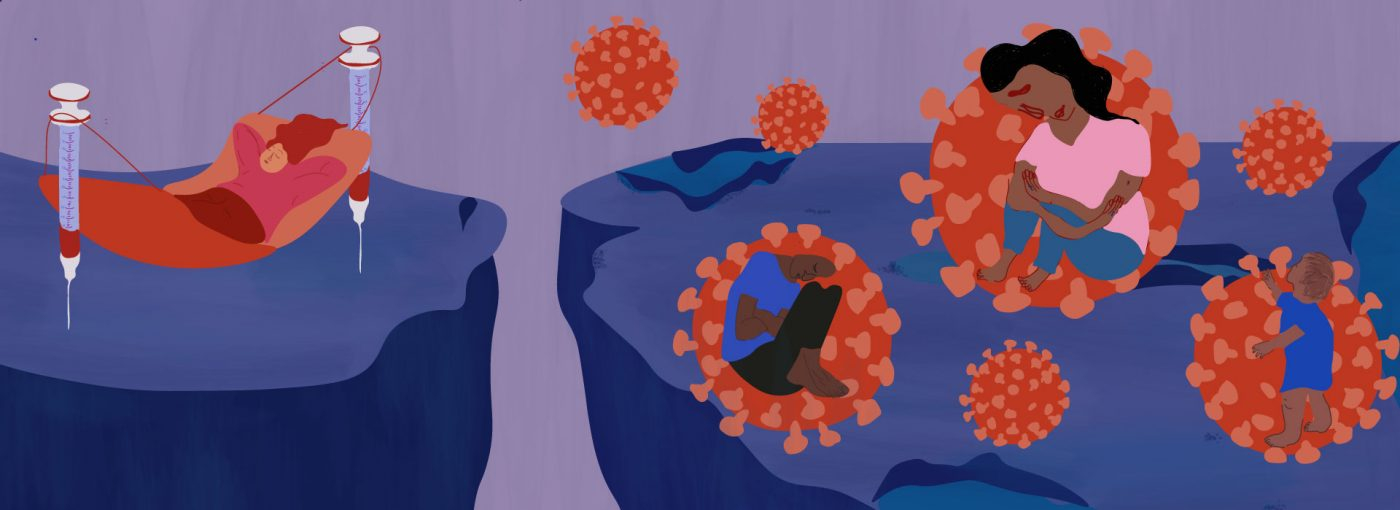

As of July 2021, just 1% of people in low-income countries had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. At least a fifth of the world’s population will not get access to the vaccine until 2022, and many low-income countries will have to wait until 2023 or 2024 for full immunisation. Meanwhile, the Delta variant is surging globally, preying on the unvaccinated. This injustice is not a tragic anomaly, but the predictable result of gross power imbalances between private and public interests, the global north and the global south, and the market-driven world of global trade rules.

There are few concrete incentives built into the medical innovation system other than market-based ones. The global importance of our health and the drive of researchers to contribute to the public good is not reflected in how we govern the system. Instead, the medical innovation system is set up for companies to maximise profit from the volume of sales. The usual mechanism is for the inventors of a health technology to be granted a patent, which can last up to 20 years, enabling them to be the sole manufacturer and distributor of the vaccine or treatment, unless they give legal permission for others to do so through a license.

But this monopoly capitalism has been in conflict with public health interests for many years. HIV/AIDs drugs are now mass-produced and largely affordable only after decades of campaigning by activists across the world forced a change in the system, and yet here we are again, in the next pandemic, wondering how it got this bad.

What gets researched, and who funds it?

Inequity in access to medicines starts in the research and development process. In a system governed by market interest, research is driven to deliver blockbuster medicines, rather than responding to public health needs. Reports consistently find that drug companies spend more money on share buy-backs than research. Health conditions that affect poorer countries with a majority non-white population are frequently ignored, creating a whole category of ‘neglected tropical diseases’. Pre-emptive research into vaccines for viruses of pandemic potential isn’t very profitable, so why bother?

In many cases, public financing steps in to fill the gap and de-risk vital research. Billions of dollars have been invested in the leading vaccine candidates since the pandemic,and multiple successful vaccines, including Oxford and Moderna, benefited from decades of public funding. Despite this, vaccines are privatised with little public oversight, with many of us lulled into the belief that without complete corporate control of health technologies, we’d be starved of true innovation.

Who gets to make vaccines?

In a global crisis, all willing and qualified vaccine manufacturers would be enabled to make COVID-19 vaccines – right? Wrong. The major producers of COVID-19 vaccines currently hold stringent monopolies, enabling high prices and restricting production capacity. New research suggests Pfizer and Moderna are charging up to 24 times the cost of production, and Pfizer is forecast to make $33.5 billion in COVID-19 vaccine sales.

Many believe that potential producers in developing countries are missing out. Both Indonesia and Bangladesh have highlighted the availability of unused vaccine manufacturing capacity. South Africa recently announced the creation of an mRNA manufacturing hub, with President Ramaphosa stating:“We just cannot continue to rely on vaccines that are made outside of Africa because they never come. They never arrive on time. And people continue to die”. An awkward development for the Moderna CEO who stated – “You cannot go hire people who know how to make mRNA. Those people don’t exist.” These arguments echo what was heard during the HIV/AIDS crisis – that manufacturers in developing countries are ‘not good enough’ to make the drugs – often reflecting colonial ideas of western superiority rather than a practical position.

