“So it is better to speak remembering we were never meant to survive.”

Audre Lorde

I move through the world with a gnawing curiosity about childhood – about what it means to arrive here without consent yet be tasked with carrying forward life itself. This thought returns to me whenever I see a child, hear a child, or remember myself as a child. We’re all born into a cycle of choicelessness: adults create children, and those children grow up and often do the same. It’s neither morbid nor entirely solemn – it’s almost funny, in a cosmic sense. We’re all participating in this vast, ongoing experiment called life, and rarely do we pause to ask: What are we actually doing? And why?

I wrote this piece because I wanted to centre the experience of the child. So often, we project voicelessness onto children to justify our unwillingness to honour the voices they already carry. This isn’t an accusation – it’s a reflection on the human condition. None of us are exempt. But perhaps if we paid deeper attention to the choices we make on behalf of others, especially children, we might build a world that feels better to live in – for all of us.

The inheritance of impossibility

A child is a microcosm. They hold an entire universe within them, and at the same time, they wield a magnifying power – revealing the fabric of the value systems they’ve been raised on. Because the fabric of a child’s life is never just theirs; it is woven from the cloth of society at large. Its stains remain for generations to come.

And we are all those children. Moving and breathing in accordance with the scripts we were fed from the moment we were born. As adults, we move through the world believing we are making choices – when so often, we are only choosing from the options we’ve been allowed.

Who was any of this built for? These systems of tyranny, of neatly organised binaries, these institutions that dictate how to build a legacy – for whom is this legacy the bedrock of success, of safety, of life? What is living, if not a project of discovering, of asking questions, of tearing down what no longer serves us?

We’ve inherited this impossibility, this problem. A nonsensical mosaic that we have memorised in our bones, wafer-thin and fragile. At any moment, the illusion could shatter. And it should.

What might it mean to imagine parenthood not as assimilation, but as radical worldbuilding? It would mean taking the village seriously. Allowing ourselves to need each other; revisiting Indigenous modes of parenting. Because the nuclear family, as it is presented to us, does not serve our interests – it serves capitalism.

To imagine otherwise would mean choosing to stray from all of that.

And it would also mean giving ourselves permission to imagine beyond scarcity and obedience – to see care, not control, as the foundation of life. To treat parenting not as destiny or obligation, but as one way to expand how we show up for each other.

Not everyone will choose it. Not everyone can. But the mere act of considering it – critically, collectively – reveals a fracture in the architecture of what we’ve been told to desire. That fracture? It’s the beginning of freedom.

Family, inherited and otherwise

Nuclear family structures are presented as an automatically ‘safe’, fool-proof, natural answer. Of course, nuclear families can be all these things. Yet, in many nuclear familial structures, children and women face immense precarity, lack of safety and isolation.

If our family structures don’t prioritise community, then what happens when you find yourself in a crisis? What happens when your immediate family is no longer safe? Who do you turn to when all bridges have been burned? In these cases, they do not speak to the actual needs of a family, especially not when there are children involved.

We all grew up with a very specific image of what a “good life” looked like:

Mum + dad + children = normal, safe, happy.

However, safety is not dependent on the appearance of a good family.

These appearances champion an isolated, individualistic approach to homemaking. These were the silent scripts, baked into school books, sermons, sitcoms, and dinner tables. They weren’t just about who you love – they were about how you love. About what you’re meant to build. And more importantly, why. Stability, success, respectability. A life that looks right, even if it doesn’t feel right.

But that formula is brittle when not held up against a critical light. There is immense tension in telling people to desire a blueprint that doesn’t account for their actual desires, their curiosity, or the sanctity of being encouraged to explore and access their options.

Re-storying: The language of liberation

In Rethinking African Feminisms in the “New” Normal, Sylvia Tamale emphasises that we have to find new solutions to these old problems. African feminists have been deeply involved in the work of worldbuilding, accessing older systems of knowledge to address the recurring problem.

The question “how?” is hot on the tongue. “How do we continue to pursue the project of ‘re-storying’ ourselves and reclaiming our humanity in the 21st century with vigour?”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

There is constant messaging that attempts to sever us from our imaginative, intuitive power as a collective. Our ability to imagine futures of freedom outside of hegemony relies on our conscious commitment to resisting these attempts. The issue is that our language hasn’t stepped up to the challenge of resistance. Sylvia writes that “the majority of 21st-century women’s movements on the continent remain stuck in the last century, dealing with 20th-century challenges.”

