Guerrero means warrior in English. A fitting name for the state in Mexico that has historically been a refuge for rebels and revolutionaries. A state where violence, narcos, transnational companies, poverty, neglect and counterinsurgency programs have made fighting for life and autonomy the only option for many communities.

In the jagged mountain range where the second biggest production of heroin and poppy seeds in the world lies, where mining concessions have plagued the territory, where death and disappearance is a constant reality and where corruption and impunity are the norm, an Indigenous and afro-descendent organisation was born called the National Indigenous Council of Guerrero – Emiliano Zapata (CIPOG-EZ).

For five years, the CIPOG-EZ had advised against entering into their territories because it was too dangerous. But on 2nd April this changed.

They welcomed us, as part of the Caravan for Water and Life, into Alcozacan, Chilapa, the heart of their liberated territories.

Their communities are currently under siege by organised crime groups, Los Ardillos, Los Rojos and Guerreros Unidos, and their struggle is not covered by mainstream media.

The Caravan intended to help amplify their message and to build stronger connections with them and other communities of resistance. But this did not come without risk.

“Close the blinds and don’t look out the windows.” This was the instruction from a CIPOG-EZ member that came through the walkie talkie.

We were passing through a checkpoint manned by Los Ardillos, a narco-paramilitary group known for their extreme violence in the mountainous region of Guerrero. Just the day before, six decapitated heads were found in the municipal centre, suspected to have been planted there by them.

The bus wound down the mountain road following the CIPOG-EZ’s pick up truck. Through the curtain gaps we could see armed men with covered faces lining the side of the road.

It was on this road that two members of the CIPOG-EZ, Pablo Hilario Morales and Samuel Hernandez, were stopped by the municipal police of Atlixtac in January this year and then never seen again. There is an ongoing investigation into their forced disappearance.

Alongside controlling various drug trafficking routes, Los Ardillos also carry out extortions and kidnappings in order to make money. They have participated in some of the most extreme crimes in this region, from massive disappearances to massacres, and have been specifically targeting Indigenous communities, like the Na Savi, Me ́pháá, Nahua, Ñamnkué and Afro-descendent communities that have been defending their lands. These communities also form a part of the CIPOG-EZ.

Using torture, assassinations and disappearances, they have spread fear and broken down the social fabric of communities. Whole communities, like El Paraíso de Tepila, have been forcibly displaced by this violence.

For years, their main business has been the clandestine cultivation of poppy seeds and the production of heroin. But with a slump in heroin prices, the CIPOG-EZ and various local reporters say that Los Ardillos have branched out into working with the mining industry, possibly offering protection in exchange for pay. As well as using intense violence to quell local resistance to the extractive industry.