100 countries in the so-called Global South have co-sponsored a resolution, proposed by India and South Africa, asking the World Trade Organisation to waive the global treaty on Intellectual Property (TRIPS) for the duration of the pandemic for COVID-19 purposes. If adopted, countries would not be sued if they choose to temporarily not apply, implement and/or enforce patents, protection of data, industrial design and copyrights related to COVID-19 health technologies. However, a small group of high-income countries continue to oppose, block or stall the proposal – an easy position to take when you have plenty of vaccines for yourself and the companies are based in your countries.

Whilst leading pharmaceutical companies have claimed that patents are not a barrier to global equitable access, a recent network analysis published in Nature reveals a web of patents, licenses and development agreements impacting COVID-19 vaccines. Meanwhile Bolivia, who have only vaccinated 5% of their population, are asking Canada to grant a Canadian company a compulsory license to produce COVID-19 vaccines so that they can import them, a situation the TRIPS waiver could help solve.

In the case of COVID-19 vaccines, patents, many of which have not been formally granted yet, are far from the only barrier. To manufacture complex vaccines, technology transfer, where know-how is actively shared, is essential. Waiver critics including large pharmaceutical companies and the EU say that voluntary licensing and technology transfer are much better alternatives to the waiver for this reason. Awkwardly, a technology transfer pool for COVID-19 vaccines and more (C-TAP) is already available at the WHO. Pharmaceutical companies can openly share the IP, data and know-how with WHO qualified manufacturers voluntarily. It remains unused. Instead, companies such as Pfizer and AstraZeneca have opted for secretive and limited agreements with other manufacturers, where they retain control over the underlying technology as well as where, to who and at what price vaccines can be sold. True sharing would create rival manufacturers with the ability to develop the technology further, and why would a company voluntarily do that? Especially when the future of mRNA looks so profitable. If our only option is to rely on markets, public health looks to be in trouble.

Who gets to buy the vaccines?

Of course, increasing manufacturing capacity might not improve global vaccine inequality if rich countries buy all the doses. With limited supply, a highly unequal global economy and no regulation on price or procurement it is hardly surprising that in late 2020, Oxfam reported that “rich nations representing just 14 per cent of the world’s population have bought up 53% of all the most promising vaccines so far”. The UK has ordered enough vaccines to vaccinate three times its population. Rich countries are now vaccinating children and debating third shots in the Autumn, despite the WHO calling for a moratorium on booster shots. Meanwhile, Pfizer and Moderna have announced intentions to raise the price of their vaccines, highlighting a clear strategy to sell to rich countries and maximise profits, rather than aiming to end the pandemic at a global level.

Developing countries can supposedly access vaccines and financing through the ACT Accelerator and its vaccine arm, COVAX, which purchases and receives donations of vaccines from pharmaceutical companies and high-income countries. As the product of the Gates Foundation, steadfast supporter of monopoly rights, the initiative has been criticised for failing to tackle the root causes of vaccine inequality and relying on fickle charity. The ACT Accelerator has been held up by Gates and the industry as proof that “the industry is already doing all the right things” and more drastic measures, such as the C-TAP and the waiver, are not needed. But why should billionaires decide how we respond to a pandemic?

However, as rich countries who state support for the mechanism continuously bypass the mechanism through bilateral deals, COVAX has run into significant supply shortages. MSF estimates that ‘Pfizer-BioNTech has allocated only 11% of their deliveries to date to low- and middle-income countries directly or through COVAX, and Moderna has allocated only 0.3%’. As stated by South Africa at the WTO Trips Council in February – “the model of donation and philanthropic expediency cannot solve the fundamental disconnect between the monopolistic model it underwrites and the very real desire of developing and least developed countries to produce for themselves”.

We need a new system

If we allow the status quo to continue for COVID-19 vaccines, we can expect unnecessary death, suffering and injustice. Instead, we must challenge the entire way we think about innovation and public value. What if vaccines were treated as a public good and governed in the public interest? What if companies agreed to openly license their vaccines? What if governments financed mass technology transfer?

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

What if we did all of this, and then asked – why not every medicine? What if we invested most into the diseases which cause the most harm to people, no matter what country they live in or their income? What if we built a system that valued all life equally? For some, the chance of wider system change is a reason to block the TRIPS waiver and C-TAP. But for public health and global justice, a radical rethink is nothing less than essential. Some people are already building an alternative, like the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative, an equitable innovation organisation who have developed nine treatments for six deadly diseases which affect the world’s poorest.

The fight for health justice has been won before and can be won again. The United States has backed the TRIPS waiver in response to huge public pressure. Oxford University imposed price conditions on AstraZeneca. The pandemic has seen notable innovative research into low-cost ventilators and test kits designed for low-income countries. Vietnam and Cuba have developed their own vaccines. Thousands of people in the UK are campaigning to end vaccine apartheid with Global Justice Now, UAEM, STOPAIDS, Just Treatment and more.

The pandemic has shown us the best and the worst of how we might meet our global need for medical treatment. Global vaccine apartheid is an active choice. It’s now time to go back to the drawing board and design a system that puts public health and global justice at the core.