Our lexicon has long erupted beyond the point of family planning being a non-issue or simply being a matter of women’s rights. “We need to reconceptualise normalised concepts, such as gender and sexuality, patriarchy, rights, equality, and development that are essentialised and binaried,” Sylvia summarises.

This reconceptualisation demands a reckoning not just with gender, but with kinship itself. Saidiya Hartman’s work on care, kinship, and the afterlives of slavery reminds us that the family (as we know it) is already a deeply racialised, imperial construct. So many of us were born into family structures that were never designed to hold us. Our lineage, by design, has been interrupted – and building new kinship structures is not only urgent but ancestral.

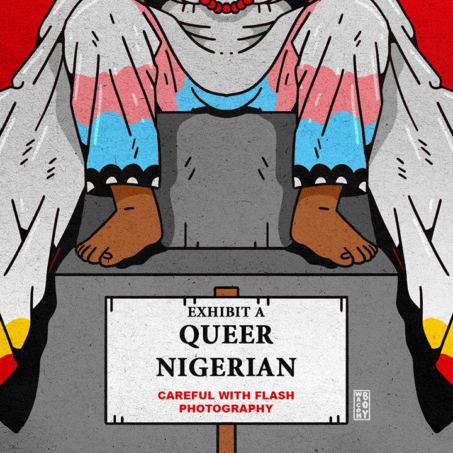

Which is why even imagining non-traditional parenthood becomes an act of refusal. Not because it replicates old models under new branding, but because it disrupts. Because it says: I will build my life outside the blueprint. I will create kin without permission. I will raise new worlds not out of legacy, but out of love. This is the act of queering the family.

To quote bell hooks: “‘Queer’ not as being about who you’re having sex with (that can be a dimension of it); but ‘queer’ as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and that has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.” And to queer family is to queer everything we’ve been taught about what’s possible.

None of this is to sound cynical. I’m not writing from a place of bitterness, but from a deep belief that something else is possible. The reason we need to access better and deeper language is because we can have more. We can do better. We can be better. We are not trapped in these inherited scripts. We are allowed, and in fact called, to rewrite them.

Beyond the nuclear family

Parenting, if it is to mean anything liberatory, must be a community project. There’s no blueprint for a free future that doesn’t centre collective care. The nuclear family, as it’s presented to us, is not just limiting – it is potentially violent in its insistence on isolation. It breeds disconnection, reinforces hierarchies, and keeps all of us – especially the most vulnerable – at the mercy of private struggle. It teaches us to turn inward, to keep secrets, to survive in silence.

An anti-community family model harms everyone. It leaves caregivers unsupported, children unheard, and entire ecosystems of care underdeveloped. It teaches us that love is possession, that protection is control, that vulnerability is weakness. And then it tells us that if we’re exhausted, disconnected, or afraid, the fault is ours – not the architecture we were handed.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. If we’re willing to reimagine the very foundations of family – to invite slowness, multiplicity, and expansiveness into how we raise each other – then parenting can become a site of radical hope. A place where we don’t just reproduce what we know, but grow what we need.

I don’t remember the first time I became aware that the nuclear family was not compulsory. But I do remember the first time I realised that two men could raise children. A neighbour and his husband moved into a house nearby with their adopted kids. It was an astonishing occurrence. So many epiphanies at once: neighbour who is a man has a husband. Two husbands have children. I later learned these children were adopted. I’m sure I knew what adoption was, but it had never occurred to me that this family structure was a possibility too. I tucked this newfound knowledge somewhere deep within the folds of my consciousness and forgot about it, returning to the cold, harsh light of binary thinking.

And so, I went on into the remainder of my childhood, until that same epiphany returned to me in my late teens. As an adult, I think about the quiet salvation of chosen family. Of true and honest community. I think about how many people are lifted up by those they were never taught to call kin. How many lives are held together by love that once felt impossible. And how, even in a world that tries to contain our dreams, something as simple as seeing a different kind of family can split the sky open – just enough for possibility to pour through.