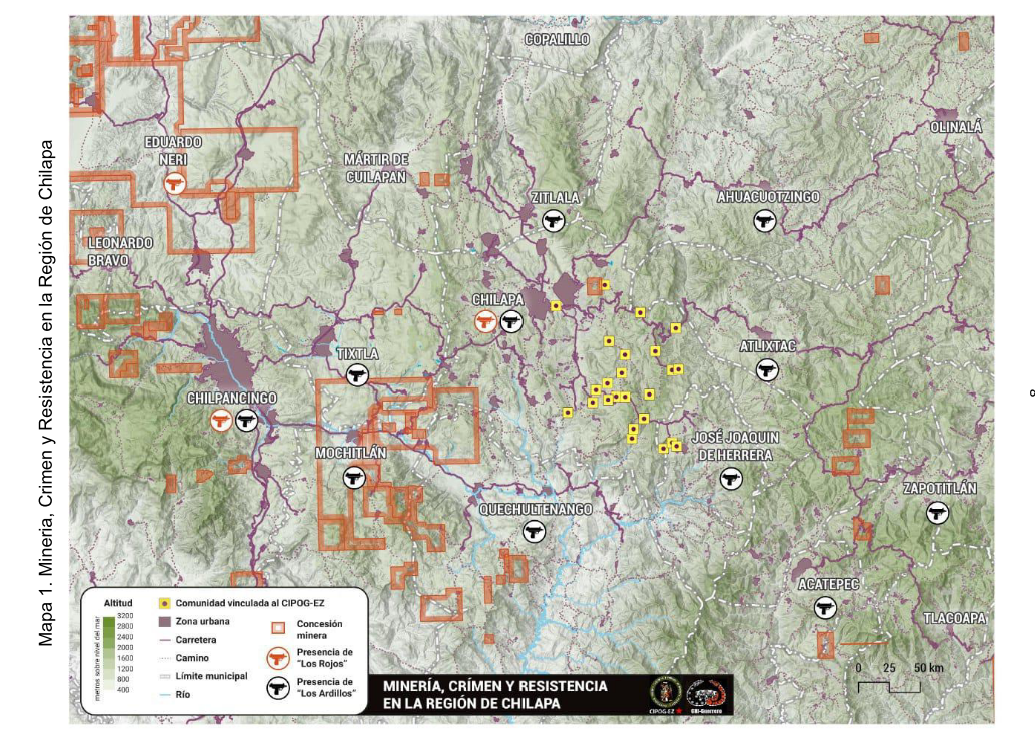

They say it is no coincidence that sites with mining concessions are zones where Los Ardillos and other organised crime groups have their bases, as shown in the map below.

The red squares are mining concessions. The black symbols signify the presence of ‘Los Ardillos’, and the red ones signify the presence of ‘Los Rojos’. The yellow squares represent CIPOG-EZ communities.

After over 18 hours of travelling, we finally arrived at Alcozacan.

Enclosed in a valley of mountains, isolated from the outside world, we were met by hundreds of men and women from the CIPOG-EZ.

The men were armed with hunting rifles, their faces covered with bandanas, and the women were dressed in their traditional Nahua clothing with coloured rebozo shawls covering their heads. They gave such an impression of strength, it was good to know that they were on our side.

As diaspora, we always hear about the death and destruction that plague our countries. The images of migrants aboard trains or the news of narco massacres are constant. But it is rare to see images of our communities resisting in the face of this violence.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Seeing the CIPOG-EZ that day transmitted an energy that was rooted in power and dignity. Suddenly I understood what it must have been like to stand with the Black Panthers or the Zapatistas.

Power is a word that is often understood in the West as the violent use of authority and something to be scared of. In our heritage communities, it is entirely different.

Power is collective. Seeing and feeling a community stand up despite having all the odds stacked against them, and build autonomy, showing que si se puede, that it is possible – is an embodiment of power. It is a feeling to be embraced and replicated.

As the Caravan and the community marched up the mountain, towards the centre of the community, chanting slogans of resistance, it felt like in this valley of mountains, a fire was kindling.

When asked about their decision to arm themselves, a member of the community explained, “It is self-defence. We don’t want violence in our communities, all we want is peace, but we won’t just let them kill us and take our lands.”

The CIPOG-EZ believe that several municipal governments and police forces are colluding with organised crime groups and that for this reason, despite the regular attacks that occur against their communities, the local, state and federal government almost always turn a blind eye.

The community have recorded 40 assassinations, 19 disappearances and, as a result, 66 children made orphans within their community. They say that their only option of survival is to defend themselves.

For this reason, the CIPOG-EZ communities also form a part of an Indigenous community police force, called the Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities – Community Police – Founding Pueblos (CRAC-PC-PF), an organisation that deals with security and justice in their territories. All indigenous communities have the right to self determination and to self govern in line with their traditions and customs – this community police force falls under those rights.

They explain that this form of organising is derived from five centuries of Indigenous resistance and that representatives are chosen through assembly and do the service voluntarily. “Justice has existed in our lands long before the invaders came and imposed their laws,” shared a member of the community police force. He expressed that this is them reclaiming that.

The community police force is a beacon of inspiration for many of the young people and children in the town. But it is not easy work. Once the sun went down, we were invited to see what their night patrols looked like.

Pickup trucks bristling with armed men drove down the mountain’s dirt track road. Everything was silent, only the light from the headlights could be seen in the dark of the night. We stopped at one of the CIPOG-EZ’s checkpoints, where a few men were on guard. Checkpoints are positioned all across the community and are in constant communication with each other.

Laughing about the close shaves that they had had, members of the community police shared stories of times Los Ardillos had come close to killing them. As they spoke, there was a sense of carnalismo, brotherhood, between them. You could tell that in every laugh, there was a deep understanding of what they were up against. They spoke of the importance of their lands; how they would rather risk their lives and die in this struggle than see their people dead or displaced.

One of the community policemen whispered into another’s ear. A message had come through, alerting them to a threat from Los Ardillos. As a warning, they shot bullets into the air, sparks lit up and the noise echoed around the mountain. We were quickly rushed back to the safest place, the community centre.

