As a belated birthday gift, a friend took me to the cinema to see Sinners. The latest offering by filmmaker Ryan Coogler, explores the role of Irish immigrants in American history through the metaphor of vampirism. Within the first 15 minutes of the film, I leaned over the seat and said: “I already want to watch this movie again!” By the time the film ended, I had a 35-page essay brimming at my fingertips.

Each scene’s masterful storytelling reflects human complexity in ways that clearly identify the villains, while also depicting the uncomfortable, interconnected relationships between villains and victims. The complex treatment of historical narrative gives viewers a delicious array of Wikipedia rabbit holes to dive into, while also encouraging creativity and imagination in our analyses of what we see on screen.

Jumping timelines and genres, the film cannot be pinned down to belong in any one place, and while it is considered part of the horror genre, for many, the metaphors do little to obscure the realities we still live with. In the vein of imagination, one scene in particular gripped me: a sex scene.

[Potential spoiler zone]

Set in 1930s Mississippi, the lifeworld of Sinners is a dangerous place. Shooting someone in the knee because they annoyed you is a simple disagreement, Jim Crow laws are the moral compass of the society and the Ku Klux Klan is the (un)official law enforcement agency.

Twins, Stack and Smoke, have recently returned to their hometown after fleeing trouble in Chicago. With stolen money, they purchase a sawmill which they want to turn into a juke joint for the local Black community. To set their plan in motion they split up to recruit the help needed to run the establishment. Smoke stops by Annie, his estranged wife, to convince her to run the kitchen. Their estrangement is palpable and their first encounter is strained and antagonistic, partly due to the ghosts of their past, one of which, a child, is buried on the property.

Their duel continues before their mutual longing draws them closer to each other. Having been apart for years, this reunion is difficult. As they both cave to their longing for each other, startled by the visceral pleasure of touch, they start fondling each other, with Annie leading the exploration. In their shuffling, Smoke turns Annie away from him and enters her from behind.

Reflecting lived realities through queer optics

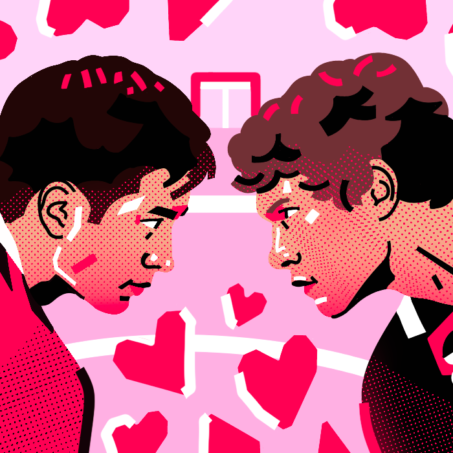

The optics of this sex scene are so recognisably queer. The scene sketches an urgency in the sex we see there, as there is no time for a paced intimacy. It is consuming, it is unhinged, it is desperate. I don’t mean to suggest that sex between queer people only adheres to this bodily configuration, nor that sex between heterosexual people avoids such configuration.

However, if you have been alive long enough, you will know that the sexualisation of queerness is animated by the stereotypical act of “getting fucked in the ass”. This act is not imagined as romantic, loving, or endearing at all. It is imagined as impersonal at best and violent at worst.

The absence of face-to-face contact sketches sex as being done by one party and done to the other party. Its optics are often animalised too – an element of the homophobic imagination that serves to justify the oppression of queer people. Erased from this imagination is, of course, a whole world of sapphic relationships that are invalidated by the patriarchal homoerotic thrust of thought around queer or, more narrowly, gay sex.

In this scene, their bodily configurations lend itself to affirming their fugitive existences. Smoke is on the run from his life in Chicago, but as Black people in Jim Crow Mississippi they are both constantly under siege and need to be ready to run or fight. Any momentary pleasure, even after such longing, cannot risk disarming them under such dangerous conditions.