Parenthood as political refusal

In a conversation with a Black lesbian parent, I posed a simple question: How would your life be different had you been raised by a parent like you? There was a long pause. Many of us engage in the quiet, strange work of reparenting ourselves. Many of us do so without naming it as such.

“I think I would be less obsessed with how I’m perceived,” she finally said. “I’d spend more time feeling and less time thinking.”

I asked others too, in passing moments and late-night voice notes. Another friend told me: “I think I’d trust my own body more. I wouldn’t have spent so long thinking it was a problem to solve.”

Another said: “I’d probably still be Christian. Not in the way they taught us, but in a way that felt safe, because I’d never have been told God hated me.”

Someone else paused before saying: “I think I’d be softer. It wouldn’t have to be so hard to survive.”

Each answer landed with devastating clarity. I wanted to offer them something in return: You deserved that. You still do.

I think about what it means that so many people, when asked this question, pause. That silence holds grief, but it also holds possibility. A flicker of imagination. A moment where we glimpse a life that could have been – and perhaps, a life that still could be.

Children as people, not property

Children are an oppressed class, but because we see them as property, they are not protected. Their rights are conditional. Their safety is negotiated through the whims and traumas of adults. We don’t see them as full people – not really. We govern them, discipline them, decorate them, but rarely do we listen. Rarely do we honour their interior worlds.

Children are sovereign human beings with infinite knowledge to share and gain. But we don’t treat them as such. We think of them as interruptions to daily life. Tiny bodies that take up space in inconvenient ways – too loud, too needy, too much. And yet, on the flip side, we fetishise them when they’re cute and can entertain us. We post them, perform them, parade their cleverness for praise. Their value becomes transactional.

It’s no coincidence that so many adults can’t trace their earliest experiences of being respected. We learn early that our worth depends on how easy we are to manage – how little we disrupt the flow of adult life. But what would it mean to raise children outside of obedience? To centre their personhood rather than our projections? To parent with curiosity, not control?

The language of ownership bleeds through every facet of society. I notice it in the way we police each other’s bodies, in how we organise our lives through the lens of respectability and religiosity. I notice it in how we speak about ourselves. Whether we admit it or not, we are fluent in the language of control – because we are living under it. Surveillance, monitoring, policing, fear: these are the tools used to keep us obedient to the project of white supremacy.

This matters in a conversation about parenthood because, truthfully, there is no existing model of parenting that doesn’t – in some way – invite us to reproduce that same logic of control. From the moment children are born, we are taught to indoctrinate them. To train them. To own them.

Stick with me. Of course, children need their parents and communities to guide, protect, and teach them. But where we fail children is in the assumption that they have no say – no authority over what happens to their bodies, who they interact with, or what feels safe and right for them. When we equip children with the tools to advocate for themselves – when we follow their lead and learn how to support their sovereignty – we don’t lose authority. We build trust. We protect them better.

Softness as strategy

What I’m learning is this: imagining queer parenthood isn’t just about the literal act of becoming a parent. It’s about how we choose to show up for the world – how we choose to build kinship, how we choose to love. Whether we raise children or not, queer people have always modelled ways to parent each other – in streets, classrooms, clinics, studios, protests, kitchens. We raise worlds within each other. We create homes out of thin air and tenderness.

Queer parenthood, then, becomes a metaphor and a practice. It asks us to care without possession, to guide without erasure, to protect without control. It demands that we imagine futures rooted in something other than scarcity and fear.

Because ultimately, this is about more than parenting. It’s about who we become when we decide that love is not obedience, but liberation. That family is not an institution, but an invitation. That care is not a duty, but a portal to something freer than what we’ve inherited.

I don’t yet know what parenting will mean to me. But I do know I will keep choosing to build a life where all of us – children and adults alike – can finally breathe. Where survival is not the end goal, but the beginning of something like freedom.

What can you do?

- Read the Parenting Path for access to LGBTQIA+ family resources

- Donate or reach out to The Trevor Project

- Read All About Love by bell hooks to help rethink love beyond possession and control

- Listen toHow to Survive the End of the World

- Read 6 self-love ideas to remember from the late Black feminist, bell hooks