The Ministry of Lesbian Affairs, a play centred around an inclusive choir for queer women who meet each week in a community centre in Dean Street, ran for six weeks at Soho Theatre this summer. The state of that centre – with a leaking roof and no ramp for member Fi, who is disabled – foreshadows the disintegration of the group later in the play.

The award-winning writer behind this play is Iman Qureshi, whose first play, The Funeral Director, won the Papatango Prize in 2018. I spoke to Iman about her work, and in many respects, this felt like a conversation with a kindred spirit. Just like Iman, I too am a writer who is queer, South Asian and Muslim.

Iman has previously spoken about how she felt pigeonholed as the “brown commission.” It’s a familiar story, where writers are expected to write about nothing except their marginalised identities. It can be stifling. I often wonder if this is because writers are so commonly advised to write what they know.

But when you’re an outsider, your identity can feel like all that you know, or at least what you think is worth writing about. The urge to constantly write ourselves into a corner, to be the token and not the currency of the industry, means it’s even harder to break into the media.

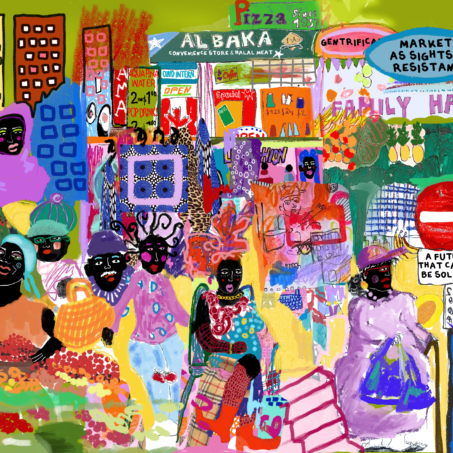

Iman’s play disrupts this narrative by writing not just what she knows but what she knows is important. That’s a clear distinction. Front and centre on stage are the outsiders normally relegated to the sidelines, among them a butch Black lesbian, a trans woman and a closeted queer Muslim woman.

Making your break as a writer

With the lack of opportunities for Black and brown writers in mind, I ask Iman about how she got her start in theatre. “When you’re unrecognised and trying to make it, you just have to throw your work out anywhere that you can,” Iman says. “I was really lucky. There are lots of playwriting prizes. Even getting on the shortlist or longlist is a good exercise in itself, because directors and theatre makers read those entries. They can get to know your names, which can help.”

It’s also a reminder that quality writing is just that: quality, not quantity. “I’m a really slow writer,” Iman explains. “I’m not the sort of writer that has eight plays in a drawer somewhere that I’m just farming out. So if I have one play, I’ll send it to everyone.”

When it came to the first draft of The Ministry of Lesbian Affairs, Iman said it didn’t come easy. Then the director (Hannah Hauer-King) suggested writing entirely unallocated dialogue for the first draft.

“There were no characters in the first draft of The Ministry of Lesbian Affairs,” Iman says, “just voices. It could have been 30 people in a room, or just four. I work like that a lot actually – I’ll just imagine myself in a space and what voices would be there.”

I ask Iman what advice she’d give to writers trying to make their break. “Be ambitious!” she says. “Don’t put yourself in a small box. Don’t think you can only write a one-person show based on your experience. You can write about anything. Write for you – make it a play by you, for you.”

As a fellow writer, this is much-needed advice. So many of the roadblocks that I face when writing or even when planning to write are rooted in worrying what people will think. Is it too divisive? Too political?

Part of it is about the industry – in wanting to break into it and needing to please people to get there. But by Iman I was reminded, as I hope others are, that the first person I need to please is myself.

Why being “out” isn’t always possible

My favourite characters in the play are Lori, a butch Black woman who is a broadband engineer, and Dina, a Qatari Muslim woman who is married with two kids, desperate to explore her sexuality and meet other queer women.

I admit that with Dina, part of it is that we share a name. More than that, though, what drew me to both characters was the fact that they were both in the closet, so to speak, just like me. They both are misunderstood by those around them, just like me.

Lori has been in a relationship with a woman (Ana) for seven years, but she isn’t out to her mother and is reluctant to be affectionate with Ana in public. Ana continues to push her to come out, causing Lori to eventually snap and say that dragging someone out of the closet is racist, and this leads to their relationship breaking down.

Dina is trapped in a marriage to a man, and when the other women ask her why she doesn’t just leave him, she explains that her visa is dependent on her marriage. Without her husband, she would have to go back to Qatar, where LGBTQI+ people are persecuted. And when a video of Dina singing at Pride goes viral for all the wrong reasons, her husband finds out and Dina goes missing.

Her fate is still unknown by the end of the play, but it feels like a cautionary tale, a reminder that coming out can sometimes be unsafe. As a queer Muslim, this spoke to me personally, because the question of coming out in society is usually not if but when, failing to take into account intersectionality and how much being ‘out’ is a privilege.

The play’s reception

I went to see the play a while ago. But I’ll never forget that day because it was the queerest audience I’ve ever been a part of. I didn’t have to look at how many women were holding hands or how many butches I could spot. It was obvious from the way the queer references landed, whether about U-haul lesbians, funny acronyms like OWL (older, wiser lesbian) or sapphic spins on classic lyrics – my favourite being “the lesbians marched in two by two, hurrah, hurrah”.

Iman cites West End show The Inheritance and miniseries It’s a Sin as her inspiration. The focus in both of these productions was the queer men most affected by the AIDs epidemic. When watching The Inheritance, Iman reflects how in the audience, she “saw male couples holding hands and crying on each other’s shoulders,” and she wanted to do this for queer women too.

The play’s run sold out, and with every in-joke and the laughter it elicited, I felt seen as a queer woman. And I wasn’t the only one.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Some reviews seem to object to the change in tone in the final act of the play, which becomes much more serious as the group of queer women become progressively more divided.

But that is the reality, however uncomfortable, for many queer women who are disabled, trans, Black or Muslim. And it was then that I felt not just seen, but heard, loud and clear. Because while our identities are at an intersection, that doesn’t mean different roads are miles away. We should be able to venture into different paths – and when we do, we should feel included and safe.

What can you do?

Donate and find out more about these incredible organisations:

- Hidayah LGBT and Imaan, two Muslim LGBTQ charities in the UK

- ParaPride is a charity for LGBTQ disabled people, and Brownton Abbey focuses specifically on LGBTQ disabled people of colour

- Exist Loudly CIC helps young Black LGBTQ people and the Black Trans Alliance helps Black trans people

- London Playwrights Blog has opportunities for aspiring playwrights

- Read an interview with author Samra Habib HERE

- Read the book, We Have Always Been Here by Samra Habib