For me, the film shows a common experience of fugitive existence for Black people who are vulnerable to the violence of white supremacy. Hence, in a white world, Black life is queer. From this perspective, it invites us to explore the thread that connects Black life to queer life in a way that makes Black life queer, and queer life Black. This is also pulled through in the metaphor of the twins who could be seen as Queerness and Blackness, and as illustrated, later if they are forced apart and estranged, they both die.

Telling authentic stories allows everyone to see themselves clearer

I spoke to Dr Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi, sociologist and shado editor, to think through this relationship between Blackness and queerness. Though we agree that Ryan Coogler probably was not trying to surface this relationship intentionally, what we are identifying is an outcome of authentic storytelling that welcomes complexity.

“I feel like there is an inherent relationship between all of these [things] that no matter the story you try and tell, as long as you’re telling it authentically you will inevitably have something really smart on your hands,” Adebayo muses.

This point is instructive to creators and artists who often get hamstrung by the imagined impact their work will make, or fail to make. In an era where relevance relies on bombarding audiences with endless outputs to feed the insatiable culture of consumerism under late-stage capitalism, referencing facts, even in works of fiction, still promises us a chance at something beautiful. This “something beautiful” is a sense of relation that offers our audiences an opportunity to be seen in art.

Adebayo continues: “I don’t necessarily think Ryan Coogler is thinking about all of these things that we’re seeing. I mean, I’m sure he’s smart as hell, and he really has put a lot of details into these things, but I’m sure that there’s so much that he hasn’t thought about but we’re thinking about, because he has presented something that is truly artistic. Right? And so it means that different types of people can see, it can fit into various worldviews because it is a reflection of the world that we live in.”

Although set nearly a century ago, the world sketched in Sinners is familiar – even while creative storytelling and the use of the supernatural might attempt a distancing. For Black people, the world is still a dangerous place that requires hypervigilance, agility and endurance to navigate somewhat successfully. This experience of danger is mirrored in queer lives, and when superimposed on Black experiences, queer and Black experiences reveal themselves to be twins, identical, but not fully symmetrical nor indistinguishable.

A framework for grounding cultural memory

On this idea of mirroring, Adebayo offers some of his recent work which has explored a framework for understanding how we evoke cultural memory through art. With Sinners, Ryan Coogler uses historical memory as scaffolding for a metaphorical treatment of the history of white supremacy in the USA, making very clear points about its impact on Black life. This impact is explored with tenderness and complexity to render a story where even the less obvious themes can be seen by those with the sight for it.

“It’s an idea of how artists are able to evoke cultural memory. And I think he does it so beautifully in this,” Adebayo says. “Because we came up with a framework, which was Acknowledge, Refuse, Localise and Mirror. And when you think about all of these things, it starts off with acknowledgement of the world that they live in: we see it’s a racist world, we see the Klu Klux Klan, we see that it’s a violent world. But at the same time, he does it with a refusal: a refusal in how they have sex, a refusal in how they embody space, a refusal in whose perspective we get to see.”

The framework Adebayo shares offers an excellent tool for grounding us in our approaches to artforms that sometimes threaten to snap its tethers and float away into obscurity. Though I don’t want to suggest that obscurity in art is inherently bad – of course we need pathways into dreaming that cannot be weighed down by current realities. However, equally important is how to treat, artistically, the representations of the shared experiences that so many of us rely on to make sense of the world. This is also a responsibility we undertake when telling stories in a time when self-expression and truth-telling is being brutally repressed.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Adebayo continues, “The next thing is to localise. He localises the story, the thought, the process to a very specific state of Blackness. The music is very specifically Black. The way they dance, the way they move, the way they talk, the way they occupy space, the way they dress, the way the religious process is – everything is so specifically Black and localised in the context in which it speaks.”

Here Adebayo demonstrates the grounding effect of applying specificity to a story that can still be universalised. The universality is, in fact, inspired by the specificity because when we see people in their intimates, we cannot help but recognise the humanity we share with them.