When we arrived, we were informed that in Colotepec, a nearby community under Los Ardillos’ control, 50 trucks and 20motorbikes loaded with armed men were seen organising themselves, for what the community thought might be an assault.

The CIPOG-EZ claim that every time they hold events or invite media into their territories, Los Ardillos host attacks, shooting at houses with children, women and elders, in order to scare journalists and organisations from visiting their communities and denouncing their reality. The community police quickly mobilised.

One woman, who was visiting the community from a nearby region, began to cry, saying that her husband had been killed by Los Ardillos, and that she needed to be alive to look after her children.

A member of the CIPOG-EZ called over a nine year-old boy from the community to reassure her. “What do you do when there is a shooting?” he asked the boy. The boy answered nonchalantly, “I just lie down and listen to the bullets. When they stop, I get up again and carry on with my day.” He shrugged his shoulders.

The man looked back at the woman and put his hand on her shoulder. “Just know for them to kill you, they first have to kill all of us,” he said. “Do not cry, or you will make me cry. We are strong, remember that.”

It is in this context of violence that this community does not only decide to resist but also sees that building autonomy is their only option.

Jesús Plácido Galindo, one of the community’s Indigenous council members and a member of the National Indigenous Congress, explained that they are currently working on building community radios and community schools to strengthen their autonomy and raise political consciousness. They are also working on putting together a coffee and honey cooperative.

“In our communities, autonomy is our only option. We have to build our own education system, health care system, security and justice system, media and food sovereignty because the government and its institutions have totally failed us,” says Jesús. “The narcos threaten the teachers and doctors to leave our communities so that our children can’t go to school and so that we don’t have access to health care and the government does nothing. We can only rely on ourselves.”

The CIPOG-EZ wants to build schools that teach the community real skills to help them build capacity in their resistance.

Some of the areas of learning will be agro-ecology, production and internal economy, community health and community communication. They organise through the principle: build don’t destroy. Believing that through building a better world, other communities will see that there are alternatives and follow suit.

They emphasise that they are not like political parties that just make empty promises to get elected and then leave communities on their own. They say they lead through their actions, not their words.

Jesús knows that in doing this, there are serious threats. “Many have been killed in this fight for life. They are saying they will give anyone $30,000 pesos (approx. £1200) for my head,” he says. “We are confronting some of the biggest powers in the world, narcos, the government and transnational companies, it is no wonder they want us dead.”

A communique came out from the CIPOG-EZ naming Jesús Plácido Galindo, Isaías Posotempa Silverio, Adán Linares Silverio, Benjamín Sánchez Hernández, and the families of disappeared Pablo Hilario y Samuel Hernández, saying that they are being targeted by Los Ardillos and responsibilising the Mexican government for anything that is to happen to them.

“If there is one thing that our communities have learned in these 500 years, it’s to have dignity. We would rather die on our feet than be killed on our knees.” expressed Jesús.

The next morning we left the community, escorted by the CIPOG-EZ. There was a nervous atmosphere; it’s one thing entering a community, it’s another thing leaving. With the threat of the night before we weren’t sure what would happen. When the bus passed out of the state borders, into Morelos, there was a sigh of relief. But we knew that the CIPOG-EZ was still there and that their people continue to put their lives on the line every single day.

The story of violence and extractivism working hand in hand is one that is replicated across the continent. In Abya Yala (Latin America and the Caribbean) colonialism never ended, it just transformed.

Vast parts of the region are still concessioned to foreign companies that continue the extraction of natural resources, minerals and metals whilst local Indigenous and campesino communities do not reap the benefits, and are often displaced, persecuted or killed in the process.

The essential component in all of this is land. Communities building autonomy and taking back their lands is true decolonisation – and we must see and support these struggles as national liberation efforts.

Solidarity must not just be mobilising when our people are killed or disappeared but rather building long term infrastructure to support their movements. We need Jesús Placido Galindo alive, as well as all other members of the CIPOG-EZ communities. They are our liberation fighters, and an example to communities everywhere of resistance.

This piece is the second piece in a series documenting resistance struggles across the central region of Mexico and a Caravan that united them. Read the first piece in the series HERE

What can you do?

- Find out more about the Caravan HERE

- Follow the group on Facebook Concejo Indigena Y Popular De Guerrero – Emiliano Zapata Cipog-Ez | Facebook

- Follow the Congreso Nacional Indígena on Facebook, or visit their website

- Support the CIPOG-EZ financially. Money goes towards supporting community radios, schools and coffee and honey co-operatives. www.cash.app/£CipogEZ