“And the final thing is mirroring: it reflects back something to everybody. So we are all able to get something from it because we’re able to see ourselves in different ways. And a lot of that is precisely because of the way that Coogler has depicted this world,” Adebayo concludes.

We don’t always need queer characters to depict queerness

If analysed for its engagement with queerness, most would find close to nothing, but Adebayo and I agree that it doesn’t need an obviously queer character to make the point. It is because the story about Blackness has been told with that level of care and interest that we are able to see all that lives in relationship with it.

Within this film, we see the dynamics of queerness in relation to Blackness because within each experience, the other is already there. For both of us, this surfacing of queerness in a movie telling intentionally Black stories reflects the point that those who experience queerness can see it in Blackness. This recognition is not forced nor manufactured when we see that the relationship between these two sets of experiences is familial, through a shared sense of otherness.

The symbolism of the Twins, Stack and Smoke, can then be seen as a representation of the interconnection between Black and queer life in a world that others both. While they start off as inseparable and fiercely protective of each other, at a later point in the film, Stack is ‘turned’ and joins the community of vampires led by white people. This signals the demise of their relationship as clear lines are drawn between “us” and “them”.

This narrative, although a clear statement about the appropriation of Black sociality by whiteness, which is depicted as exploitative, extractive, and harmful reflects the optics of the debates that often villainise Black queer people as traitors to Blackness, and tools of whiteness.

On the demands that such atomistic approaches make of Black (and) queer people, Adebayo says: “You can’t be at the door, right? Like. you either need to be inside or you need to be outside. Which is why even the symbolism that Ryan Coogler established is so strong: you’re either in or out, and being at that in-between, you can’t do it.”

Reflecting on his own relationship with the disjuncture between Black and queer spaces, Adebayo notes trying to experience his Blackness in queer spaces has been a somewhat joyless attempt at being “at the door”. Being fully in requires him to privilege the experience of queerness, which involves an amputation of his Blackness.

“The relationship between the queerness and the Blackness is really strong because of how much they’re both so fundamentally constructed in the same way, but we have separated them so much that actually it’s killing them both. It’s killing both spaces that both parties are developing. That’s why the end of Sinners is not a happy ending,” Adebayo reflects.

Separating Blackness from queerness forces unhappy endings

The unhappy ending of Sinners, perhaps unconsciously, makes a bigger point about how, when divided into social silos, Black and queer communities are condemned to dysfunction brought about by a loss of connection between related experiences.

Within this dysfunction is the loss of a shared language with which to understand each other, the loss of shared strategies to protect each other, the loss of histories that corroborate shared experiences, and the loss of sight to recognise each other. When lost, the absence of these resources creates the impression that the two experiences, Blackness characterised as conservative and queerness characterised as deviant, are enemies serving the same master: white supremacy.

The layers of interpretation that could be applied to any scene or theme depicted in Sinners, invite all of us to read our experiences into it, while it demands our attention for the connections we continue to deny. We are invited to think and feel through the world created by Sinners, with a discomfort that must look inward.

For those of us who care about telling stories, Sinners offers an approach that reaches into the interstices of existence in intentional and unintentional ways. When we look into stories with care, what we see, and subsequently tell, surfaces experiences that will again be refracted through the prism of human relation.

What Sinners shows is that at the heart of our fights for representation in film media, even when content is harshly historical, have been cinematic choices that avoid complexity. This complexity is a place where all of us already exist, where we are already represented. Here, the relationship between queerness and Blackness comes into focus, but with the sight that Sinners has gifted us, we can see so much more of the connections that make us more alike than we are different.

What can you do?

Read:

- Boundaries of Blackness: AIDS and the Breakdown of Black Politics by Cathy J. Cohen

- Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics? by Cathy J. Cohen

- Sissies and Lovermen: In defence of Barrington from BBC’s Mr Loverman by Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi

- Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde

Watch:

- Paris is Burning a documentary by Jennie Livingston

- The Sinners Trailer

- POSE